In a leafy neighborhood in Dusseldorf, Germany, Milena and Manuel David planned to break ground this summer on a new home, a milestone that was going to get them out of a cramped apartment where they share a bedroom with their two kids.

However, during the 16-month wait for a permit, mortgage rates had tripled and their building costs rose by 85,000 euros (US$90,120). The couple crunched the numbers again before facing the fact that their dream of building their own home had collapsed as part of Europe’s worst construction crisis in decades.

Similar struggles are playing out across much of the continent. Residential building has tumbled as costs soar, while sluggish bureaucracies and increasingly stringent energy-efficiency regulations add to the headwinds. With housing already tight, the situation threatens to weigh on growth and further stoke political tensions as shortages squeeze increasingly more voters.

“I spent so many nights lying awake,” said Milena, a 37-year-old teacher, overlooking the overgrown shrubs and weeds where her kids were supposed to be playing. “What makes me angry is that we were so close.”

The Davids were prime home-building candidates. The family has two incomes, stable jobs in the public sector, and most importantly, they did not have to pay for their building lot, which was given to them by Manuel’s parents. Their struggles show just how broken Europe’s housing market is.

“If we’re given this massive leg up and we’re still struggling, how are others supposed to make it at all,” said Manuel, a 35-year-old project manager at a non-profit organization.

The hardest-hit countries are among the wealthiest. New building permits in Germany fell more than 27 percent in the first half of the year. Permits in France were down 28 percent through July, and UK home building is expected to drop more than 25 percent this year. Sweden is suffering its worst slump since a crisis in the 1990s, with building rates less than a third of what is considered necessary to keep up with demand.

The downturn is affecting single-family homes — like the one the Davids were planning — as well as large housing projects. Vonovia SE, Germany’s biggest landlord, this year shelved all new construction indefinitely. In Sweden, a key project to make battery cells for cars and reduce the region’s dependence on supply from China, risks struggling to attract enough workers because of a lack of housing.

The situation means governments are falling short on promises to voters. Sweden has a constitutional pledge to provide affordable housing, but supply of rental apartments has not kept up with demand for decades, driving up home prices and forcing people to live in black-market sublets. In the UK, home building has consistently missed a target of 300,000 houses per year set by the ruling Conservative government in 2019.

In Germany, affordable housing was one of the key commitments made by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s ruling coalition when it took power in 2021, but economists estimate that the government will not reach its goal of adding 400,000 new homes annually until 2026 at the earliest.

“Making sure citizens have a place to live is one of the state’s most essential duties,” said Kolja Muller, co-head of the Scholz’s Social Democratic Party in Frankfurt. “It’s clearly failing.”

The squeeze on housing risks widening social divides by forcing people to shell out more of their income for accommodation. Attitudes toward migrants could also further deteriorate as they are increasingly seen as rivals for scarce living space. In Lorrach — a town in southern Germany — several dozen tenants were forced to move apartments earlier this year to make way for refugees.

“If we can’t solve the housing crisis, it’ll be a real threat for our democracy,” said Muller, who attributes the rise of the far-right Alternative for Germany — the second-strongest party in polls — in part to tensions over housing.

Trends are not dire everywhere. In Portugal and Spain, housing starts are well above levels in 2015, when the aftermath of the debt crisis all but froze building in those markets, but there are still severe shortages, showing how difficult the problem is to fix.

The struggles to build enough affordable homes ultimately stems from poor government policy. Housing falls somewhere between a market-driven asset and a regulated public good. That combination bogs down investment while subjecting the sector to volatility, and the current upheaval in financing and construction costs often makes building unprofitable, except for luxury homes.

The Burmese junta has said that detained former leader Aung San Suu Kyi is “in good health,” a day after her son said he has received little information about the 80-year-old’s condition and fears she could die without him knowing. In an interview in Tokyo earlier this week, Kim Aris said he had not heard from his mother in years and believes she is being held incommunicado in the capital, Naypyidaw. Aung San Suu Kyi, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was detained after a 2021 military coup that ousted her elected civilian government and sparked a civil war. She is serving a

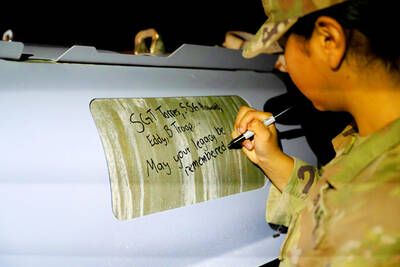

REVENGE: Trump said he had the support of the Syrian government for the strikes, which took place in response to an Islamic State attack on US soldiers last week The US launched large-scale airstrikes on more than 70 targets across Syria, the Pentagon said on Friday, fulfilling US President Donald Trump’s vow to strike back after the killing of two US soldiers. “This is not the beginning of a war — it is a declaration of vengeance,” US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth wrote on social media. “Today, we hunted and we killed our enemies. Lots of them. And we will continue.” The US Central Command said that fighter jets, attack helicopters and artillery targeted ISIS infrastructure and weapon sites. “All terrorists who are evil enough to attack Americans are hereby warned

Seven wild Asiatic elephants were killed and a calf was injured when a high-speed passenger train collided with a herd crossing the tracks in India’s northeastern state of Assam early yesterday, local authorities said. The train driver spotted the herd of about 100 elephants and used the emergency brakes, but the train still hit some of the animals, Indian Railways spokesman Kapinjal Kishore Sharma told reporters. Five train coaches and the engine derailed following the impact, but there were no human casualties, Sharma said. Veterinarians carried out autopsies on the dead elephants, which were to be buried later in the day. The accident site

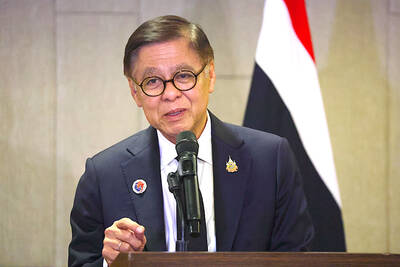

RUSHED: The US pushed for the October deal to be ready for a ceremony with Trump, but sometimes it takes time to create an agreement that can hold, a Thai official said Defense officials from Thailand and Cambodia are to meet tomorrow to discuss the possibility of resuming a ceasefire between the two countries, Thailand’s top diplomat said yesterday, as border fighting entered a third week. A ceasefire agreement in October was rushed to ensure it could be witnessed by US President Donald Trump and lacked sufficient details to ensure the deal to end the armed conflict would hold, Thai Minister of Foreign Affairs Sihasak Phuangketkeow said after an ASEAN foreign ministers’ meeting in Kuala Lumpur. The two countries agreed to hold talks using their General Border Committee, an established bilateral mechanism, with Thailand