The sight of gaggles of friends, family and colleagues clustered around disposable barbecues by the road side, sweating over glowing coals as the aroma of singed meat permeates the sultry evening air, is a familiar scene to anyone who has experienced the Mid-Autumn Festival in Taiwan. However, the custom of cooking alfresco under the light of the full moon isn’t as old as one might suppose; rather it is a prime example of the power of advertising.

The practice of barbecuing during Mid-Autumn Festival actually dates back no more than three decades, when two of Taiwan’s largest soy sauce manufacturers, Wan Ja Shan Food and Kimlan Food, jousted with each other in an advertising war to sell their respective barbecue sauce brands.

In 1986, Wajashan Food released a television commercial for its Wan Ja Shan Barbecue Sauce in the run-up to the Mid-Autumn Festival. It included the slogan: “When one household grills on the barbecue, ten thousand families smell the aroma.” The commercial featured sizzling-hot celebrity of the moment, Chang Yung-yung, as the condiment’s brand ambassador, helping ignite the craze for Mid-Autumn Festival barbecuing.

Photo: Fang Pin-chao, Taipei Times

照片:自由時報方賓照

Three years later Kimlan Food released its own television commercial as part of a saturation advertising campaign for its rival Bar-B-Q Sauce. The advertisement featured footage of food being liberally doused with barbecue sauce to an infectiously catchy jingle. Not to be outdone, Wajashan Food launched a counter-offensive, releasing an updated version of its original hit television commercial.

Around the same time, new supermarkets and wholesalers such as Wellcome, Carrefour and the now obsolete Makro began to offer discounts on barbecue food ingredients and accoutrements in the lead-up to the festival. The combined effect of these commercial campaigns gradually led to barbecuing being associated with the Mid-Autumn Festival in the minds of the Taiwanese public. Char-grilling everything under the sun — from Chinese sausages, pig’s blood cake and Taiwanese-style tempura — is now so popular that it has become the number one activity associated with the festival in Taiwan.

By contrast — similar to Taiwan prior to the mid-1980s — in China the Mid-Autumn Festival is still largely celebrated in accordance with its harvest festival origins. Families come together to celebrate the legend of Chang E, the Chinese goddess of the moon, by watching the full moon appear in the nighttime sky and feasting on moon cakes: small round sweet pastries traditionally filled with red bean or lotus seed paste and salted egg yolk.

Photo: Screen grab from Youtube

照片:截圖自Youtube

In Taiwan, while the “grill-industry” now rules the roost during Mid-Autumn Festival, sales of moon cakes and seasonal pomelos (the fruit is eaten while the carefully-preserved emerald green peel is worn as a novelty hat) are still big business over the holiday period. Whether one views the modern barbecue craze as a positive evolution of the festival into a unique Taiwanese celebration, or an ancient festival hijacked by corporations and clever marketing, is a matter for debate. One thing is certain though, it is a salutary lesson in the power of advertising to, for better or worse, influence not just consumer behavior, but even alter the mores and traditions of an entire society.

(Edward Jones, Taipei Times)

在台灣體驗過中秋節的人,一定會對以下的景象感到熟悉:朋友、家人以及同事間的談笑聲,眾人圍著路邊架起的拋棄式烤肉架,在燒紅的炭火旁揮汗如雨,微微烤焦的肉香味瀰漫在悶熱的夜晚空氣中。不過,在滿月光芒下露天烹煮食物的這個習俗,其實沒有我們以為的那麼古老,倒不如說,這是廣告力量的最佳範例。

Photo: Lin Shu-chuan, Taipei Times

照片:自由時報

在中秋節期間烤肉的習慣,認真追溯起來,其實並不會超過三十年。當時,台灣最大的兩家醬油製造業者──萬家香食品和金蘭食品──為了促銷各自的烤肉醬品牌,在一場廣告大戰中互別苗頭。

一九八六年,萬家香食品趕在中秋節前,為自家的萬家香烤肉醬推出一支電視廣告,並加入「一家烤肉、萬家香」的標語。這支廣告由當時的電視劇當紅炸子雞張詠詠參與,並擔任該調味醬的品牌大使,就此點燃了中秋節烤肉的熊熊火苗。

三年後,金蘭食品則推出另一支電視廣告,用轟炸式廣告宣傳的手法,促銷自家公司的競爭商品金蘭烤肉醬。這支廣告影片奔放地在食材上刷上厚厚的烤肉醬,再搭配一段極具傳染力又讓人朗朗上口的廣告歌曲。輸人不輸陣,萬家香發動反擊,將最初那支廣受歡迎的電視廣告更新後再度播出。

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

大概在同一時間,當時新興起的超級市場與量販業者──包括頂好、家樂福,以及現已消失在市場上的萬客隆──都開始在中秋節前幾天對烤肉食材和相關用品推出促銷折扣。這些商業促銷活動的加乘效應遂逐漸讓烤肉在台灣人的心目中和中秋節產生聯想。從香腸到豬血糕、台式甜不辣,把天底下所有能吃的東西都拿來炭烤,廣受歡迎的程度大到烤肉在台灣已經成為每次提到中秋節時,第一個被聯想到的活動。

相較之下,中國和一九八○年代中期以前的台灣較為相似,慶祝中秋節的方式仍然主要和該節日慶祝豐收的起源有關,例如祭拜中國的月亮女神嫦娥、與全家人團聚,欣賞夜空中的滿月、以及大快朵頤吃月餅──這類小而圓的甜酥皮點心,傳統上都會填充紅豆沙或蓮蓉餡,再包進一顆蛋黃。

在台灣,雖然「烤肉產業」今日在中秋節慶祝活動中佔據主導地位,月餅和當季盛產的柚子(果肉吃下肚,而小心翼翼完整剝下的翡翠綠果皮可以逗趣地戴在頭上)在假期間仍然是很大的商機。無論將現代的烤肉瘋看成該節日正向地演化成為一種獨特的台灣慶祝活動,還是認為這個古老節日遭到大公司和機巧的行銷手法把持,兩者都是可以爭論的話題。不過,有一件事倒是無庸置疑,那就是中秋節烤肉呈現出一個頗有助益的課題,值得探討廣告的力量是如何──正面或負面地──不僅影響了消費者行為,甚至還改變整個社會的習俗與傳統。

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

(台北時報章厚明譯)

Follow up讀後練習

The commercialization of annual festivals in Western countries

A similar phenomenon to the commercial influence over how the Mid-Autumn Festival is celebrated in Taiwan has occurred in many Western and European countries. The main Christian festivals of Christmas and Easter, for example, have become increasingly commercialized in recent years. During Easter, hand-painted eggs, symbolic of new life, rebirth and the resurrection of Christ, have given way to mountains of mass-produced chocolate eggs, skillfully marketed by the big confectionary manufacturers. The baking at home of a simnel cake, topped with 11 marzipan balls to represent the 12 apostles, minus Judas, is another Easter tradition in the UK and Ireland, now seldom observed.

Christmas has also gradually drifted away from its Christian roots — although it was originally the pagan winter solstice festival of Yuletide before being co-pted by Christianity for itself — toward a retail bonanza of ever-greater food and drink consumption and present buying. As a result, the festive shopping season has become a time of bumper profits for the retail industry, especially in the US, UK and other Anglosphere countries, with many retailers heavily discounting products to entice shoppers through their doors.

(Edward Jones, Taipei Times)

In an effort to fight phone scams, British mobile phone company O2 has introduced Daisy, an AI designed to engage phone con artists in time-wasting conversations. Daisy is portrayed as a kindly British granny, exploiting scammers’ tendency to target the elderly. Her voice, based on a real grandmother’s for authenticity, adds to her credibility in the role. “O2” has distributed several dedicated phone numbers online to direct scammers to Daisy instead of actual customers. When Daisy receives a call, she translates the scammers’ spoken words into text and then responds to them accordingly through a text-to-speech system. Remarkably, Daisy

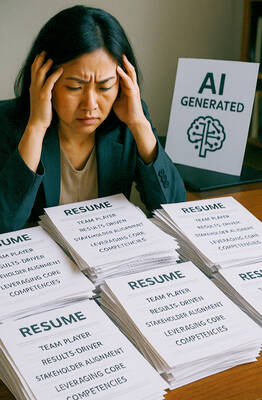

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Emma had reviewed 41 resumes that morning. While the ATS screened out 288 unqualified, she screened for AI slop. She could spot it a mile away. She muttered AI buzzwords like curses under her breath. “Team player.” “Results-driven.” “Stakeholder alignment.” “Leveraging core competencies.” Each resume reeked of AI modeling: a cemetery of cliches, tombstones of personality. AI wasn’t just changing hiring. It was draining the humanity from it. Then she found it: a plain PDF cover letter. No template. No design flourishes. The first line read: “I once tried to automate my

Every May 1, Hawaii comes alive with Lei Day, a festival celebrating the rich culture and spirit of the islands. Initiated in 1927 by the poet Don Blanding, Lei Day began as a tribute to the Hawaiian custom of making and wearing leis. The idea was quickly adopted and officially recognized as a holiday in 1929, and leis have since become a symbol of local pride and cultural preservation. In Hawaiian culture, leis are more than decorative garlands made from flowers, shells or feathers. For Hawaiians, giving a lei is as natural as saying “aloha.” It shows love and

1. 他走出門,左右看一下,就過了馬路。 ˇ He walked outside, looked left and right, and crossed the road. χ He walked outside and looked left and right, crossed the road. 註︰並列連接詞 and 在這句中連接三個述語。一般的結構是 x, y, and z。x and y and z 是加強語氣的結構,x and y, z 則不可以。 2. 他們知道自己的弱點以及如何趕上其他競爭者。 ˇ They saw where their weak points lay and how they could catch up with the other competitors. χ They saw where their weak points lay and how to catch up with the other competitors. 註:and 一般連接同等成分,結構相等的單詞、片語或子句。誤句中 and 的前面是子句,後面是不定詞片語,不能用 and 連接,必須把不定詞片語改為子句,and 前後的結構才相等。 3. 她坐上計程車,直接到機場。 ˇ She took a cab, which took her straight to the airport. ˇ She took a cab and it took her straight