Liberty Times (LT): How have you dealt with the controversy over the past few weeks over the screening of the documentary The 10 Conditions of Love?

Cheng Wen-tang (鄭文堂): The question of whether we will be able to show the film at the festival has worried me and made me want to stage a protest. I kept asking myself how I, as a creative artist, should deal with this interference in the freedom of expression. I kept seeing Jean-Luc Godard before my eyes.

LT: Are you referring to 1968? [In 1968, French police suppressed student protests and Godard condemned filmmakers for not being united and for not showing the treatment of workers and students in their work. Godard and Francois Truffaut then launched a protest, demanding that French films and filmmakers withdraw from the Cannes Film Festival.]

PHOTO: CHIEN JUNG-FONG, TAIPEI TIMES

Cheng: That’s right. That kind of sad anger is very similar. Godard stormed up on stage and tore down the film posters and declared that the Cannes Film Festival was over. That is the active mindset of a revolutionary, and it has always been something I respect and admire. Although the Kaohsiung Film Festival is a small event that cannot be compared to Cannes, the emotion is similar. If 10 Conditions was really dropped from the festival, all our efforts to democratize Taiwan over the past 20 years will be undone, and I could no longer be a filmmaker following my own conscience in telling the truth.

LT: What would you do if the film couldn’t be shown at the festival?

Cheng: I’d have walked away.

LT: Would you resign as president?

Cheng: Yes. The whole thing was preposterous. If we were to remove the film because of political interference, we would not only hurt the film, but everyone would be affected. Even a short film, once it’s completed and has been invited [to a festival], should be treated fairly and with respect, everywhere. This may seem politically naive, but from a cultural perspective, this is the attitude we must adopt. I can understand the massive pressure on the [Kaohsiung] city government, but it cannot abandon such fundamental values and beliefs under pressure.

LT: Could you describe these beliefs in more detail?

Cheng: Simply put, it would mean that we will lose our right to creative freedom. The 10 Conditions of Love is simply a biopic about a controversial individual that a documentary filmmaker has spent seven years documenting. On the surface, it would only be a decision to remove it from the festival as a result of political interference, but the practical effect would be that no one will dare challenge taboos. Artists who are worried that they they will not be supported by certain political groups would begin to limit themselves and would not dare to touch topics that they wanted to or should work on. Who would dare follow a more dangerous path? It would be like it was during the censorship era. Who dared make a film about the Kaohsiung Incident or Lei Chen (雷震)? Reality is cruel, and once reality forces artists to become “pragmatic” and they start compromising because they are afraid of or unwilling to do what they should do, what will we be left with?

LT: How was it initially decided to screen The 10 Conditions of Love?

Cheng: I’ve been president of the Kaohsiung Film Festival for five years, and all I want to do is make more people watch movies, create some more movie fans. The premise for a successful festival is that we have good and unique movies and with our limited budget, try to come up with films that would be shown in Kaohsiung for the first time, or a world premiere.

When those who pick the movies decided on 10 Conditions, they only knew that Rebiya Kadeer was a Uighur who the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) didn’t like, and that the film documents her development from an ordinary person to a very wealthy woman who ended up supporting the Uighurs’ opposition to the CCP. The content of the film matches one of the festival’s themes, People Power. We sent out the invitation and both producer and director were happy to approve its showing, which originally would only have been in Kaohsiung, here in Taiwan.

This was before what happened in Melbourne [when China demanded the film be pulled from the Melbourne International Film Festival], so there were no political concerns at all.

LT: So it wasn’t that you wanted to launch a political challenge, but rather that politics found its way to you?

Cheng: Although I have made several documentaries dealing with social issues in the past, I have concentrated on creative works in recent years and haven’t paid much attention to political changes and don’t even watch news on TV. All I can say is that I have moved very far away from politics. Not even after the Melbourne incident did I consider the political repercussions of showing 10 Conditions at the Kaohsiung Film Festival. The city government has complained that I’m not sensitive enough, but 10 Conditions is not about sex, nor does it encourage violence or tell people how to make bombs. It’s simply a documentary. The Kaohsiung Film Festival has been independently run for many years, and my responsibility is only to make sure that the films meet certain standards and are a good watch.

The fact is 10 Conditions is not one of the focal points among the 79 films at this year’s festival. The director isn’t well known. Burma VJ — Reporting From a Closed Country from Myanmar and the biopic about Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara are both stronger and more exciting.

LT: How do you view the concerns of the Kaohsiung tourism industry and the attitude of the Kaohsiung City Government over the controversy?

Cheng: All along I have done what I can to retain the film [in the festival], while also showing my concern for the position of the city government. I hope that everyone will get to hear what the filmmaker wants to say, but the tourism industry must also be heard, and they all deserve both a reaction and respect. The best thing would be if we could achieve both these things, and that’s why I suggested that the film first be given one public showing to let everyone see what kind of film it is and quench their curiosity and put an end to all the wrangling. After the pressure and the media frenzy have died down, we would still have three showings left so the film could be quietly and successfully shown at the festival.

But then the city government decided to move the screening forward and to remove it from the festival. That left us with a strong feeling of defeat, mainly because we would be in a difficult situation if we were unable to protect culture. It wasn’t a matter of the festival losing face, but rather a fear that the value of cultural creativity would be distorted. In the future, no one else would protest, no one would dare oppose those in power or other mighty forces, and they would just choose the path that best meets the interests of those in power. That is a frightening prospect.

LT: What did you do behind the scenes? How did you persuade the city government?

Cheng: From the very beginning, I insisted on approaching the issue from the artist’s perspective. I refused to engage in any protests, and even if every single reporter was trying to get hold of me, I refused to choose the option to put everything on the table. If I also started to run around holding placards or hanging banners, I would at most get a two-page spread in the newspapers, but I would also get caught up in the old Taiwanese political protest culture, and that would not help things.

I chose to ask my friends for help, because the whole issue involved freedom of speech and freedom of creativity. Once a work has been published, others cannot do anything with it, just as you can’t take a piece of art that an artist has painted red and paint it another color, or delete an article published by someone else. This is the universal human right to creativity.

LT: Was the persistence of the Australians of any help to you?

Cheng: The team that made 10 Conditions is very friendly and understand the pressure we’re under. They kept reassuring us and saying we should not let this hurt us, but their ideals were very clear. They didn’t oppose a political party wanting to intervene and show the film across all Taiwan, but they insisted that it must be shown at the film festival, because the invitation from the Kaohsiung Film Festival is the main reason 10 Conditions can be seen in Taiwan at all. The number of screenings can be expanded and it can be shown anywhere on the premise that it is shown at the film festival. If it is, everything else is negotiable. Their insistence is interesting and helpful. If they give up, there’s nothing I can do.

LT: Has this incident aroused your creative desires?

Cheng: I have already started on a documentary about the film festival. I want to explore the question of how the cultural and movie circles approached this issue over the past 10 days. Was there something they thought they should have done? I want to know why Chen Li-kuei (陳麗貴), director of The Burning Mission: Rescue of Political Prisoners in Taiwan (火線任務 — 台灣政治犯救援錄), and Chen Yu-ching (陳育青), director of My Human Rights Journey (我的人權之旅), were the only two directors to withdraw their films from the festival to express their anger over political interference with the festival’s independence.

I don’t want to criticize, I just want to explore why this happened, and what everyone is thinking.

DEFENSE: The National Security Bureau promised to expand communication and intelligence cooperation with global partners and enhance its strategic analytical skills China has not only increased military exercises and “gray zone” tactics against Taiwan this year, but also continues to recruit military personnel for espionage, the National Security Bureau (NSB) said yesterday in a report to the Legislative Yuan. The bureau submitted the report ahead of NSB Director-General Tsai Ming-yen’s (蔡明彥) appearance before the Foreign and National Defense Committee today. Last year, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) conducted “Joint Sword-2024A and B” military exercises targeting Taiwan and carried out 40 combat readiness patrols, the bureau said. In addition, Chinese military aircraft entered Taiwan’s airspace 3,070 times last year, up about

Taiwan is stepping up plans to create self-sufficient supply chains for combat drones and increase foreign orders from the US to counter China’s numerical superiority, a defense official said on Saturday. Commenting on condition of anonymity, the official said the nation’s armed forces are in agreement with US Admiral Samuel Paparo’s assessment that Taiwan’s military must be prepared to turn the nation’s waters into a “hellscape” for the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Paparo, the commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command, reiterated the concept during a Congressional hearing in Washington on Wednesday. He first coined the term in a security conference last

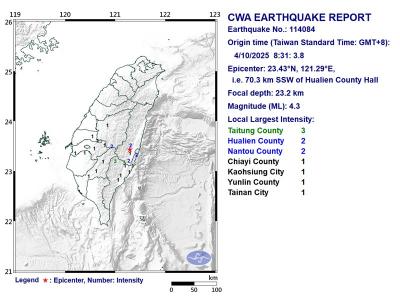

A magnitude 4.3 earthquake struck eastern Taiwan's Hualien County at 8:31am today, according to the Central Weather Administration (CWA). The epicenter of the temblor was located in Hualien County, about 70.3 kilometers south southwest of Hualien County Hall, at a depth of 23.2km, according to the administration. There were no immediate reports of damage resulting from the quake. The earthquake's intensity, which gauges the actual effect of a temblor, was highest in Taitung County, where it measured 3 on Taiwan's 7-tier intensity scale. The quake also measured an intensity of 2 in Hualien and Nantou counties, the CWA said.

The Overseas Community Affairs Council (OCAC) yesterday announced a fundraising campaign to support survivors of the magnitude 7.7 earthquake that struck Myanmar on March 28, with two prayer events scheduled in Taipei and Taichung later this week. “While initial rescue operations have concluded [in Myanmar], many survivors are now facing increasingly difficult living conditions,” OCAC Minister Hsu Chia-ching (徐佳青) told a news conference in Taipei. The fundraising campaign, which runs through May 31, is focused on supporting the reconstruction of damaged overseas compatriot schools, assisting students from Myanmar in Taiwan, and providing essential items, such as drinking water, food and medical supplies,