In the words of art critic John Berger, Cubism is the most significant revolution in art since the Renaissance. This is no exaggeration.

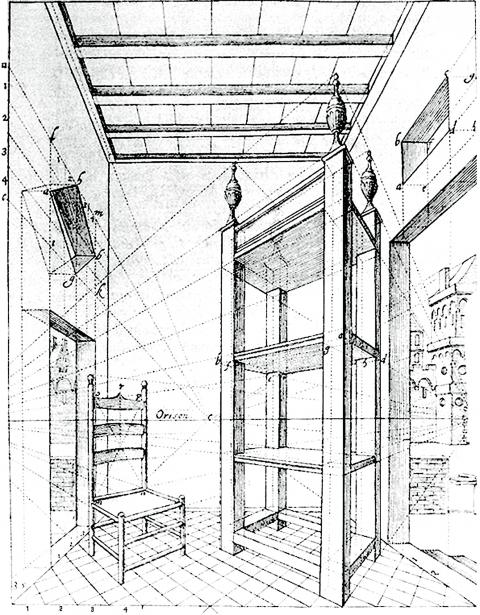

Linear perspective, which matured during the Renaissance and developed with the help of geometry, allowed humans for the first time in history to render precisely what we see with our eyes onto a two-dimensional surface. The trompe-l’oeil illusion can make the depicted as tangible and the space as real as if we could just walk into it.

In this realistic pictorial tradition that has long been taken for granted, paintings like Football Players (photo 1) might seem unimaginable and confusing. (We can start by finding out how many people are depicted in this picture.) In this seemingly chaotic picture by Albert Gleizes (1881-1953), a major figure of the Cubist movement, we can spot a player in blue top running with a rugby football. The player on the left grabs the shoulder of another player, as if trying to block his attack, while another player in the lower left corner falls on the green turf. At the top right of the picture you can see the spectators. Watching the fierce attack and defense in the field, we can almost hear the crowd cheering.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

In a single picture, we can see a series of actions, an exciting game full of twists and turns — and all these are supposed to be unfolded in time.

At the top of the screen, we see houses along a road, a bridge, and something like white clouds or mist on the horizon. These things are supposed to be part of the background, but they are not presented with distance and depth of field that could have been created via linear perspective (photo 2, 3). Instead, the “background” seems to be flattened like a pattern and placed on the same layer as the foreground and subjects.

Football Players demonstrates the mobile perspective and the principle of simultaneity proposed in the On Cubism, written in 1912 by Gleizes and Jean Metzinger (1883-1956). It is not a picture captured in a single moment from a single perspective — like a photograph does — but a combination of different aspects of things in constant movement.

Photos: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

Scrolls, a Chinese painting format, are also good at dealing with sequential time and space. The painting Along the River During the Qingming Festival is a well-known example (see Bilingual Arts on March 25, 2017). Qingming is like a long strip of film that consists of sequential scenes, and the viewer can decide where their gaze lingers. However, Football Players is like a messy pile of film, in which we have no choice but to view scenes from a different time and space at the same time.

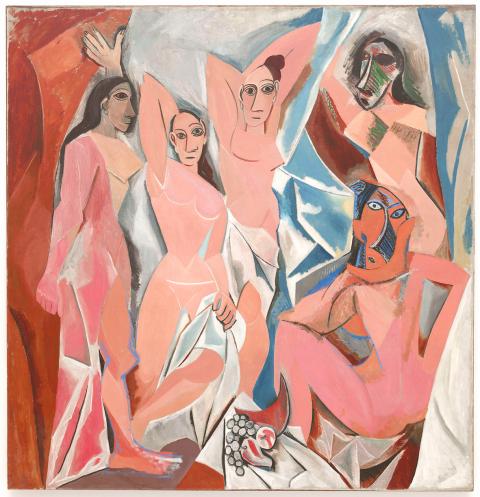

Ever since the proto-cubist Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) (photo 4), by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), and the coining of the term Cubism in 1911, the movement has continued to change the way we see the world.

(Lin Lee-kai, Taipei Times)

Photos: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

藝評家約翰.伯格曾說,立體派是自文藝復興以來最重要的藝術革命。此話並不為過。

文藝復興時期藉助幾何學所發展成熟的線性透視,讓人類首次能夠在平面上建構出如肉眼所見的空間,這種如真的幻覺效果,讓觀者彷彿身在其中。

在線性透視成為理所當然的傳統後,出現了像《足球運動員》【圖一】這樣的畫面,的確令人迷惘。(我們可以先試著找找看,圖中到底有幾個人。)立體派大將格列茲(一八八一~一九五三)這看似紛亂的畫面中,穿藍衣的球員抱著橄欖球奔跑,左方的球員抓著另一人肩膀,似正阻止他進攻,畫面左下角另一球員跌倒在綠色草皮上。畫面右上方則可見到觀眾──隨著場內激烈的攻防,我們彷彿可以聽到場外觀眾的喧騰。

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

在這單單一個畫面,我們可以看到一連串動作、一場扣人心弦的比賽。而這些動作,原本是在時間中展開的。

在畫面上方可見沿路的房屋、一座橋,以及似天邊雲朵的白霧。這些屬於背景的事物,卻失去了原本可藉由線性透視法創造出的景深【圖二、三】,像圖案般平平地貼上畫面,使得背景與前景(人)像是在同一層表面上。

《足球運動員》體現出《立體派宣言》(一九一二年由格列茲與梅金傑所撰寫)所闡釋的移動視角和同時性原則,它所呈現出的,並非如照片般在單一時間、由單一視角所捕捉的畫面,而是事物在不斷運行中不同面向的組合。

「長卷」的中國繪畫形式,也擅於處理連續的時間與空間,《清明上河圖》即為著名的例子(參見二○一七年三月二十五日「雙語藝術」單元)。《清明上河圖》像是拉長的電影膠捲,由一格格景象接續起來,觀者可自行決定在哪一個畫面定格,悠遊其中;但《足球運動員》卻像是亂揉成一堆的底片,強迫我們同時看到不同時空的景象。

自一九○七年畢卡索(一八八一~一九七三)的《亞維儂的姑娘》【圖四】開始,其衍生出的新風格至一九一一年正式名為「立體派」,我們看世界的方式便要開始經歷巨大的改變。

(台北時報林俐凱)

In an effort to fight phone scams, British mobile phone company O2 has introduced Daisy, an AI designed to engage phone con artists in time-wasting conversations. Daisy is portrayed as a kindly British granny, exploiting scammers’ tendency to target the elderly. Her voice, based on a real grandmother’s for authenticity, adds to her credibility in the role. “O2” has distributed several dedicated phone numbers online to direct scammers to Daisy instead of actual customers. When Daisy receives a call, she translates the scammers’ spoken words into text and then responds to them accordingly through a text-to-speech system. Remarkably, Daisy

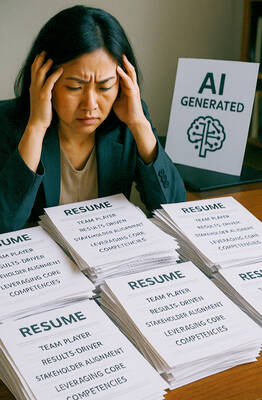

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Emma had reviewed 41 resumes that morning. While the ATS screened out 288 unqualified, she screened for AI slop. She could spot it a mile away. She muttered AI buzzwords like curses under her breath. “Team player.” “Results-driven.” “Stakeholder alignment.” “Leveraging core competencies.” Each resume reeked of AI modeling: a cemetery of cliches, tombstones of personality. AI wasn’t just changing hiring. It was draining the humanity from it. Then she found it: a plain PDF cover letter. No template. No design flourishes. The first line read: “I once tried to automate my

Every May 1, Hawaii comes alive with Lei Day, a festival celebrating the rich culture and spirit of the islands. Initiated in 1927 by the poet Don Blanding, Lei Day began as a tribute to the Hawaiian custom of making and wearing leis. The idea was quickly adopted and officially recognized as a holiday in 1929, and leis have since become a symbol of local pride and cultural preservation. In Hawaiian culture, leis are more than decorative garlands made from flowers, shells or feathers. For Hawaiians, giving a lei is as natural as saying “aloha.” It shows love and

1. 他走出門,左右看一下,就過了馬路。 ˇ He walked outside, looked left and right, and crossed the road. χ He walked outside and looked left and right, crossed the road. 註︰並列連接詞 and 在這句中連接三個述語。一般的結構是 x, y, and z。x and y and z 是加強語氣的結構,x and y, z 則不可以。 2. 他們知道自己的弱點以及如何趕上其他競爭者。 ˇ They saw where their weak points lay and how they could catch up with the other competitors. χ They saw where their weak points lay and how to catch up with the other competitors. 註:and 一般連接同等成分,結構相等的單詞、片語或子句。誤句中 and 的前面是子句,後面是不定詞片語,不能用 and 連接,必須把不定詞片語改為子句,and 前後的結構才相等。 3. 她坐上計程車,直接到機場。 ˇ She took a cab, which took her straight to the airport. ˇ She took a cab and it took her straight