Living in a slum built precariously on the banks of a sewage-tainted river in Lebanon, Faiqqa Homsi feels her family being pushed closer and closer to the edge.

A mother of five, she was already struggling, relying on donations to care for a baby daughter with cancer. The coronavirus shutdown cost her husband his meager income driving a school bus.

She hoped to earn some change selling carrot juice after a charity gave her a juicer, but as Lebanon’s currency collapsed, carrots became too expensive.

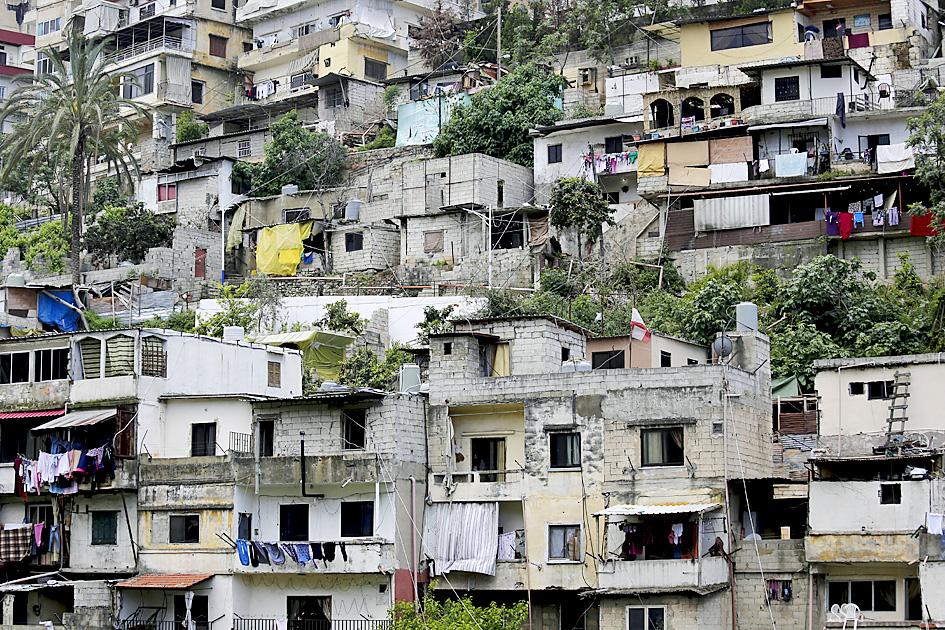

Photo: AP

“It is all closing in our face,” Homsi said.

Lebanese are growing more desperate as jobs disappear and their money’s value evaporates in a terrifying confluence of events. An unprecedented economic crisis, nationwide protests and the COVID-19 pandemic pose the biggest threat to stability since the end of the civil war in 1990, and there are fears of a new slide into violence.

Nowhere is the despair deeper than in Tripoli, Homsi’s hometown and Lebanon’s poorest city. Overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim and home to more than 700,000 people, Tripoli has suffered years of neglect, and is stigmatized with violence and extremism. Mounting poverty is turning it into a powder keg.

Even before the crises, almost the entire city’s workforce depended on day-to-day income, and 60 percent of them made less than US$1 a day.

More than half of the families were in the poorest classification, lacking basic services, education and health care, said Suheir Ghali, a university professor who carried out a study of Tripoli.

Things will get worse as Lebanon’s economy contracts. Already 45 percent of the nation’s population is below the poverty line. The currency has lost nearly 60 percent of its value to the US dollar. Unemployment has risen to 35 percent, nearly double the current US figures rivaling the Great Depression.

Divisions among Lebanon’s sectarian leadership hamper attempts to address the crisis. Hezbollah, which dominates the government, reluctantly supported plans to seek help from the IMF, a sign of its concern about widening hardships. IMF support will likely mean cuts in the public sector, the largest employer, leading to squabbling among political factions. The prime minister, a Sunni, has Hezbollah’s backing, but little within his own sect or in Tripoli.

Tripoli was thrust into the forefront of the anti-government protests that first broke out in October last year. Its boisterous rallies inspired other protesters, who called it the “bride” of the uprising.

Protests returned late last month, more furious and violent, targeting banks. A protester was killed in Tripoli when the army broke up a rally.

“The risk that things might go on a downward spiral [in Tripoli] is real,” said Nasser Yassin, a professor of policy planning at the American University of Beirut.

Tripoli has been the scene of some of Lebanon’s worst violence since the civil war’s end. For weeks in 2007, Islamists battled troops north of the city. The uprising in Syria reignited a bloody rivalry between some of Tripoli’s Sunni and Alawite residents, who belong to the same sect as Syria’s leadership.

Syria’s war — now in its 10th year — stripped Tripoli of its strong trade ties with Syria, a key lifeline. Hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees have moved into Tripoli and surrounding areas.

Residents are also bitter over grand promises that never materialize from rival Sunni politicians vying for their support. Development of Tripoli’s port, a hoped-for gateway for rebuilding post-war Syria, never picked up.

A trade fairground designed by Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer in the 1960s remains abandoned.

At a crafts market project, workshops are shutting down one after the other.

Growing numbers of poor scramble for aid.

Homsi broke into tears when she saw a woman, the age of her mother-in-law, pushed around in a line for food stamps.

Homsi lives in Mulawiya, an illegal favela-like settlement of narrow alleys and ramshackle houses built on top of each other up the steep banks of Abu Ali River. Homsi’s family is crammed into two bedrooms — the kids sleeping in bunk beds next to the kitchen. A large collection of tea and coffee cups — part of her wedding trousseau — is neatly stacked on the kitchen shelves.

Her daughter Maya was diagnosed with cancer as a newborn three years ago. Homsi takes her twice a month to Beirut, a 90-minute bus ride, to a hospital where her treatment is paid for by philanthropists. The little girl has lost half her hair from the chemo and radiotherapy.

Homsi’s eldest son, now 17, dropped out of school to help the family. A fifth of her husband’s US$340-a-month salary went for the trip to Beirut. Now that income is gone.

“I try as best as I can. Sometimes it is at the expense of the other children. It is not because I am harsh, but because there are things I can’t secure,” she said.

Linda Borghol, an activist, started a soup kitchen during the protests. She negotiated to keep it going after the protest camp was broken up.

She now distributes 600 meals a day to the poor.

“We are heading toward a famine. I want to be there, even if with something this small,” she said.

Thousands gathered across New Zealand yesterday to celebrate the signing of the country’s founding document and some called for an end to government policies that critics say erode the rights promised to the indigenous Maori population. As the sun rose on the dawn service at Waitangi where the Treaty of Waitangi was first signed between the British Crown and Maori chiefs in 1840, some community leaders called on the government to honor promises made 185 years ago. The call was repeated at peaceful rallies that drew several hundred people later in the day. “This government is attacking tangata whenua [indigenous people] on all

The administration of US President Donald Trump has appointed to serve as the top public diplomacy official a former speech writer for Trump with a history of doubts over US foreign policy toward Taiwan and inflammatory comments on women and minorities, at one point saying that "competent white men must be in charge." Darren Beattie has been named the acting undersecretary for public diplomacy and public affairs, a senior US Department of State official said, a role that determines the tone of the US' public messaging in the world. Beattie requires US Senate confirmation to serve on a permanent basis. "Thanks to

UNDAUNTED: Panama would not renew an agreement to participate in Beijing’s Belt and Road project, its president said, proposing technical-level talks with the US US Secretary of State Marco Rubio on Sunday threatened action against Panama without immediate changes to reduce Chinese influence on the canal, but the country’s leader insisted he was not afraid of a US invasion and offered talks. On his first trip overseas as the top US diplomat, Rubio took a guided tour of the canal, accompanied by its Panamanian administrator as a South Korean-affiliated oil tanker and Marshall Islands-flagged cargo ship passed through the vital link between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. However, Rubio was said to have had a firmer message in private, telling Panama that US President Donald Trump

‘IMPOSSIBLE’: The authors of the study, which was published in an environment journal, said that the findings appeared grim, but that honesty is necessary for change Holding long-term global warming to 2°C — the fallback target of the Paris climate accord — is now “impossible,” according to a new analysis published by leading scientists. Led by renowned climatologist James Hansen, the paper appears in the journal Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development and concludes that Earth’s climate is more sensitive to rising greenhouse gas emissions than previously thought. Compounding the crisis, Hansen and colleagues argued, is a recent decline in sunlight-blocking aerosol pollution from the shipping industry, which had been mitigating some of the warming. An ambitious climate change scenario outlined by the UN’s climate