Chinese practice

既往不咎

(ji4 wang3 bu2 jiu4)

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

to forget and not bear recriminations

英文形容詞「bygone」是由一個過去分詞(gone)和一個介詞(by)所組成的,如同「aforesaid」的構字一樣。「aforesaid」(前述)意為「先前已談到的」,「bygone」意為「已經過去的」。雖然「bygone」一字現已很少用,但仍見於「bygone days」(過去的日子)或「a bygone era」(過去的時代)等片語中。

「bygone」這形容詞曾被當做名詞來用,例如「a bygone」(過去的事)。雖然這個字的意義原本純為中性的,但後來在指過去的事或情況時,多少暗示了這些過去的事是負面的,例如「let bygones be bygones」這個片語:讓我們之間的不愉快成為過去吧。「bygone」一字作名詞用可追溯至一五六○年代。

孔子(西元前五五一~四七九年)肯定沒有迴避過去,或暗示要忽略過去。實際上,他大部分的思想都是基於對回歸西周早期黃金時代的想望──這是周文王、武王、周公等聖賢治理下的時代。然而,孔子也勸誡人們,不要對未知或過去不可考的事物加以詮釋。

《論語》的〈八佾〉篇說到,魯哀公向孔子的學生宰我詢問,供奉土地神的神龕應該要用什麼木材來做比較好。宰我回答說,在夏朝是用松木,商朝用柏木,而周朝則用栗木。當時,栗樹「栗」字也用在「戰栗」一詞,意為「顫抖」。宰我補充說,「曰使民戰栗」(據說這是要使人民害怕顫抖)。孔子聽聞此事,便說:「成事不說,遂事不諫,既往不咎」(過去已做的事不該再試圖解釋,已經做了的事不必再挽救,已經過去的事也不該再強加詮釋)。成語「既往不咎」即源於此,意為過去的事被原諒、免去其罪。換句話說,如同上述英文片語「let bygones be bygones」,「既往不咎」所指的過去的事,亦含有某種不幸的事件、不愉快或犯罪之意。

後世文學中使用這成語的例子,可見於明清時期編纂的小說《東周列國志》──在第三十五章中,晉懷公向跟隨他伯父重耳公子流亡國外的前臣發出最後通牒,說若他們在三個月內回國,則「仍復舊職,既往不咎」(仍舊恢復他們以前的職位,過去的事就會算了,不再追究)。

(台北時報林俐凱譯)

這法規在詮釋上有很多問題,主管機關應修法,將規定釐清,讓人有所依循,並對過去的違法情事既往不咎。

(There are problems with the interpretation of this law. The competent authorities should amend it, to clarify it and make it easier to comply with, and past violations should be considered null and void.)

你們既然決定要結婚,過去的事就該既往不咎,別再舊事重提、傷害彼此感情。

(Since the two of you are to be married, you must let bygones be bygones. Do not rake through the past, it will harm your relationship.)

英文練習

let bygones be bygones

The word “bygone” is an adjective formed of a past participle and preposition, in the same way the word “aforesaid” is. Where “aforesaid” means “that which was said before,” “bygone” means “that which has gone by.” Although the word has mostly fallen into disuse, it still appears in phrases such as “bygone days” or “a bygone era.”

The adjective was once also used in noun form, as “a bygone.” While this was originally purely neutral, it was later to suggest the past events or situation to which it was referring were somehow negative. It is in this sense that it is used in the phrase “let bygones be bygones”: Let the unpleasantness between us be something of the past. The noun dates from the 1560s.

The ancient Chinese philosopher Confucius (551-479BC) certainly did not eschew the past, or even suggest that we disregard it. In fact, much of his philosophy was based upon his aspiration for a return to a golden age of governance by the sagely rulers — King Wen, King Wu and the Duke of Zhou — that governed during the very early years of the Zhou Dynasty. He did, however, counsel against assuming interpretations of things which were unknowable or lost in the midst of time.

The ba yi chapter of the Analects relates the story of how Duke Ai of the State of Lu asked one of Confucius’ students, Zai Wo, about the materials used for the construction of the altars of the spirits of the land. Zai Wo replied that in the Xia Dynasty they used pine; in the Shang the cypress; and in the Zhou the wood of the chestnut tree. At the time, the Chinese character for the chestnut tree, 栗 li, was also used in the word 戰栗 zhan li, meaning “to tremble.” Zao Wo then added 曰使民戰栗: “It is said this was done to inspire awe in the people.” On hearing this, Confucius said 成事不說,遂事不諫,既往不咎 (one should not attempt to interpret that which has passed, nor seek remedies for that which is done, nor should one try to read into what is now past). From this, we get the idiom 既往不咎, meaning to forgive and not bear recriminations. In other words, as in the aforesaid English phrase, the implication is that the bygone matter is some form of unfortunate event, unpleasantness or offence.

An example of how the idiom was used in later literature can be found in the novel Chronicles of the Eastern Zhou Kingdoms, compiled in the Ming and Qing dynasties. In Chapter 35, Duke Huai, the ruler of the state of Jin, issued an ultimatum to former Jin officials who had followed his uncle, Prince Chong E, into exile. The ruler assured them that if they returned within three months, 仍復舊職,既往不咎 (they could resume their former positions, and he would let bygones be bygones).

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

Can’t you two just put your differences aside and let bygones be bygones?

(你們兩個難道不能拋開歧見、既往不咎嗎?)

In the end, they decided to let bygones be bygones and shook hands.

(最後,他們決定既往不咎,握手言和。)

In an effort to fight phone scams, British mobile phone company O2 has introduced Daisy, an AI designed to engage phone con artists in time-wasting conversations. Daisy is portrayed as a kindly British granny, exploiting scammers’ tendency to target the elderly. Her voice, based on a real grandmother’s for authenticity, adds to her credibility in the role. “O2” has distributed several dedicated phone numbers online to direct scammers to Daisy instead of actual customers. When Daisy receives a call, she translates the scammers’ spoken words into text and then responds to them accordingly through a text-to-speech system. Remarkably, Daisy

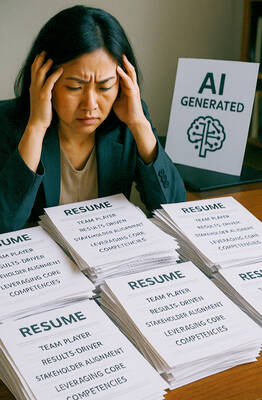

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Emma had reviewed 41 resumes that morning. While the ATS screened out 288 unqualified, she screened for AI slop. She could spot it a mile away. She muttered AI buzzwords like curses under her breath. “Team player.” “Results-driven.” “Stakeholder alignment.” “Leveraging core competencies.” Each resume reeked of AI modeling: a cemetery of cliches, tombstones of personality. AI wasn’t just changing hiring. It was draining the humanity from it. Then she found it: a plain PDF cover letter. No template. No design flourishes. The first line read: “I once tried to automate my

Every May 1, Hawaii comes alive with Lei Day, a festival celebrating the rich culture and spirit of the islands. Initiated in 1927 by the poet Don Blanding, Lei Day began as a tribute to the Hawaiian custom of making and wearing leis. The idea was quickly adopted and officially recognized as a holiday in 1929, and leis have since become a symbol of local pride and cultural preservation. In Hawaiian culture, leis are more than decorative garlands made from flowers, shells or feathers. For Hawaiians, giving a lei is as natural as saying “aloha.” It shows love and

1. 他走出門,左右看一下,就過了馬路。 ˇ He walked outside, looked left and right, and crossed the road. χ He walked outside and looked left and right, crossed the road. 註︰並列連接詞 and 在這句中連接三個述語。一般的結構是 x, y, and z。x and y and z 是加強語氣的結構,x and y, z 則不可以。 2. 他們知道自己的弱點以及如何趕上其他競爭者。 ˇ They saw where their weak points lay and how they could catch up with the other competitors. χ They saw where their weak points lay and how to catch up with the other competitors. 註:and 一般連接同等成分,結構相等的單詞、片語或子句。誤句中 and 的前面是子句,後面是不定詞片語,不能用 and 連接,必須把不定詞片語改為子句,and 前後的結構才相等。 3. 她坐上計程車,直接到機場。 ˇ She took a cab, which took her straight to the airport. ˇ She took a cab and it took her straight