Chinese Practice

信口開河

(xin4 kou3 kai1 he2)

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

foolish or uninformed verbiage

關漢卿(約西元一二四一~一三二O年)是備受推崇的元代劇作家及詩人,被西方人稱為「中國的莎士比亞」。莎士比亞的稱號是「the Bard of Avon」(埃文河畔的的吟遊詩人),關漢卿則號為「己齋叟」。

關漢卿所作的六十五部戲曲,有十四部流傳下來,其中的〈包待制智斬魯齋郎〉,英譯名為「The Wife-Snatcher」(奪人妻者),故事背景是在宋代。故事中的相關人物為魯齋郎(腐敗的高官,因受皇帝寵信,所以沒人治得了他)、李姓銀匠及其妻、小官張孔目及其妻,以及包拯(即包公,史書上有記載的北宋官員,以正直聞名)。

劇中魯齋郎看上了李銀匠的妻子,並把她搶走;李銀匠昏倒在路邊,被張孔目救起,於是兩人成了好友。後來,魯齋郎看到張孔目之妻,被她的美貌所吸引,便強迫張孔目把她送到魯齋郎家中;魯齋郎或許厭倦了先前搶來的李銀匠之妻,便把李銀匠的妻子送給張孔目作為交換。有一天,李銀匠去拜訪張孔目,在張家認出了妻子,於是兩人得以團聚。張孔目看到李氏夫妻團圓的喜悅,對照自己的失意,便把他的財產送給李氏夫妻,然後自己出家去做道士。後來,包拯介入此案,透過計策將魯齋郎繩之以法,把他處決了。在劇中,張孔目在道觀裡對觀眾說了一段獨白,說他絕不會還俗:「你休只管信口開合,絮絮聒聒。俺張孔目怎還肯緣木求魚,魯齋郎他可敢暴虎馮河」(人們別再不停亂說蠢話,還俗就像是爬到樹上去捉魚一樣沒意義,我張孔目是不會做的;魯齋郎想必也不敢鋌而走險,來道觀這裡作亂)。

這句話包含了幾個成語:「暴虎馮河」(徒手打老虎、不藉助浮具渡河,在二O一八年八月六日的「活用成語」中已有說明)、「緣木求魚」(爬到樹上去捕魚,意為徒勞無功,此成語將於下週「活用成語」單元介紹),以及「信口開合」(此語描述嘴巴開合的樣子,意指愚蠢的話,或講話不經思考)。

這段話裡的「信口開合」最後一個字「合」,後來被同音字「河」所取代,變成我們現今所使用的成語「信口開河」,因此其視覺形象由原本嘴巴開合,變成了像河水一樣從口中滔滔不絕地湧出,更強調了無意義的話一連串吐出的樣子。成語「信口開河」現今用來比喻人對其不了解的事隨口亂說。

在英文中,類似的意思可用「full of hot air」表達。如果我們說某人「full of hot air」,意思就是說這人喋喋不休地談論他並不真正理解的事,或並非為真的事。此語的歷史並不特別久遠,出處不詳。有人說「full of hot air」首次出現是在一八七三年的小說《鍍金時代》,此書為馬克‧吐溫和查爾斯‧達德利‧華納所著,書中有此一句:「The most airy schemes inflated the hot air of the capital.」(最虛幻的計畫讓首都的熱氣更加膨脹)。然而,對於這是否真為「full of hot air」的出處,筆者仍然存疑。

(台北時報林俐凱譯)

有些政客信口開河,抹黑對手卻拿不出證據,但還是有很多選民被騙得團團轉。

(Certain politicians spout nonsense, criticizing their opponents with little evidence to back up their claims, but many voters are taken in, regardless.)

他這個人就是這樣,多喝幾杯就信口開河、自吹自擂,所以沒人把他的話當真。

(He’s like that: with a few drinks inside him he starts talking nonsense and making wild claims about himself, so nobody takes what he says seriously.)

英文練習

full of hot air

Guan Hanqing (c. 1241–1320), a highly regarded playwright and poet from the Yuan Dynasty, has been referred to as “the Chinese Shakespeare.” While the latter has been given the sobriquet “the Bard of Avon,” Guan is referred to as jizhaisou, “the old man of the studio.”

Among the 65 plays Guan wrote — and of the 14 that are still extant — is baodai zhi zhi zhan lu zhailang, translated as The Wife-Snatcher in English, and set in the Song Dynasty. For our purposes here, the pertinent characters are Lu Zhailang, a corrupt senior official, essentially untouchable as he was on friendly terms with the emperor; Mr. Li, a silversmith, and his wife; Zhang Kongmu, a minor official and his wife; and Bao Zheng, a historical Northern Song official renowned for his honesty.

In the play, Lu takes a fancy to Li’s wife and snatches her for himself; Li, in shock, collapses by the roadside and Zhang goes to his aid, marking the beginning of a close friendship between the two men. Later, Lu sees Zhang’s wife and, enraptured by her beauty, forces Zhang to send her to him, trading her for Li’s wife, whom he has presumably tired of. One day, Li visits Zhang, and recognizes his wife in Zhang’s home; the two are reunited and Zhang, seeing their joy — and despondent about his own circumstances — leaves his material belongings to the newly reunited couple and goes off to be a Taoist monk. Subsequently, Bao intervenes and engineers Lu’s conviction and eventual execution. In the play, Zhang — in the Taoist temple — delivers a monologue to the audience, explaining that he nevertheless remains unpersuaded it is a good idea to return to society. He says 你休只管信口開合,絮絮聒聒。俺張孔目怎還肯緣木求魚,魯齋郎他可敢暴虎馮河 (Enough of the foolish talk, if you will: returning to my family would be like climbing a tree to catch a fish, and Lu Zhailang would not have been as brazen as to look for me here, anyway.)

That sentence contains several idioms: 暴虎馮河 (tackling tigers unarmed; wading rivers unaided) was described in Using Idioms on Aug. 6, last year; 緣木求魚 (to climb a tree to catch a fish) — meaning “to attempt an impossible or pointless endeavor” — will feature in Using Idioms next week. The phrase 信口開合 — a visual metaphor describing the mouth opening and closing — is used to mean “foolish talk,” or speaking without first thinking something through.

The last character in the phrase 信口開合 was later replaced by the homophone 河 (river), to give us the idiom used today, 信口開河, changing the visual metaphor of a mouth opening and closing to one of a river gushing from the mouth, accentuating the idea of a torrent of nonsensical verbiage. It is used nowadays to suggest that someone is mouthing off about things they are ill-informed about, or unqualified to comment on.

In English, a similar sentiment is captured in the phrase “full of hot air.” If we say somebody is full of hot air, we mean that they are talking about things they don’t really understand, or about things that are not entirely — or even remotely — true. The phrase is not an especially old one, and its origins are unclear. Some say that its first citation is in the 1873 novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, in which appears the phrase “The most airy schemes inflated the hot air of the capital.” As to whether that is actually the origin of the phrase “full of hot air” in any meaningful sense, I remain unpersuaded.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

I wouldn’t listen to his advice, if I were you. He’s full of hot air, and doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

(換做是我,我不會聽他的話。他只是信口開河,根本不知道自己在說什麼。)

In an effort to fight phone scams, British mobile phone company O2 has introduced Daisy, an AI designed to engage phone con artists in time-wasting conversations. Daisy is portrayed as a kindly British granny, exploiting scammers’ tendency to target the elderly. Her voice, based on a real grandmother’s for authenticity, adds to her credibility in the role. “O2” has distributed several dedicated phone numbers online to direct scammers to Daisy instead of actual customers. When Daisy receives a call, she translates the scammers’ spoken words into text and then responds to them accordingly through a text-to-speech system. Remarkably, Daisy

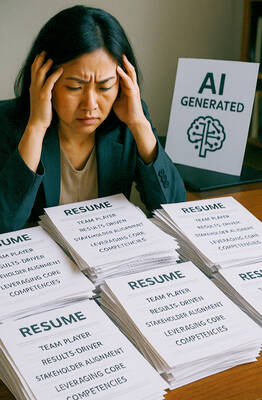

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Emma had reviewed 41 resumes that morning. While the ATS screened out 288 unqualified, she screened for AI slop. She could spot it a mile away. She muttered AI buzzwords like curses under her breath. “Team player.” “Results-driven.” “Stakeholder alignment.” “Leveraging core competencies.” Each resume reeked of AI modeling: a cemetery of cliches, tombstones of personality. AI wasn’t just changing hiring. It was draining the humanity from it. Then she found it: a plain PDF cover letter. No template. No design flourishes. The first line read: “I once tried to automate my

Every May 1, Hawaii comes alive with Lei Day, a festival celebrating the rich culture and spirit of the islands. Initiated in 1927 by the poet Don Blanding, Lei Day began as a tribute to the Hawaiian custom of making and wearing leis. The idea was quickly adopted and officially recognized as a holiday in 1929, and leis have since become a symbol of local pride and cultural preservation. In Hawaiian culture, leis are more than decorative garlands made from flowers, shells or feathers. For Hawaiians, giving a lei is as natural as saying “aloha.” It shows love and

1. 他走出門,左右看一下,就過了馬路。 ˇ He walked outside, looked left and right, and crossed the road. χ He walked outside and looked left and right, crossed the road. 註︰並列連接詞 and 在這句中連接三個述語。一般的結構是 x, y, and z。x and y and z 是加強語氣的結構,x and y, z 則不可以。 2. 他們知道自己的弱點以及如何趕上其他競爭者。 ˇ They saw where their weak points lay and how they could catch up with the other competitors. χ They saw where their weak points lay and how to catch up with the other competitors. 註:and 一般連接同等成分,結構相等的單詞、片語或子句。誤句中 and 的前面是子句,後面是不定詞片語,不能用 and 連接,必須把不定詞片語改為子句,and 前後的結構才相等。 3. 她坐上計程車,直接到機場。 ˇ She took a cab, which took her straight to the airport. ˇ She took a cab and it took her straight