A disgruntled viewer is suing Japan’s national broadcaster for mental distress caused by an excessive use of words borrowed from English.

Hoji Takahashi, 71, is seeking 1.4 million yen (US$13,700) in damages from NHK.

“The basis of his concern is that Japan is being too Americanized,” his lawyer Mutsuo Miyata told the news agency AFP.

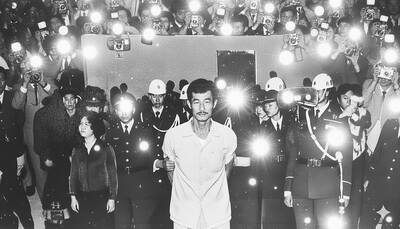

Photo: AFP

照片:法新社

English became more prevalent in Japan after World War II during the US-led occupation. This was followed by a growing interest in American pop culture.

The country’s modern vocabulary is littered with borrowed words, many of which are changed to fit the Japanese phonic structure.

Takahashi, who is a member of a campaign group supporting the Japanese language, highlighted words such as “toraburu” (trouble), “risuku” (risk) and “shisutemu” (system) in NHK’s news and entertainment programs.

He accused NHK of irresponsibility by refusing to use native Japanese equivalents.

(Liberty Times)

一位心有不滿的觀眾控告日本的國家電視台過度使用英語外來詞,令他精神飽受折磨。

現年七十一歲的高橋鵬二(譯音)尋求向NHK電視台索取一百四十萬日圓(一萬三千七百美元)損害賠償金。

他的代理律師宮田康弘(譯音)對法新社說:「他主要擔心日本過度美國化。」

二戰後,美國占領日本期間,英語在日本變得更普及。隨之而來的是日本民眾對美國流行文化日益高漲的興趣。

日本的現代詞彙中充斥著外來詞,其中大部分外語詞經過修改,以適應日語的語音結構。

高橋鵬二是支持日語活動團體的成員,特別指出NHK電視台的新聞節目和娛樂節目大量使用toraburu(trouble)、risuku(risk)和shisutemu(system)等外語單詞。

他指責NHK拒絕使用本土的日語同義語,很不負責任。

(自由時報/翻譯:陳成良)

When people talk about fast delivery or logistics, most assume these are modern inventions. However, the need to convey messages and ship goods efficiently existed in ancient China. As early as the Shang and Zhou dynasties, the governments implemented official systems to deliver orders and military information across long distances. Later, this system, known as yizhan, reached its peak during the Tang period and remained crucial to Chinese society for centuries. The main function of a yizhan was to deploy documents and personnel quickly across vast regions. Messengers would stop at these stations to change horses or rest. Sometimes,

Bilingual Story is a fictionalized account. 雙語故事部分內容純屬虛構。 “Sentence me to death! I beg you — I beg you!” He stood, thin from weeks in a cell, but steady. The courtroom was silent. Soldiers lined the walls. Reporters looked up, pens suspended above their notebooks. The judges shifted. Cameras clicked once, then stopped. Outside, the sun blazed over the barracks yard. Inside, it was winter. The words rebellion and death penalty hung in the air like a storm cloud about to break. But this moment had not begun here. It began three months earlier, on a warm December evening. The traffic circle

1. 我離開香港前會來看你。 ˇ I will come to see you before I leave Hong Kong. χ I will come to see you before I will leave Hong Kong. 註:表示未來的時間副詞從屬句通常用一般現在時態,但用 when 引導的名詞從屬句,如表示未來,則必須用將來時態,試觀察下列各句: I will have finished my work by the time he returns. As soon as he comes, we will start working. I don’t know when he will come; but when he does, I will speak to him. 2. 他打開門,拔腿就逃。 ˇ He opened the door and ran off. χ He opened the door and runs off. 註:在同一句中,兩個動詞表示的動作雖有先後,但都屬過去的範疇,動詞該用過去時態。 3. 他昨天告訴我他暑假期間要到泰國去。 ˇ Yesterday he told me that he was going to Thailand for the summer vacation. χ Yesterday he told me that

對話 Dialogue 清清:你知道嗎?今年臺北士林官邸的菊花展開始了。 Qīngqing: Nǐ zhīdào ma? Jīnnián Táiběi Shìlín Guāndǐ de júhuā zhǎn kāishǐ le. 華華:真的嗎?我想去看!要買門票嗎? Huáhua: Zhēnde ma? Wǒ xiǎng qù kàn! Yào mǎi ménpiào ma? 清清:不用,是免費的。 Qīngqing: Búyòng, shì miǎnfèi de. 華華:太好了!怎麼去比較方便? Huáhua: Tài hǎo le! Zěnme qù bǐjiào fāngbiàn? 清清:先坐捷運到士林站,再走十分鐘就到了。 Qīngqing: Xiān zuò jiéyùn dào Shìlín Zhàn, zài zǒu shífēnzhōng jiù dào le. 華華:也可以搭公車嗎? Huáhua: Yě kěyǐ dā gōngchē ma? 清清:可以,有很多公車到中山北路那邊,下車以後就離士林官邸不遠了。 Qīngqing: Kěyǐ, yǒu hěnduō gōngchē dào Zhōngshān Běilù nèibiān, xiàchē yǐhòu jiù lí Shìlín Guāndǐ bù yuǎn le. 華華:好,那週末就一起去吧! Huáhua: Hǎo, nà zhōumò jiù yìqǐ qù ba! 翻譯 Translation Qingqing: Do you know? This year’s Chrysanthemum Exhibition at Taipei’s Shilin Residence has begun. Huahua: Really? I want to go see it. Do we