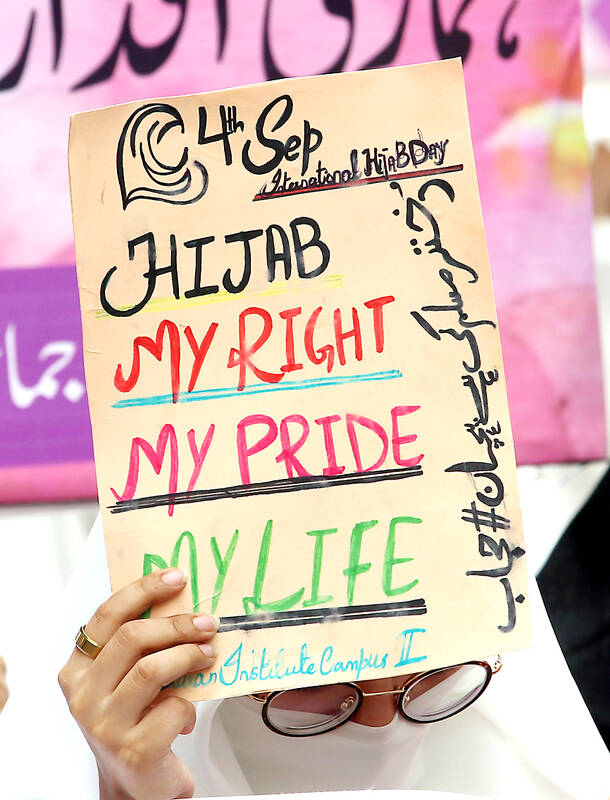

France’s principle of laicite (pronounced lah-eee-see-tay), loosely translated as “secularism,” means no “excessive” crosses, or kippahs, or Islamic head coverings can be worn by staff, students and players in public schools, hospitals, courts and sports fields — though visitors and spectators can.

As the world’s eyes turn to France, host of the Olympics in two weeks, this unique way to define the role of religion in public life is getting more scrutiny.

SECULARISM AS A CONSTITUTIONAL PRINCIPLE

Photo: AP 照片:美聯社

The French Constitution states that “France is an indivisible, lay, democratic and social Republic.”

A 1905 law codifying the separation of church and state, freeing each from the other’s influence, is similar to most other modern democratic states’ that also contended with a violent history of religious conflicts and absolutist regimes.

But the French version, diverging from the multiculturalism approaches next door in the United Kingdom or in the United States, allows the restriction of religious expression in public spaces that provide services to citizens. Such places should be strictly neutral, emphasizing “that which unites more than that which separates,” according to a guide written by the Education Ministry’s council on laicite.

Photo: AFP 照片:法新社

NO SEAT FOR RELIGION IN THE CLASSROOM

The first such space to become legally lay was the school, says Ismail Ferhat, professor at Paris Nanterre University. Laws from the 1880s that made education free and mandatory also required public schools to present no faith viewpoints in the curriculum, and banned pastors from teaching as well as religious symbols in classrooms.

The context for supporters was, and continues to be, that schools should be free of any expression, political or religious or otherwise, that “disturbs the peace.”

Photo: EPA-EFE 照片:歐新社

The first big political clash came in 1989, when three students refused to take off their headscarves in a classroom near Paris and were expelled. The country’s highest administrative court found schools could limit religious symbols that are ostentatious or worn “in a spirit of protest.”

After a surge in incidents, a 2004 law banned wearing anything that “clearly manifests religious belonging” in public schools, though not in universities. Last year, then education minister Gabriel Attal said the ban included abayas and qamis, clothing traditionally worn in Muslim-majority countries — a move criticized by the US government’s Commission on International Religious Freedom.

ANTI-RADICALIZATION OR DISCRIMINATION?

Supporters of this approach say that secularism, especially in schools but also in sports clubs, is crucial for youth to be free from pressures of proselytism and radicalization.

The latter resonates deeply in France, still scarred by the 2015 attacks when Islamist terrorists killed nearly 150 people. Special anti-terrorism measures will be in place for the Olympics, and already heavily armed officers routinely patrol major cities, while signs alerting the public to the threat are posted from amusement parks to theaters.

But critics also see the establishment responding to the rise of anti-immigrant political parties, which fomented the perception of Islam as a danger to the country.

THE BATTLEGROUND OF SPORTS

The battle over secularism extends to sports too, from physical education in schools to elite athletes.

Last year, France’s highest administrative court ruled that the soccer federation can ban headscarves in competitions.

France’s ban on religious symbols for its athletes at the Olympics is in line not only with the country’s secularism and neutrality principles, but with the Olympic charter, said Mederic Chapitaux, an expert on sports and religion who’s also a member of the French government’s council on laicite.

Rule 50.2 of the charter prohibits any “demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda” at Olympic sites — and France is only observing it strictly by not making exceptions, such as for headscarves, he added. Athletes from other countries will observe their own regulations.

But debates over the rule have long simmered and burst onto the global scene in the last Games, amidst renewed concerns for social justice and freedom of expression.

(AP)

法國的「laicite」(發音為lah-eee-see-tay)原則——大致可譯為「世俗主義」——意為公立學校、醫院、法院和運動場的工作人員、學生及運動員不得佩戴「過多」的十字架、基帕〔猶太男性所佩戴的用薄布料或羊毛紡織製成的頭飾,用髮夾固定〕或伊斯蘭頭巾——雖然遊客及觀眾可以。

隨著全世界的目光轉向兩週後將主辦奧運的法國,這種定義宗教在公眾生活中角色的獨特方式正受到更多關注。

作為憲法原則的世俗主義

法國憲法規定:「法國是一個不可分割的、世俗的、民主的、社會的共和國」。

1905年的一項法律規定教會與國家分離,使其免受彼此影響,這與大多數其他現代民主國家的法律類似,這些國家也經歷過宗教衝突與專制政權的血腥歷史。

但法國的做法與鄰國英國或美國的多元文化主義不同,它在為公民提供服務的公共場所限制宗教表達。根據法國教育部世俗主義委員會編寫的一份指南,這些場所應嚴格保持中立,強調這些場所是為了「凝聚而非分裂」人民。

課堂中沒有宗教的位子

巴黎楠泰爾大學〔巴黎第十大學〕教授伊斯麥‧法哈特表示,第一個被法律規定要世俗化的此類場所是學校。1880年代起施行、規定免費義務教育的法律也要求公立學校在課程中不得呈現任何信仰觀點,並禁止牧師教學,以及在課堂上使用宗教符號。

此政策支持者的理由過去是——現在仍然是——學校不該有任何「擾亂和平」的政治或宗教或其他言論。

第一次重大政治衝突發生在1989年,巴黎近郊三名學生拒絕在教室摘下頭巾而被開除。法國最高行政法院裁定,對於「為了抗議」而炫耀或佩戴宗教標誌,學校可以加以限制。

此類事件激增後,2004年頒布了一項法律,禁止在公立學校(但不包括大學)穿著任何「明顯體現宗教歸屬」的服飾。去年,當時的教育部長加布里埃爾‧阿塔爾表示,禁令包括穆斯林女性罩袍及男性卡米斯罩袍,這是穆斯林國家的傳統服裝——此舉遭到美國政府國際宗教自由委員會的批評。

反激進化或歧視?

支持者表示,世俗主義對年輕人擺脫傳教和激進化的壓力至關重要,尤其是在學校和體育俱樂部中。

激進化在法國引起了深刻的共鳴,2015年伊斯蘭恐怖分子造成近150人死亡的攻擊事件,所留下的傷痕至今仍深印法國人心中。奧運期間將採取特別的反恐措施,全副武裝的警察定期在主要城市巡邏,從遊樂園到劇院都張貼告示,提醒民眾注意可疑的人事物。

但批評者也認為,當權者是在回應反移民政黨的崛起,這些政黨煽動了伊斯蘭教對國家構成威脅這種看法。

體育的戰場

有關世俗主義的鬥爭也延伸到了體育領域,從學校的體育課到精英運動員。

去年,法國最高行政法院裁定足球協會可以禁止在比賽中戴頭巾。

體育與宗教專家、法國政府世俗主義委員會成員梅德里克.夏皮托表示,法國禁止運動員在奧運使用宗教標誌不僅符合法國的世俗主義和中立原則,而且符合奧林匹克憲章。

他補充說,奧林匹克憲章第50.2條禁止在奧運場館進行任何「示威或政治、宗教或種族的宣傳」,而法國只是嚴格遵守這一規定,不允許任何例外,例如頭巾。其他國家的運動員將遵守自己的規定。

但圍繞此規則的爭論長期以來一直在醞釀,且在上屆奧運爆發在全球舞台上,人們對社會正義和言論自由再度產生疑慮。

(台北時報林俐凱編譯)

In an effort to fight phone scams, British mobile phone company O2 has introduced Daisy, an AI designed to engage phone con artists in time-wasting conversations. Daisy is portrayed as a kindly British granny, exploiting scammers’ tendency to target the elderly. Her voice, based on a real grandmother’s for authenticity, adds to her credibility in the role. “O2” has distributed several dedicated phone numbers online to direct scammers to Daisy instead of actual customers. When Daisy receives a call, she translates the scammers’ spoken words into text and then responds to them accordingly through a text-to-speech system. Remarkably, Daisy

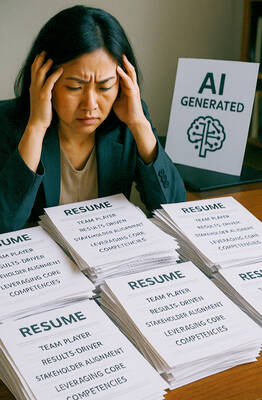

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Emma had reviewed 41 resumes that morning. While the ATS screened out 288 unqualified, she screened for AI slop. She could spot it a mile away. She muttered AI buzzwords like curses under her breath. “Team player.” “Results-driven.” “Stakeholder alignment.” “Leveraging core competencies.” Each resume reeked of AI modeling: a cemetery of cliches, tombstones of personality. AI wasn’t just changing hiring. It was draining the humanity from it. Then she found it: a plain PDF cover letter. No template. No design flourishes. The first line read: “I once tried to automate my

Every May 1, Hawaii comes alive with Lei Day, a festival celebrating the rich culture and spirit of the islands. Initiated in 1927 by the poet Don Blanding, Lei Day began as a tribute to the Hawaiian custom of making and wearing leis. The idea was quickly adopted and officially recognized as a holiday in 1929, and leis have since become a symbol of local pride and cultural preservation. In Hawaiian culture, leis are more than decorative garlands made from flowers, shells or feathers. For Hawaiians, giving a lei is as natural as saying “aloha.” It shows love and

1. 他走出門,左右看一下,就過了馬路。 ˇ He walked outside, looked left and right, and crossed the road. χ He walked outside and looked left and right, crossed the road. 註︰並列連接詞 and 在這句中連接三個述語。一般的結構是 x, y, and z。x and y and z 是加強語氣的結構,x and y, z 則不可以。 2. 他們知道自己的弱點以及如何趕上其他競爭者。 ˇ They saw where their weak points lay and how they could catch up with the other competitors. χ They saw where their weak points lay and how to catch up with the other competitors. 註:and 一般連接同等成分,結構相等的單詞、片語或子句。誤句中 and 的前面是子句,後面是不定詞片語,不能用 and 連接,必須把不定詞片語改為子句,and 前後的結構才相等。 3. 她坐上計程車,直接到機場。 ˇ She took a cab, which took her straight to the airport. ˇ She took a cab and it took her straight