Temperatures are rising in Japan and summer is coming fast.

Cherry blossoms are blooming sooner than ever before, chiffon-pink that traditionally heralded spring for the nation, popping up just two weeks into March.

In Osaka, temperatures soared to 25°C on March 22, a record for that time of year. Tottori, in the southwest, hit 25.8°C on the same day, the highest in 140 years, climatologist Maximiliano Herrera said.

Photo: AP

Tottori’s temperatures usually hover at about 12°C in March.

With thermometers already shooting upward and fossil fuel use that feeds climate change still creeping up around the world, Japan is set for another sweltering summer and is at growing risk of flooding and landslides.

The nation is scrambling to protect communities from warming and has pledged to slash emissions, but in the short term the worsening weather remains a threat.

“The risks from climate change are right before us,” said Yasuaki Hijioka, deputy director of the Center for Climate Change Adaptation at the National Institute for Environmental Studies in Tsukubao.

“You can in principle try escaping from a flood. But heat affects such a wide area, there is almost no escape. Everyone is affected,” he said.

Japan is already prone to natural disasters like earthquakes, tsunamis and typhoons. Secure infrastructure has kept people safe for the most part — but climate change means communities are often caught off guard, because the systems were engineered for the weather conditions of the past.

“If you’re pushing the electrical grid that was designed for the 20th century into a new century of warming and heat extremes, then you are going to have to consider whether your energy system and your healthcare system are really designed for a warming planet,” Institute at Brown for Environment and Society director Kim Cobb said.

More people are getting sick because of heatstroke.

Last year, more than 200 temperature records were broken in cities across the nation, sending energy grid to near-capacity and more than 71,000 people to hospital for heatstroke through the months of May to September. Patients were mostly elderly, but a fair number of children and middle-aged adults were also hospitalized, government figures showed. Eighty people died.

The warming weather can also hold more moisture, adding flooding and landslides to the summer forecast, something that Japan has also seen with growing frequency.

In 2019, bullet trains were partially submerged in flooding from Typhoon Hagibis. Homes and highways were caught in landslides. Flooded tunnels trapped people and cars. Dams could not withstand the surprisingly heavy rainfall.

Hijioka’s research is focused on flood management, such as diverting water from swelling rivers upstream into rice paddies and ponds to drain to avert flooding.

To prevent deaths from heatstroke, a proposed law would designate certain buildings in communities, such as air-conditioned libraries, as shelters.

Despite the nation’s advanced economy, some people cannot afford air-conditioning, especially in areas not accustomed to the heat. Schools in northern Japan, such as in Nagano, have installed air-conditioning because of the extreme heat in recent years.

“More people have been dying from heatstroke than from river flooding in Japan,” Hijioka said. “We need to view climate change as a natural disaster.”

Michio Kawamiya, director of the Research Center for Environmental Modeling and Application, and his team research Japan’s higher temperatures and how they affect people.

Among their findings: Since 1953, cherry blossoms have bloomed on average one day sooner every decade. Maple leaves have changed color 2.8 days slower per decade. The risk of typhoons has gone up and the amount of snowfall has declined, even as the threat of heavy snowfall remains.

Japan has made some headway in curbing the amount of fossil fuels it spews, but it is still the world’s sixth-highest emitter. After the 2011 Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant disaster, the nation shut down nuclear generation, and, fatefully for the climate, invested in new coal plants, as well as imported oil and gas, to keep its grid running. Nuclear plants have gradually restarted since then.

On the positive side, its excellent public mass-transit transportation has kept gas-guzzling vehicles off roads, lowering the nation’s carbon footprint. Some Japanese people have been turning their air-conditioning off to save energy, but that has health implications, as it comes precisely at a time when heat has been reaching dangerously high levels.

Japan has already worked so hard to conserve energy by reducing demand that doing more has often been compared to “wringing water out of a totally dry rag,” Kawamiya said in an interview at his office in Yokohama.

Still, critics say Japan could do more to boost renewable energy use, such as solar and wind power. The government plans for renewables to make up more than one-third of the nation’s power supply by 2030 and to phase out coal use sometime in the 2040s.

Japan is also part of the G7 economies that pledged to be largely free of fossil fuels for electricity by 2035.

Since Fukushima, Japan has kept most of the nation’s 50-some nuclear reactors offline, in response to public opinion that has turned against the technology. Nuclear power is considered a clean energy as it does not emit greenhouse gases, but it does produce radioactive waste.

About 10 reactors are up and running, 24 reactors are being decommissioned. What Japan will eventually decide on nuclear power remains unclear.

Hijioka, who believes Japan lags in the shift toward renewable energy, said he was frustrated by policymakers who he said have dragged their feet on dealing with climate change, but are pushing a return to nuclear.

Despite its potential to curb planet-warming emissions, skepticism remains among some climate change experts about turning to nuclear power due to costs and timescales of projects compared with how quickly and cheaply an equivalent amount of renewable energy can come online. There are also concerns among the public.

“It’s utterly irresponsible, when we think about the next generation,” Hijioka said. “We may be old, and we may die so it might not matter. But what about our children?”

Indonesia yesterday began enforcing its newly ratified penal code, replacing a Dutch-era criminal law that had governed the country for more than 80 years and marking a major shift in its legal landscape. Since proclaiming independence in 1945, the Southeast Asian country had continued to operate under a colonial framework widely criticized as outdated and misaligned with Indonesia’s social values. Efforts to revise the code stalled for decades as lawmakers debated how to balance human rights, religious norms and local traditions in the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation. The 345-page Indonesian Penal Code, known as the KUHP, was passed in 2022. It

‘DISRESPECTFUL’: Katie Miller, the wife of Trump’s most influential adviser, drew ire by posting an image of Greenland in the colors of the US flag, captioning it ‘SOON’ US President Donald Trump on Sunday doubled down on his claim that Greenland should become part of the US, despite calls by the Danish prime minister to stop “threatening” the territory. Washington’s military intervention in Venezuela has reignited fears for Greenland, which Trump has repeatedly said he wants to annex, given its strategic location in the arctic. While aboard Air Force One en route to Washington, Trump reiterated the goal. “We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security, and Denmark is not going to be able to do it,” he said in response to a reporter’s question. “We’ll worry about Greenland in

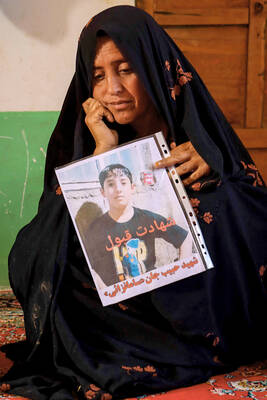

PERILOUS JOURNEY: Over just a matter of days last month, about 1,600 Afghans who were at risk of perishing due to the cold weather were rescued in the mountains Habibullah set off from his home in western Afghanistan determined to find work in Iran, only for the 15-year-old to freeze to death while walking across the mountainous frontier. “He was forced to go, to bring food for the family,” his mother, Mah Jan, said at her mud home in Ghunjan village. “We have no food to eat, we have no clothes to wear. The house in which I live has no electricity, no water. I have no proper window, nothing to burn for heating,” she added, clutching a photograph of her son. Habibullah was one of at least 18 migrants who died

Russia early yesterday bombarded Ukraine, killing two people in the Kyiv region, authorities said on the eve of a diplomatic summit in France. A nationwide siren was issued just after midnight, while Ukraine’s military said air defenses were operating in several places. In the capital, a private medical facility caught fire as a result of the Russian strikes, killing one person and wounding three others, the State Emergency Service of Kyiv said. It released images of rescuers removing people on stretchers from a gutted building. Another pre-dawn attack on the neighboring city of Fastiv killed one man in his 70s, Kyiv Governor Mykola