It’s won Oscars. Its television shows and K-pop stars dominate global charts. Its leading novelist just won the Nobel literature prize. How did South Korea become such a global cultural powerhouse?

What is Hallyu?

From the late 1990s, Korean dramas and K-pop idols started gaining traction in neighboring Asian countries like China and Japan, marking the start of Hallyu, or the Korean Wave.

Photo: EPA-EFE 照片:歐新社

It wasn’t until Psy’s breakout hit “Gangnam Style” that Hallyu hit the West.

In the decade that followed, “Babyshark” broke YouTube records, K-pop megastars BTS topped the charts, Bong Joon-ho’s “Parasite” won an Oscar, and Squid Game became Netflix’s most-watched non-English television show.

Cultural exports were worth some US$13.2 billion to South Korea in 2022, more than home appliances or electric cars — but the bulk of that was made up of video games, such as Battlegrounds Mobile which are wildly popular in India and Pakistan.

Photo: AP 照片:美聯社

The government is targeting US$25 billion by 2027 — so expect more K-culture, especially in new markets such as Europe and the Middle East.

Why South Korea?

For Oscar-winning “Parasite” director Bong Joon-ho, the key to the East Asian country’s cultural success is that everyone has lived through “dramatic times.”

Photo courtesy of Netflix 照片:Netflix 提供

The 1950s Korean War — which left Seoul locked in conflict with its nuclear-armed northern neighbor — military dictatorship, sweeping economic transformation, and a democratic transition.

In the South, many have “experienced turbulence and extreme events,” Bong has said. As a result “our movies can’t help but different.”

South Korea “provides creators with ample inspiration and stimulation. It’s such a dynamic and turbulent place,” he said.

Photo courtesy of Catchplay 照片:Catchplay 提供

Renowned South Korean filmmaker Park Chan-wook had a similar answer when asked for the secret of his country’s cinematic success. “Why don’t you try living in ‘dynamic Korea?’” he replied.

And K-literature?

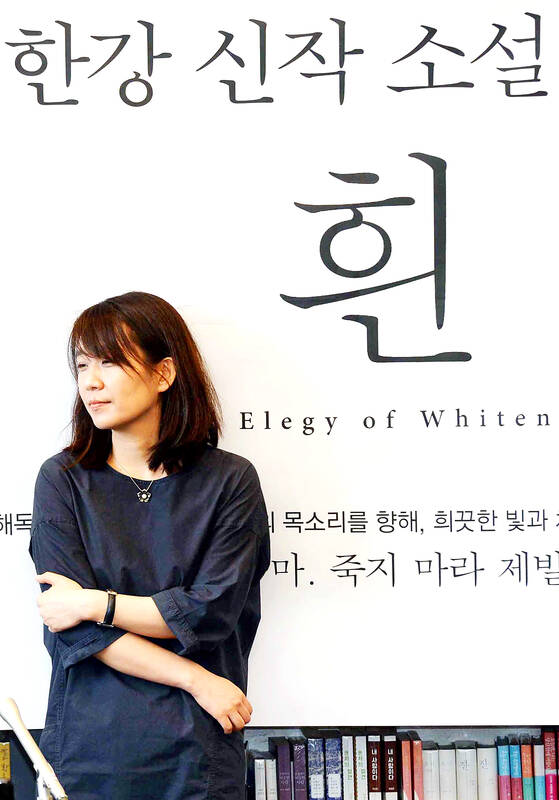

Turning contemporary history into art is what 53-year-old novelist Han Kang, who won the literature Nobel Thursday, excels at.

Han has spoken of the transformative experience of learning about a 1980 massacre in her native Gwangju, when South Korea’s then-military government violently repressed a democratic uprising.

Han said her father showed her photographs including the scattered bodies of victims, and citizens lining up to donate blood in the chaos — which later inspired her book “Human Acts.”

While many South Korean authors have delved into the themes of the country’s traumatic past, Han established her own “striking literary aesthetic” while addressing challenging subjects, said Oh Hyung-yup, a Korean literature professor at Korea University and literary critic.

Women first?

South Korea has some of the worst rates of female workforce participation among advanced economies, but for cultural exports women have been trailblazers.

Han’s Booker-winning novel “The Vegetarian,” which follows a woman who stops eating meat, is regarded as a landmark ecofeminism text. But it was outsold internationally by Cho Nam-Joo’s “Kim Ji-young, Born 1982” about a married South Korean woman who quits her job to raise her child.

As the first Asian woman to win a Nobel for literature, it is appropriate that Han Kang’s work addresses violence in ways that male authors have not in the past, Kang Ji-hee, a South Korean literary critic said.

“Han Kang reinterpreted this type of internal struggle,” Kang said, documenting behaviors “that were previously considered to be simply passive, and gave them a whole new meaning.”

So was it the government?

With the growing success of K-culture exports across the board — from film to food, with Korean staples like kimchi and bibimbap soaring in popularity overseas — it seems like part of a masterplan.

But while the South Korean government has ploughed millions into supporting cultural industries, experts say success has come largely despite, not because, of the state.

When former-president Park Geun-hye was in power from 2013 to 2017, Nobel-winner Han was one of over 9,000 artists “blacklisted” for criticizing her government, along with Bong.

Some government initiatives, for example the government-affiliated Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea), may have paid off, helping to bring works like Han’s to a global audience.

But a growing number of translators, who are more adventurous with their choice of works, have also helped to bring edgier offers to the international market.

Success also breeds more success, cultural export-wise: The reading habits of K-pop megastars have boosted K-literature.

When BTS member Jungkook was seen reading the self-help book “I Decided to Live as Me” it sparked a sales frenzy, with hundreds of thousands of copies flying off shelves.

But Bong also believes that his compatriots’ hard drinking habits helped spur creativity. “We are a very workaholic country. People work too much. And, at the same time, we drink too much. So every night, very hardcore.

(AFP)

他們得過奧斯卡獎,他們的電視節目及流行音樂明星佔據全球排行榜,他們的小說名家甫獲諾貝爾文學獎。南韓是如何成為全球文化強國的?

「韓流」是什麼?

自1990年代末起,韓劇及韓國流行音樂偶像開始在中國和日本等亞洲鄰國受到矚目,標誌「韓流」的緣起。

但直到歌手Psy的爆紅單曲《江南style》,韓流才開始風靡西方。

在接下來十年中,《鯊魚寶寶》打破了YouTube紀錄,流行樂巨星防彈少年團高居排行榜冠軍,奉俊昊的《寄生上流》贏得奧斯卡獎,《魷魚遊戲》成為Netflix收視率最高的非英語電視節目。

2022年,韓國的文化出口額約為132億美元,超過了家用電器或電動車,但其中大部分是電玩遊戲,例如在印度和巴基斯坦廣受歡迎的《絕地求生》手機版。

韓國政府的目標是到2027年投資250億美元,因此韓國文化可見度會更高,尤其是在歐洲和中東等新市場。

為何是韓國?

對於以《寄生上流》獲奧斯卡獎的導演奉俊昊來說,韓國這東亞國家文化成功的關鍵,是每個人都經歷過「戲劇性的時代」。

1950年代的韓戰,讓首爾與擁有核武的北韓陷入衝突,軍事獨裁、經濟全盤轉型,以及民主轉型。

奉俊昊說,在南韓,許多人「經歷過動盪和極端事件」。因此,「我們的電影自然而然與眾不同」。

韓國「為創作者提供了充足的靈感和刺激。這真是個充滿活力和動蕩的地方」,他說。

被問及韓國電影成功的秘訣時,韓國著名導演朴贊郁也給出了類似的答案。「何不在『充滿活力的韓國』住住看呢?」他答道。

還有韓國文學?

將當代歷史轉化為藝術,是10月10日獲諾貝爾文學獎的53歲小說家韓江的拿手好戲。

韓江談到她了解到「光州事件」後,對她的的巨大影響。她的出生地光州1980年發生了大屠殺,一場民主反抗被韓國當時的軍政府血腥鎮壓。

韓江說,她父親給她看了照片,包括散落各處的受害者屍體,以及在動亂中排隊捐血的民眾——這些照片後來讓她寫出了《少年來了》一書。

高麗大學韓國文學教授兼文學評論家吳亨燁表示,雖然許多韓國作家都深入探討了韓國這段傷痛的歷史,但韓江在處理具挑戰性的主題時建立了自己的「特出的文學美學」。

女性是先驅?

在已開發經濟體中,韓國的女性勞動參與率是最低的,但在文化出口方面,女性一直是開拓者。

韓江獲布克獎的小說《素食者》,描寫一位停止吃肉的女性,被認為是具里程碑意義的生態女性主義文本,但它的國際銷量卻不及趙南柱的《82年生的金智英》,這本書講述一位已婚韓國婦女辭去工作撫養孩子的故事。

韓國文學評論家姜智熙表示,韓江作為第一位獲得諾貝爾文學獎的亞洲女性,她的作品以男性作家過去未曾採用過的方式處理暴力問題是恰當的。

「韓江重新詮釋了這種內在掙扎」,姜智熙說,記錄了「過去被認為只是被動的行為,並賦予全新的含義」。

這是政府主導的嗎?

韓國文化出口的全面成功——從電影到食品,泡菜和石鍋拌飯等韓國日常食物在海外受歡迎的程度飆升——讓它看來像是種全盤規劃。

不過,儘管韓國政府投入了數百萬美元來扶植文化產業,但專家表示,它之所以成功,很大程度上是由於對政府影響的逃脫,而非政府的影響。

在南韓前總統朴槿惠2013年至2017年執政期間,諾貝爾獎得主韓江跟奉俊昊一樣,都因批評政府而成為九千多位被列入「黑名單」的藝術家之一。

一些政府作為,例如隸屬於政府的韓國文學翻譯院,或許已見成效,有助於將韓江等作家的作品帶給全球讀者。

但越來越多的譯者在選擇作品時更具冒險精神,也有助於將更前衛的作品推向國際市場。

成功也會帶來更多的成功,從文化出口的角度來看:韓國流行巨星的閱讀習慣推動了韓國文學的發展。

防彈少年團成員柾國閱讀勵志書《閉嘴,我只想做自己》時,引發了銷售狂潮,數十萬本被搶購一空。

但奉俊昊相信,其同胞的酗酒習慣也有助於激發創造力。「我們國家是工作至上,大家做太多工作了,我們同時也喝得太多,所以每晚都有非常激烈的飲酒聚會,一切都非常極端」。

(台北時報林俐凱編譯)

In an effort to fight phone scams, British mobile phone company O2 has introduced Daisy, an AI designed to engage phone con artists in time-wasting conversations. Daisy is portrayed as a kindly British granny, exploiting scammers’ tendency to target the elderly. Her voice, based on a real grandmother’s for authenticity, adds to her credibility in the role. “O2” has distributed several dedicated phone numbers online to direct scammers to Daisy instead of actual customers. When Daisy receives a call, she translates the scammers’ spoken words into text and then responds to them accordingly through a text-to-speech system. Remarkably, Daisy

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Emma had reviewed 41 resumes that morning. While the ATS screened out 288 unqualified, she screened for AI slop. She could spot it a mile away. She muttered AI buzzwords like curses under her breath. “Team player.” “Results-driven.” “Stakeholder alignment.” “Leveraging core competencies.” Each resume reeked of AI modeling: a cemetery of cliches, tombstones of personality. AI wasn’t just changing hiring. It was draining the humanity from it. Then she found it: a plain PDF cover letter. No template. No design flourishes. The first line read: “I once tried to automate my

Every May 1, Hawaii comes alive with Lei Day, a festival celebrating the rich culture and spirit of the islands. Initiated in 1927 by the poet Don Blanding, Lei Day began as a tribute to the Hawaiian custom of making and wearing leis. The idea was quickly adopted and officially recognized as a holiday in 1929, and leis have since become a symbol of local pride and cultural preservation. In Hawaiian culture, leis are more than decorative garlands made from flowers, shells or feathers. For Hawaiians, giving a lei is as natural as saying “aloha.” It shows love and

1. 他走出門,左右看一下,就過了馬路。 ˇ He walked outside, looked left and right, and crossed the road. χ He walked outside and looked left and right, crossed the road. 註︰並列連接詞 and 在這句中連接三個述語。一般的結構是 x, y, and z。x and y and z 是加強語氣的結構,x and y, z 則不可以。 2. 他們知道自己的弱點以及如何趕上其他競爭者。 ˇ They saw where their weak points lay and how they could catch up with the other competitors. χ They saw where their weak points lay and how to catch up with the other competitors. 註:and 一般連接同等成分,結構相等的單詞、片語或子句。誤句中 and 的前面是子句,後面是不定詞片語,不能用 and 連接,必須把不定詞片語改為子句,and 前後的結構才相等。 3. 她坐上計程車,直接到機場。 ˇ She took a cab, which took her straight to the airport. ˇ She took a cab and it took her straight