Chinese Practice

逝者如斯夫,不舍晝夜

All that passes is like a river,

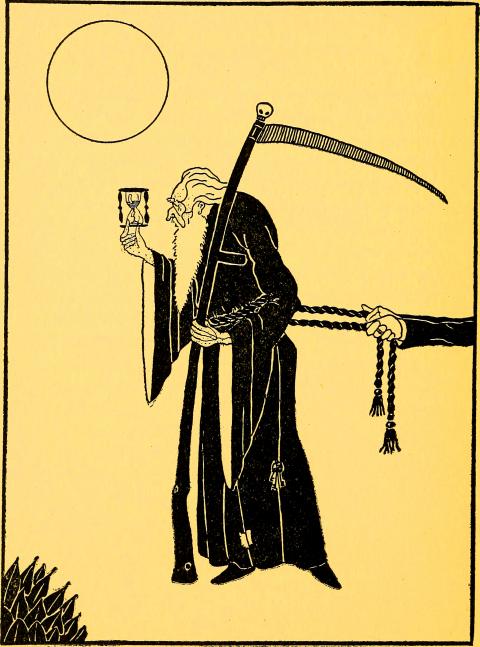

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

照片:維基共享資源

flowing continuously

(shi4 zhe3 ru2 si1 fu2 bu4 she3 zhou4 ye4)

《論語》〈子罕〉篇有一句寫道:「子在川上曰:逝者如斯夫!不舍晝夜。」意思是說,孔子站在河邊嘆道:「那些流逝的就像這河水,是日日夜夜不斷地在流逝。」後世對這比喻或有不同的詮釋,但「逝者如斯夫,不舍晝夜」這句話現用來指光陰的流逝,以及時間的寶貴。

英文有句類似的說法,也將流水比喻作時間:「time and tide wait for no man」(時間與潮汐是不等人的),意思是說,我們該把握機會,因它可能稍縱即逝。而這句話的演變有些曲折。

此句一般認為出自英國文豪喬叟(西元一三四三~一四○○年)所著,於一三六八年出版的《學者的故事》其中一句:「For thogh we slepe, or wake, or rome, or ryde, Ay fleeth the tyme; it nyl no man abyde 」(因即便我們無論是睡或醒,或漫步,或騎馬,時間永遠在消逝;時間不等任何人)。

但是喬叟所寫下的只有「時間」,他並沒有提到「潮汐」。

紀錄中最早使用「time and tide」(時間與潮汐)的是一二二五年——也就是年代較喬叟早一百多年的聖馬荷的著作中。聖馬荷的生平似乎鮮為人知,他寫道:「你出生的潮汐與時間應受祝福。」此句雖非描述時間之流逝,但其中tide(潮汐)一字便是時間的同義詞。

現今英語中的「tide」一字指海面升降、一天兩次漲退的潮水。但在聖馬荷的年代,「tide」是由古英語字「tid」演變而來,其意為「時間中的一點或一段時間、到期日、時期或季節」。這個字在十四世紀中才有現今的「潮汐」的意義。因此聖荷馬原文中的「time」及「tide」兩個字的意義相同。

因此,後來「time and tide」這說法便結合了喬叟原句的含意,而成了現今的「Time and tide wait for no man」這句話。

(台北時報編譯林俐凱譯)

逝者如斯夫,不舍晝夜。我們該把握時間,趁早努力,以免老大徒傷悲。

(Time and tide wait for no man. We should seize opportunities as they arise, lest we regret lost opportunities in our dotage.)

英文練習

Time and tide wait for no man

In the Zi Han chapter of the Analects of Confucius, it says, 子在川上曰:逝者如斯夫!不舍晝夜. Translated, this means “Confucius, standing on the river bank, lamented: ’that which passes is like this river, flowing unceasingly, day and night’.” While different interpretations of this metaphor have been ventured throughout history, the phrase 逝者如斯夫,不舍晝夜 has come to refer to the passage of time, and of time as something to be valued.

The link between time and water appears in an English equivalent, “time and tide wait for no man,” meaning that one should make use of an opportunity, as you might not have the chance later. The evolution of the phrase, however, is a little complicated.

It is generally attributed to Geoffrey Chaucer (1343-1400) who, in the Prologue to the Clerk’s Tale (1368), wrote “For thogh we slepe, or wake, or rome, or ryde, Ay fleeth the tyme; it nyl no man abyde (For though we sleep or wake, or roam, or ride, time forever flees; it will tarry [wait] for no person.)

But Chaucer only uses the word “time”; he makes no mention of “tide.”

The earliest recorded usage of “time and tide” appears in the writings of a St. Marher — of whom little seems to be known — in 1225, over a century before. Translated into modern English, he wrote, “And the tide and the time that you were born shall be blessed.” Although St. Marher was not talking about the passage of time, he was using a phrase in which tide was equated with time.

The modern usage of “tide” refers to the alternate rising and falling of the surface of the ocean, usually twice a day. In St. Marher’s time, however, it meant “a point or portion of time, due time, period or season,” deriving from the Old English word “tid.” The modern meaning was given to the word in the mid-14th century. Time and tide, in the phrase, are essentially one and the same thing.

This combination was subsequently combined with Chaucer’s allusion to form the modern version of the phrase.

(Paul Cooper, Taipei Times)

You’d better start preparing for the new job. You know what they say about time and tide...

(你最好為新工作及早做好準備。你知道時間是不等人的。)

The content recommendation algorithm that powers the online short video platform TikTok has once again come under the spotlight after the app’s Chinese owner ByteDance signed binding agreements to form a joint venture that will hand control of operations of TikTok’s US app to American and global investors, including cloud computing company Oracle. Here is what we know so far about its fate, following the establishment of the joint venture. IS BYTEDANCE CEDING CONTROL? While the creation of this new entity marks a big step toward avoiding a US ban, as well as easing trade and tech-related tensions between Washington and Beijing, there

A: Happy New Year! I can’t believe it’s 2026 already. Where did you count down? B: I went to pop singer A-mei’s Taitung concert yesterday for the New Year’s countdown. How about you? A: I went to rock band Mayday’s Taichung concert yesterday. Going to their New Year’s shows has become a holiday tradition for me. B: Don’t forget, we’re also going to Jolin Tsai’s show tonight. It’s her first perfomance at the Taipei Dome. A: Yeah, that’s right. It’s great to start the year with good friends and good music. A: 新年快樂!我真不敢相信都已經2026年了。你昨天去哪跨年啦? B: 我昨天去了流行天后張惠妹的台東演唱會,還和她一起跨年倒數。那你呢? A:

Prompted by military threats from Russia, Denmark has recently passed a new conscription law, officially including women in its military draft for the first time. From July 1, 2025, Danish women, upon turning 18, will be entered into the draft lottery. If selected, they are to serve in the military for 11 months, just as men do. Not only has this decision attracted international attention, but it has also sparked discussions on gender, equality and national defense. Although Denmark’s reform appears to promote gender equality, it primarily responds to regional instability and the need to strengthen national defense. With

A: Apart from Taiwan’s A-mei, Mayday and Jolin Tsai, there are many foreign singers coming to Taiwan early this year. B: The South Korean girl group Babymonster are playing two shows at Taipei Arena starting from tonight. Who else is coming to Taiwan? A: Other artists include Australian band Air Supply, K-pop superstar Rain, boy group Super Junior, TXT, US singers Giveon and Josh Groban, and Irish boy group Westlife. B: Air Supply was the first foreign band to come to Taiwan in 1983, and they’re probably the most frequently visiting group too. A: As the year is beginning