In the previous Bilingual Arts we introduced a piece of calligraphy to explore the interrelation of subject matter and the visual form of the characters within the calligraphic medium. Chinese characters and the brush form the core of the East Asian culture. The brush is not only an instrument for writing and expressing ideas: it is also an implement used for painting.

The Chinese literati would speak of how painting and poetry resonated with each other, one evoking the other, and of the relationship between poetry, painting and calligraphy. The artist’s approach was informed by the concept that poetry and painting have a shared origin, a theory originating from the essay “On the use of the brush by Gu, Lu, Zhang and Wu” in Famous paintings through History by the Tang writer Zhang Yanyuan (815-875 AD). The concept of yongbi — the use of the brush — is first seen in the Record of the Classification of Old Painters (completed approx. 532-552 AD) by Xie He (dates unknown) of the Southern Qi dynasty, who wrote of the “six principles of Chinese painting,” which are interpreted as resonance (qiyun shengdong); outlining compositional elements with the brush (gufa yongbi); accurate depiction of form (yingwu xiangxing); fidelity of form and color (suilei fucai); composition (jingying weizhi); and transmission through copying (chuanyi moxie). Zhang’s concept of the shared origin of painting and calligraphy laid the theoretical foundations for the calligraphic use of the brush to be applied to painting.

Calligraphy is more than a linear representation: through variations in the amount of ink on the brush the calligrapher creates the impression of spatial depth on the two-dimensional surface of the paper or silk.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

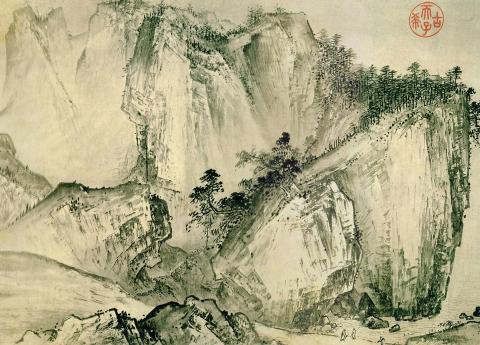

The Chinese character cun originally meant the tiny lines or cracks that appeared in the skin of the face dried out by long exposure to cold winds. The cunfa — texture stoke — technique is used in landscape painting to represent trees and rocks.

During a painting, cun entailed dipping the brush in ink and water and then wiping it on a separate piece of paper to absorb some of the liquid. The artist would then draw the semi-dry brush, perpendicularly or obliquely, across the textured surface of the paper or silk. This would naturally create a dry brush effect, leaving textured traces of ink reminiscent of axe cuts.

The precipice shown in this central section of Pure and Remote View of Streams and Mountains by the Song Dynasty painter Xia Gui (active approx. 1200~1230 AD) is painted using the fupicun — axe-cut texture stroke — technique to create a layering effect and to differentiate rocks, while also giving them the impression of substance and weight. The artist would draw in the outlines of the precipice with a brush liberally loaded with ink, using it to differentiate the different layers of rock, and then paint on the finer lines on the rock surface using a lighter tone of ink and employing the zhongfeng — perpendicular to the paper, using the the brush along its central axis — method. Finally, he would have etched on the surface texture of the rock, with protrusions and crevasses, in the axe-cut texture stroke using the cunfa technique.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

This cunfa technique lies somewhere between rendering lines and textures: if using the zhongfeng method, one can depict lines; if using the cefeng (oblique attack) method, one can give the impression of a surface texture.

(Translated by Paul Cooper)

上回雙語藝術單元我們簡介了一件書法作品,說明在書法這媒介中,詩文內容以及文字視覺形象的並陳。漢字與毛筆,構成了東亞漢字文化圈的核心。而毛筆不僅用來書寫、表意,更是繪畫的工具。

不僅是文人標榜的詩中有畫、畫中有詩,或詩書畫合一,在創作實踐上,更有「詩畫同源」說——此為唐代張彥遠(西元八一五~八七五年)在其《歷代名畫記》中的〈論顧陸張吳用筆〉所提出。「用筆」一詞,最早見於南齊謝赫(其生平不詳)《古畫品錄》(成書年代約為西元五三二~五五二年)的繪畫「六法」:氣韻生動、骨法用筆、應物象形、隨類賦彩、經營位置、傳移模寫。

張彥遠的「書畫同源」論奠定了以書法「用筆」入畫的理論基礎,也開展了未來以「筆法」作為中國繪畫創作基本教義之一。

書法不僅是線性的,利用墨汁之濃淡乾溼變化,便可在紙或絹上堆疊出立體感。皴法即為山水畫中用以描繪樹石紋理的技法。皴(音村)的原意為人在寒冬經冷風長久吹襲,臉上皮膚缺少油脂保護,受凍所形成的細小粗糙之裂紋。

皴在繪畫造形上,是筆蘸墨與水,以另一張紙捻吸使筆半乾,然後以中鋒或側鋒擦過紙絹面,因紙絹面本身即有紋理高低,受墨不平均,因而形成類似皴破之裂紋肌理。

南宋夏圭(約活躍於一二○○~一二三○年)的《溪山清遠》中段的巨崖,即用斧劈皴呈現不同量塊的風貌與萬鈞的厚實感。先以較濃之墨勾勒出巨巖不同塊面之輪廓,並區別出石塊前後之位置,再以淡墨中鋒勾勒石上絡脈,然後以乾筆皴擦出狀如斧劈陰陽凹凸的石面紋路。

皴之表現,可介於線與面之間,如以中鋒皴擦,則類似線;如以側鋒為之,則成小的面。

(台北時報林俐凱)

In an effort to fight phone scams, British mobile phone company O2 has introduced Daisy, an AI designed to engage phone con artists in time-wasting conversations. Daisy is portrayed as a kindly British granny, exploiting scammers’ tendency to target the elderly. Her voice, based on a real grandmother’s for authenticity, adds to her credibility in the role. “O2” has distributed several dedicated phone numbers online to direct scammers to Daisy instead of actual customers. When Daisy receives a call, she translates the scammers’ spoken words into text and then responds to them accordingly through a text-to-speech system. Remarkably, Daisy

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 Emma had reviewed 41 resumes that morning. While the ATS screened out 288 unqualified, she screened for AI slop. She could spot it a mile away. She muttered AI buzzwords like curses under her breath. “Team player.” “Results-driven.” “Stakeholder alignment.” “Leveraging core competencies.” Each resume reeked of AI modeling: a cemetery of cliches, tombstones of personality. AI wasn’t just changing hiring. It was draining the humanity from it. Then she found it: a plain PDF cover letter. No template. No design flourishes. The first line read: “I once tried to automate my

Every May 1, Hawaii comes alive with Lei Day, a festival celebrating the rich culture and spirit of the islands. Initiated in 1927 by the poet Don Blanding, Lei Day began as a tribute to the Hawaiian custom of making and wearing leis. The idea was quickly adopted and officially recognized as a holiday in 1929, and leis have since become a symbol of local pride and cultural preservation. In Hawaiian culture, leis are more than decorative garlands made from flowers, shells or feathers. For Hawaiians, giving a lei is as natural as saying “aloha.” It shows love and

1. 他走出門,左右看一下,就過了馬路。 ˇ He walked outside, looked left and right, and crossed the road. χ He walked outside and looked left and right, crossed the road. 註︰並列連接詞 and 在這句中連接三個述語。一般的結構是 x, y, and z。x and y and z 是加強語氣的結構,x and y, z 則不可以。 2. 他們知道自己的弱點以及如何趕上其他競爭者。 ˇ They saw where their weak points lay and how they could catch up with the other competitors. χ They saw where their weak points lay and how to catch up with the other competitors. 註:and 一般連接同等成分,結構相等的單詞、片語或子句。誤句中 and 的前面是子句,後面是不定詞片語,不能用 and 連接,必須把不定詞片語改為子句,and 前後的結構才相等。 3. 她坐上計程車,直接到機場。 ˇ She took a cab, which took her straight to the airport. ˇ She took a cab and it took her straight