CYCLONE, TYPHOON, HURRICANE — WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

While technically the same phenomenon, these big storms get different names depending on where and how they were formed.

Storms that form over the Atlantic Ocean or central and eastern North Pacific are called “hurricanes” when their wind speeds reach at least 119 kph. Up to that point, they are known as “tropical storms.”

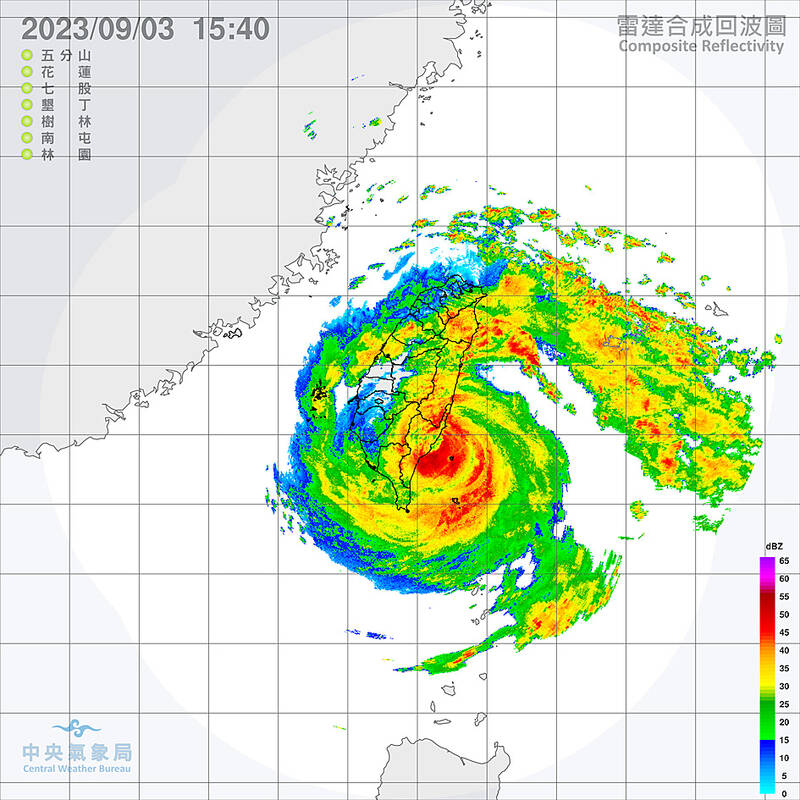

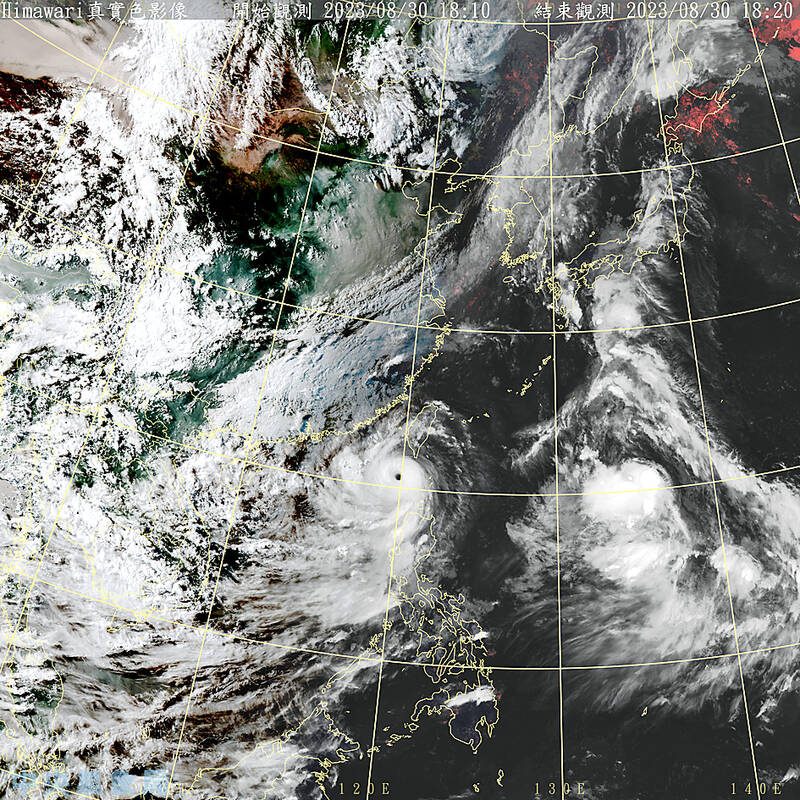

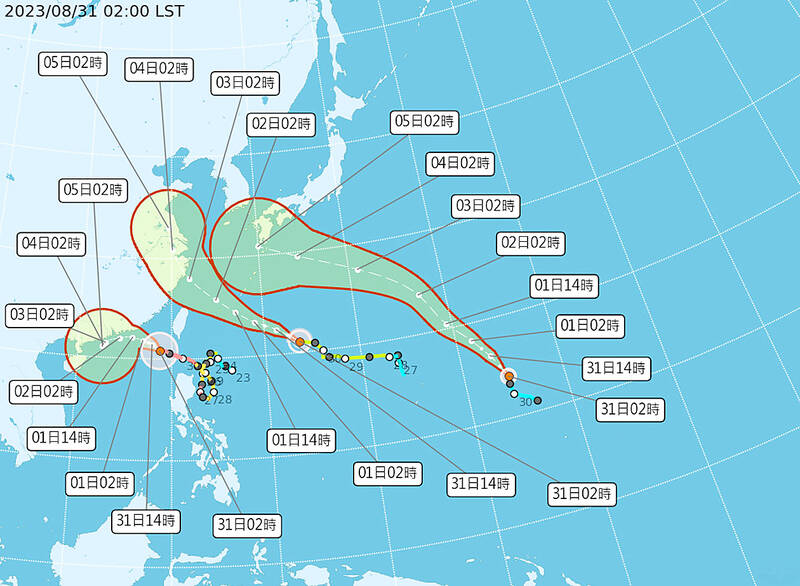

Photo courtesy of Central Weather Bureau 照片:中央氣象局提供

In East Asia, violent, swirling storms that form over the Northwest Pacific are called “typhoons,” while “cyclones” emerge over the Indian Ocean and South Pacific.

HOW DO HURRICANES FORM?

Hurricanes need two main ingredients — warm ocean water and moist, humid air. When warm seawater evaporates, its heat energy is transferred to the atmosphere. This fuels the storm’s winds to strengthen. Without it, hurricanes cannot intensify and will fizzle out.

Photo courtesy of Central Weather Bureau 照片:中央氣象局提供

IS CLIMATE CHANGE AFFECTING HURRICANES?

Yes, climate change is making hurricanes wetter, windier and altogether more intense. There is also evidence that it is causing storms to travel more slowly, meaning they can dump more water in one place. If it were not for the oceans, the planet would be much hotter due to climate change. But in the last 40 years, the ocean has absorbed about 90 percent of the warming caused by heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions. Much of this ocean heat is contained near the water’s surface. This additional heat can fuel a storm’s intensity and power stronger winds. And this year is particularly bad.

Climate change can also boost the amount of rainfall delivered by a storm. Because a warmer atmosphere can also hold more moisture, water vapor builds up until clouds break, sending down heavy rain. During the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season — one of the most active on record — climate change boosted hourly rainfall rates in hurricane-force storms by 8 percent to 11 percent, according to an April 2022 study in the journal Nature Communications.

Photo courtesy of Central Weather Bureau 照片:中央氣象局提供

The world has already warmed 1.1 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial average. Scientists at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) expect that, at 2 degrees Celsius of warming, hurricane wind speeds could increase by up to 10 percent.

NOAA also projects the proportion of hurricanes that reach the most intense levels — Category 4 or 5 — could rise by about 10 percent this century. To date, less than a fifth of storms have reached this intensity since 1851.

HOW ELSE IS CLIMATE CHANGE AFFECTING STORMS?

Photo: Chen Hsien-yi, Liberty Times 照片:自由時報記者陳賢義

The typical “season” for hurricanes is shifting, as climate warming creates conditions conducive to storms in more months of the year. And hurricanes are also making landfall in regions far outside the historic norm. In the US, Florida sees the most hurricanes make landfall, with more than 120 direct hits since 1851, according to NOAA. In recent years, however, some storms are reaching peak intensity and making landfall farther north than in the past — a poleward shift may be related to rising global air and ocean temperatures, scientists said.

This trend is worrying for mid-latitude cities such as New York, Boston, Beijing and Tokyo, where “infrastructure is not prepared” for such storms, said atmospheric scientist Allison Wing at Florida State University.

As for timing, hurricane activity is common for North America from June through November, peaking in September — after a summertime buildup of warm water conditions. However, the first named storms to make US landfall now do so more than three weeks earlier than they did in 1900, nudging the start of the season into May, according to a study published in August in Nature Communications. The same trend appears to be playing out across the world in Asia’s Bay of Bengal, where since 2013 cyclones have been forming earlier than usual — in April and May — ahead of the summer monsoon, according to a November 2021 study in Scientific Reports. It is unclear, however, if climate change is affecting the number of hurricanes that form each year.

(Reuters)

氣旋、颱風、颶風:其區別為何?

雖然這些大風暴嚴格來講是相同的現象,但依其形成的地點與方式,其名稱有所不同。

在大西洋或北太平洋中部及東部形成的風暴,若風速達到至少每小時119公里,便稱為「颶風」,未達此風速則叫「熱帶風暴」。

在東亞,西北太平洋上空形成的劇烈旋轉風暴稱做「颱風」,在印度洋及南太平洋上空出現的,則叫做「氣旋」。

颶風是如何形成的?

颶風需要兩個主要成分——溫暖的海水,以及潮濕的空氣。溫暖的海水蒸發時,其熱能轉移到大氣中,這會讓風暴的風力加劇。少了它,颶風就無法增強,最後就會消失。

氣候變化會影響颶風嗎?

是的,氣候變化正在使颶風變得更多雨、風更強,而更加猛烈。還有證據顯示,氣候變化導致風暴移動的速度變更慢,表示它可以讓同一個地方下更多雨。若沒有海洋,地球會因氣候變化而變得更熱。但在過去40年,海洋吸收了約90%的溫室氣體排放所造成的暖化。大部分海洋中的熱都停留在水面附近。這些額外的熱會加劇風暴的強度,並帶來更強的風。而今年的情況尤其糟。

氣候變化也會增加風暴所帶來的降雨量。由於溫暖的大氣層也能容納更多的水分,因此水蒸氣會積聚起來,直到雲層破裂,降下大雨。根據2022年4月發表在《自然通訊》期刊上的一項研究,在 2020年的大西洋颶風季節(有記錄以來最活躍的颶風季之一)期間,氣候變化使颶風的每小時降雨量增加了8%至11%。

全球氣溫已比工業化前平均溫度高了攝氏1.1度。美國國家海洋暨大氣總署(NOAA)的科學家預測,若氣溫升高攝氏2度,颶風的風速可能會增加10%。

NOAA還預測,本世紀達到最強烈級別(4級或5級)颶風的比例,可能會增加約10%。自1851年至今,達到這種強度的風暴還不到五分之一。

氣候變化對風暴有何影響?

典型的颶風「季節」正在發生變化,因為氣候暖化為更多月份創造了形成風暴的有利條件。颶風登陸的地區也遠超出以往的範圍。據NOAA表示,在美國,佛羅里達州是颶風登陸最多的州,自1851年以來已有逾120次遭颶風直接襲擊。然而科學家表示,近年來,一些風暴達到了強度的巔峰,且登陸位置比過去更靠北——這向南北極方向移動的趨勢,可能跟全球氣溫及海洋溫度的上升有關。

佛羅里達州立大學的大氣科學家艾利森‧溫恩表示,這種趨勢讓紐約、波士頓、北京和東京等中緯度城市的處境堪憂,因為這些城市的「基礎設施沒有為此類風暴做好準備」。

至於時間,北美的颶風活動在6月至11月間很常見,在夏季溫暖海水的條件匯集後,而在9月達到頂峰。然而,根據8月在《自然通訊》發表的一項研究,第一批登陸美國、被命名的風暴,比1900年提前了三個多星期,將颶風季節的起始推前到5月。據2021年11月在《科學報告》期刊發表的一項研究,全球似乎也出現了同樣的趨勢,亞洲的孟加拉灣自2013年以來,氣旋形成的時間比以往早——在4月及5月——比夏季的季風還早開始。然而,尚不清楚氣候變化是否影響每年形成的颶風數量。

(台北時報林俐凱編譯)

In an effort to fight phone scams, British mobile phone company O2 has introduced Daisy, an AI designed to engage phone con artists in time-wasting conversations. Daisy is portrayed as a kindly British granny, exploiting scammers’ tendency to target the elderly. Her voice, based on a real grandmother’s for authenticity, adds to her credibility in the role. “O2” has distributed several dedicated phone numbers online to direct scammers to Daisy instead of actual customers. When Daisy receives a call, she translates the scammers’ spoken words into text and then responds to them accordingly through a text-to-speech system. Remarkably, Daisy

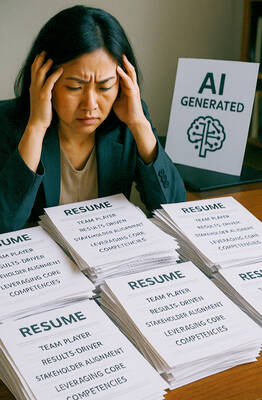

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Emma had reviewed 41 resumes that morning. While the ATS screened out 288 unqualified, she screened for AI slop. She could spot it a mile away. She muttered AI buzzwords like curses under her breath. “Team player.” “Results-driven.” “Stakeholder alignment.” “Leveraging core competencies.” Each resume reeked of AI modeling: a cemetery of cliches, tombstones of personality. AI wasn’t just changing hiring. It was draining the humanity from it. Then she found it: a plain PDF cover letter. No template. No design flourishes. The first line read: “I once tried to automate my

Every May 1, Hawaii comes alive with Lei Day, a festival celebrating the rich culture and spirit of the islands. Initiated in 1927 by the poet Don Blanding, Lei Day began as a tribute to the Hawaiian custom of making and wearing leis. The idea was quickly adopted and officially recognized as a holiday in 1929, and leis have since become a symbol of local pride and cultural preservation. In Hawaiian culture, leis are more than decorative garlands made from flowers, shells or feathers. For Hawaiians, giving a lei is as natural as saying “aloha.” It shows love and

1. 他走出門,左右看一下,就過了馬路。 ˇ He walked outside, looked left and right, and crossed the road. χ He walked outside and looked left and right, crossed the road. 註︰並列連接詞 and 在這句中連接三個述語。一般的結構是 x, y, and z。x and y and z 是加強語氣的結構,x and y, z 則不可以。 2. 他們知道自己的弱點以及如何趕上其他競爭者。 ˇ They saw where their weak points lay and how they could catch up with the other competitors. χ They saw where their weak points lay and how to catch up with the other competitors. 註:and 一般連接同等成分,結構相等的單詞、片語或子句。誤句中 and 的前面是子句,後面是不定詞片語,不能用 and 連接,必須把不定詞片語改為子句,and 前後的結構才相等。 3. 她坐上計程車,直接到機場。 ˇ She took a cab, which took her straight to the airport. ˇ She took a cab and it took her straight