Chinese practice

甘拜下風

(gan1 bai4 xia4 feng1)

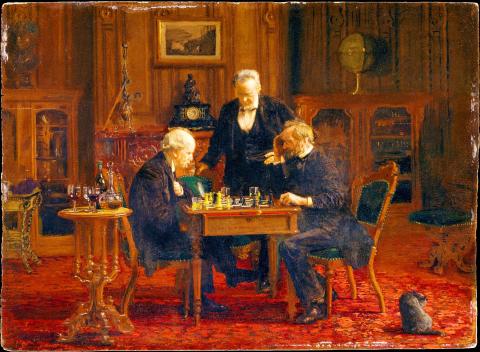

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

to willingly acknowledge others’ superiority

若我們說某人「佔上風」,表示這個人在競爭中居於優勢,獲勝的機會大,若是「居下風」,則是居於劣勢,很有可能會落敗。「上風」的原意為,風吹過來時,站在風頭;因此居於「下風」,就是在風尾了。

成語「甘拜下風」,字面意義為「心甘願情願居於風尾的位置」,語出《左傳.僖公十五年》:晉國發生饑荒,秦國將糧食輸往晉國紓困,後來,秦國也發生了饑荒,但晉國卻忘恩負義,拒絕援救秦國。秦穆公大怒,便派兵攻打晉國,俘虜了晉惠公。晉國的大臣們拔了營,披頭散髮地跟在後面如喪家之犬,秦穆公見他們如此狼狽憂傷,便說,你們晉國人都知道,你們幾年前死去的太子託夢說,以後要讓秦國來祭祀他,我現在只不過是實現了上天的旨意而已,一點都不過份。

晉國的大臣一聽,便向秦穆公叩頭說:「君履后土而戴皇天,皇天后土實聞君之言,群臣敢在下風」(大王您腳踩著后土,頭頂著皇天,皇天后土都聽到了您的話,我們在下邊聽候您的吩咐)。

另外,《莊子.在宥》也提到,黃帝去見廣成子,「順下風膝行而進」(沿下風處跪著前進)。由此可見,「下風」很早就有自承卑微而順服的意思,後來演變成「甘拜下風」這個成語。

在英文中,「throwing in the towel 」一語則表示勉強承認失敗。

早在十八世紀,海綿就是拳擊比賽場的必備用品,在比賽回合之間用來幫拳擊手擦臉。如果一個拳擊手眼看要輸了比賽,他的教練或隊友就會把一塊海綿扔進場中,表示承認己方失敗,以免選手繼續挨打、受傷過重。

一八六○年版的《Slang Dictionary》(俚語詞典)中,收錄了片語「to throw up the sponge」(把海綿丟上來),意指在拳擊賽中屈服、承認失敗。

後來,毛巾取代了海綿,變成「to throw in the towel」(把毛巾丟進來)。隨著時間的推移,這個片語的用法不僅限於拳擊場,在其他情況中也用來比喻放棄的意思。現今無論是在體育競賽、棋賽、對付難纏任性的小孩,或是其他競逐中,若要認輸,我們可以說「throw in the towel」。

「Throw in the towel」與中文成語「甘拜下風」的意思仍有一些差距:「甘拜下風」是指認輸的人自承不如對方,而心甘情願認輸;然而,「throw in the towel」只是在當下承認自己輸了,對方贏了或許只是僥倖,但明天又是新的一天,可以再一決勝負。

(台北時報林俐凱譯)

這個新創公司上週發表了新款手機,它的螢幕色彩,就連電子一哥也甘拜下風。

(This new start-up last week announced a new phone, and even the industry leader would have to concede the screen colors were better than theirs.)

你們的球隊無論在球員素質或是戰術上,都令人難以超越,我們甘拜下風。

(Your team was quite formidable, both in the quality of your players and your tactics. You were definitely the better team.)

英文練習

to throw in the towel

If we say a given person is 佔上風 (literally, occupying an upwind position), we mean that person has the advantage in a contest, and will probably win. Conversely, if we say they 居下風 (literally, occupy the ground downwind), we mean they are at a disadvantage, and are likely to lose. The original meaning of 上風 suggests standing with the wind at your back; 下風 implies that you are laboring against it.

The Chinese idiom 甘拜下風 literally means that you are willing to bow down, from a position downwind. It derives from the 15th Year of Duke Xi chapter of the ancient Chinese classic zuo zhuan (Commentary of Zuo) , which relates the following story: There was a famine in the state of Jin, and the state of Qin sent food. Later, Qin itself was hit with a famine, but Jin, forgetting the charity Qin had shown, refused to help. Duke Mu of Qin was enraged, and sent an army to attack Jin, taking Duke Hui of Jin captive. Senior Jin officials, returning as captives with the army to Qin, cut a sorry figure, looking shaken and disheveled. When Duke Mu saw how pitiful they looked, he said, “People of Jin, as you know, your own prince, years since dead, had a dream in which he saw that you would be giving tribute to Qin. Here I am simply realizing Heaven’s will, and nothing more.”

When the Jin officials heard this, they kneeled and pressed their foreheads to the ground, and said, “君履后土而戴皇天,皇天后土實聞君之言,群臣敢在下風” (my lord, you stand with your feet on the Earth below, while your head reaches Heaven above: Your words are heard through Heaven and Earth, and we stand laboring against the wind, awaiting your command).

In addition, the zai you (Letting Be, and Exercising Forbearance) chapter of the ancient Taoist classic Zhuangzi talks of how when Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor, went to see the sage Guang Chengzi, he 順下風膝行而進 (crawled on his knees, against the wind). From this we can see that, even from very early times, 下風 denoted subjugating yourself, and assuming a very lowly position. From this we get the idiom 甘拜下風.

In English, the phrase “throwing in the towel” is used to express conceding defeat.

As early as the 18th century sponges were used as ringside accessories during boxing matches to clean the fighters’ faces between rounds. When it became obvious that a fighter was going to lose the match, and to prevent him from being unnecessarily hurt any further than he already was, his coach, or another member of his team, would throw a sponge into the ring, to indicate that they conceded defeat.

In the 1860 edition of the Slang Dictionary, there is an entry for the phrase “to throw up the sponge,” meaning to submit, to concede defeat, in a boxing match.

Later on, towels replaced the sponge, and “to throw in the towel” came to be used instead. Over time, this would be extended beyond the boxing match, and used metaphorically for giving up in other contexts, too. Nowadays, we say “throw in the towel” when we mean we give up, be it in sports contests, board games, dealing with impossibly unruly children, or any other situation.

There is a difference in the meaning of the Chinese and the English idioms here, however. With 甘拜下風, the person conceding defeat is acknowledging they are not as good as their opponent, and are quite willing to admit this. With throwing in the towel, the concession is limited to the present occasion only. Tomorrow is another day.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

I’m exhausted, I’m out of ideas and nothing seems to work. I’m ready to throw in the towel.

(我累壞了,我已經絞盡腦汁,可是都看不出成效。我準備要放棄了。)

You can’t throw in the towel now, not after you have come so far. Take a few days off, come back refreshed and reconsider.

(你現在不可以放棄,你都已經做到這個地步了。你休息個幾天吧,轉換一下心情,等回來以後再重新考慮。)

A: Apart from the Taipei Music Center’s exhibit and concert, US pop rock band OneRepublic and rapper Doja Cat are touring Kaohsiung this weekend. B: OneRepublic is so popular that after tonight’s show at the K-Arena, they are set to return to Taiwan again in March next year. A: And Doja will also perform at the same venue on Sunday, right? B: Yup. Her collab with Blackpink’s Lisa and singer Raye for the song “Born Again” has been a huge worldwide success. A: Doja even made it on Time magazine’s “100 Most Influential People” list in 2023. She’s so cool. A: 本週末除了北流的特展和演唱會外,美國男團共和世代和饒舌歌手蜜桃貓朵佳也將來台開唱。 B: 共和世代因太受歡迎,繼今晚高雄巨蛋的演唱會後,預計明年3月即將再度來台巡演唷。 A: 朵佳本週日將在同場地開唱,對不對?

A: What show are you watching online? B: I’m watching “Fly Me to the Moon & Back” – an exhibition launched by the Taipei Music Center (TMC) to commemorate the late singer Tom Chang. A: Known for his sky-high notes, Chang is praised as one of the best singers in the 1990s. His death at the age of 31 was a major loss indeed. B: And I’m so glad that we went to the TMC’s 90s-themed concert last Friday. I finally saw the iconic “Godmother of Rock” WaWa perform live. A: This year-end show also featured singers Princess Ai, Bii, Wayne Huang, PoLin and

Just like fingerprints, your breathing patterns may serve as a definitive identifier. In a recent study, scientists have demonstrated an astonishing 96.8% accuracy in identifying individuals based on their respiratory patterns. This revelation could open up new possibilities in biometrics and personalized health monitoring. The notion of using individual breathing patterns as a distinct biological signature has long been a topic of discussion within the respiratory science community, yet a practical method for measurement remained elusive. This changed with the invention of a tiny, wearable device capable of extended recording. Researchers deployed a lightweight tube designed to fit inside

In most cities, food waste is often regarded as one of the most troublesome types of waste: it has a high moisture content, spoils easily and produces strong odors. If not handled properly, it can cause serious sanitation and environmental problems. From the perspective of the circular economy, however, food waste is not “useless leftovers,” but rather an organic resource that has yet to be effectively utilized. The core principle of the circular economy is to break away from the linear model of “production–consumption–disposal,” allowing resources to circulate repeatedly within a system and extending their useful life. Food waste occupies a