With Chinese-owned factories torched and workers hunkered down under martial law, Beijing is being pulled into the ulcerous crisis in Myanmar, an unraveling country it had carefully stitched into its big plans for Asia.

During a visit to Myanmar in January last year, Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) elevated the Southeast Asian neighbor to “country of shared destiny” status, Beijing’s highest diplomatic stripe.

The aim was to nudge Myanmar decisively toward China — and away from the US — and drive through billions of dollars of projects under the Belt and Road Initiative, including an oil and gas pipeline, and an Indian Ocean port.

Photo: AP

Fast-forward one year, and the strategically located country has tipped into bloody chaos after the Burmese military, or Tatmadaw, in a coup took out the civilian government of Burmese State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi.

The democracy movement which has since unfurled accuses China of waving through the generals’ power grab and trading Myanmar’s freedom for its own strategic gain. As Burmese security forces kill protesters — nearly 150 so far — Beijing faces a dilemma: back the men with guns or side with an increasingly anti-China public.

“China doesn’t really care who is in government, but it wants a government that will protect Chinese projects and interests,” said Richard Horsey, an expert on Burmese politics. “This is a military that Beijing doesn’t think can bring stability ... and the more China tries to build a relationship with that regime, the more the public will be put offside.”

That is laden with danger for Chinese interests.

At least 32 Chinese-owned textile factories on Sunday were burned down in several townships of Myanmar’s biggest city of Yangon, causing about US$37 million of damage, Chinese state media reported.

A Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman demanded the immediate protection of “Chinese institutions and personnel.”

On Tuesday, Chinese businesses were closed in the flashpoint areas, leaving workers holed up in a “hostile environment” cloaked by martial law, a representative of a garment factory in Yangon’s Shwepyitar Township said.

“All Chinese staff are staying inside the factory [and] some police have also been stationed there,” the spokesperson said, requesting anonymity.

Ominous commentaries have since seeped out of Chinese media, with one saying that Beijing could be prodded “into taking more drastic action ... if the authorities cannot deliver and the chaos continues.”

Twitter accounts of Myanmar democracy groups allege — without offering clear proof — that the military carried out the factory attacks to justify a crackdown in which dozens of protesters died.

Ripples of anti-China sentiment in Myanmar could become waves across a Southeast Asian region suspicious of China’s reach, influence and penchant for debt-trap diplomacy to get its projects over the line.

“Any broad-based popular uprising against Chinese interests can be contagious and percolate anti-China grievances through Cambodia, Laos and elsewhere,” said Thitinan Pongsudhirak, a political science professor at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok.

“China had figured out this piece [Myanmar] of its geostrategic puzzle,” but now there is “no easy play ahead,” he said.

In Myanmar, public anger at Chinese projects has ended major investments before.

Construction of a US$3.6 billion Myitsone Dam in northern Kachin State was spiked a decade ago after widespread opposition, while the voracious Chinese market for rare wood, jade and rubies is routinely blamed by the public for driving the resource grab inside Myanmar.

However, alongside economic interests, China also craves the legitimacy of global leadership and “can’t turn a blind eye to a dark dictatorship” on its doorstep, Thitinan said.

Beijing enjoys exceptional leverage over Myanmar, but it has so far refused to label the military action a coup.

China is the country’s leading foreign investor and supplies the military with hardware.

Observers say that it also maintains alliances with ethnic militias on the long Myanmar-China border, who have been fighting the army for decades.

China has denied any advance knowledge of the Feb. 1 coup, and its official position so far has been to call for de-escalation, while supporting “all sides” in Myanmar’s post-coup crisis.

On Thursday last week, it signed a UN Security Council statement strongly condemning violence against protesters — a rare act by Beijing, which has previously shielded Myanmar at the UN over alleged genocide against the Rohingya minority.

Still, China remains a potential referee, said Soe Myint Aung, a political analyst from the Yangon Center for Independent Research.

“China can play a direct or indirect mediating role for a negotiated compromise,” he said.

First, it would have to chip back at the anger and suspicion in Myanmar.

Anti-Beijing placards are common at protests, and there are rumors of Chinese military flights, while the Internet grumbles with memes urging a boycott of everything Chinese, from video games to Huawei smartphones and TikTok.

“China babysits the Tatmadaw. It is the backbone of disruption in our country,” one democracy supporter said in Yangon, requesting anonymity. “China has dug up our jade and jewels, taken our oil, and now it wants to cut our country in half with its pipeline.”

‘EYE FOR AN EYE’: Two of the men were shot by a male relative of the victims, whose families turned down the opportunity to offer them amnesty, the Supreme Court said Four men were yesterday publicly executed in Afghanistan, the Supreme Court said, the highest number of executions to be carried out in one day since the Taliban’s return to power. The executions in three separate provinces brought to 10 the number of men publicly put to death since 2021, according to an Agence France-Presse tally. Public executions were common during the Taliban’s first rule from 1996 to 2001, with most of them carried out publicly in sports stadiums. Two men were shot around six or seven times by a male relative of the victims in front of spectators in Qala-i-Naw, the center

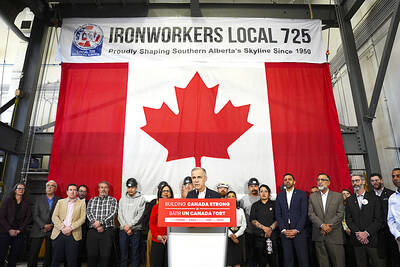

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney is leaning into his banking background as his country fights a trade war with the US, but his financial ties have also made him a target for conspiracy theories. Incorporating tropes familiar to followers of the far-right QAnon movement, conspiratorial social media posts about the Liberal leader have surged ahead of the country’s April 28 election. Posts range from false claims he recited a “satanic chant” at a campaign event to artificial intelligence (AI)-generated images of him in a pool with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. “He’s the ideal person to be targeted here, for sure, due to

Incumbent Ecuadoran President Daniel Noboa on Sunday claimed a runaway victory in the nation’s presidential election, after voters endorsed the young leader’s “iron fist” approach to rampant cartel violence. With more than 90 percent of the votes counted, the National Election Council said Noboa had an unassailable 12-point lead over his leftist rival Luisa Gonzalez. Official results showed Noboa with 56 percent of the vote, against Gonzalez’s 44 percent — a far bigger winning margin than expected after a virtual tie in the first round. Speaking to jubilant supporters in his hometown of Olon, the 37-year-old president claimed a “historic victory.” “A huge hug

DISPUTE: Beijing seeks global support against Trump’s tariffs, but many governments remain hesitant to align, including India, ASEAN countries and Australia China is reaching out to other nations as the US layers on more tariffs, in what appears to be an attempt by Beijing to form a united front to compel Washington to retreat. Days into the effort, it is meeting only partial success from countries unwilling to ally with the main target of US President Donald Trump’s trade war. Facing the cratering of global markets, Trump on Wednesday backed off his tariffs on most nations for 90 days, saying countries were lining up to negotiate more favorable conditions. China has refused to seek talks, saying the US was insincere and that it