It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.”

As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese, says that as early as the 1580s Spanish documents show that Spain thought of Taiwan as part of the Philippines and just as much a Spanish possession. In 1586 the governor of Manila and a council of 50 local notables sent a letter to the King of Spain advising that Formosa be occupied, Andrade notes.

SPANISH COLONIALISM

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Kua points to the 1596 letter of Luis Perez Damsmarinas, then interim governor of Spain’s territories in the Far East, to the King of Spain warning of the importance of Isla Hermosa and advising the King to send a military expedition. A year later, Hernando Rios Coronel, who had helped lead the ill-fated Spanish invasion of Cambodia in the late 1580s, similarly memorialized the King. He argued that Spain needed ports on both the Chinese coast and on “Isla-Hermosa,” specifically identifying Keelung as a good candidate for a defensible port, and warned that the Japanese could move before Spain.

According to Andrade, this perception of Japan was widespread among the Spanish in the Philippines in the 1590s, because missionaries had brought back word of secret Japanese plans to seize Taiwan.

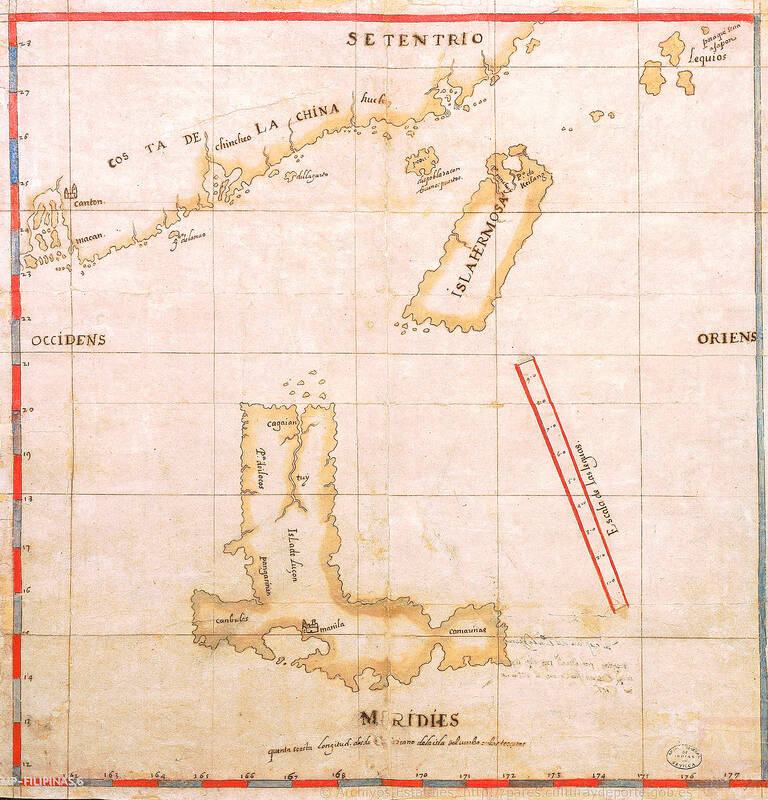

Today Coronel is largely remembered for drawing one of the first Spanish maps of Luzon, Taiwan and the Chinese coast, rendering Taiwan correctly as a single island (recall that until Taiwan’s rivers were dammed in modern times, they were wide and flat, making Taiwan appear to be 2-3 separate islands to early Western mariners).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Spanish fear of Japanese invasion was the natural outcome of Taiwan’s geography. Viewed from Manila, Taiwan with its Austronesian peoples is obviously related to the Philippines. Whereas, viewed from Tokyo, it appears to be an obvious southward extension of the Ryukyus, which was how modern Japanese strategists came to treat it.

Indeed, the Chinese themselves recognized the latter relation, confusingly naming Taiwan “Little Ryukyu” as opposed to Okinawa, which was “Big Ryukyu.” It was only after majority Han settlement that the “inevitable” relationship between China and Taiwan became a historical possibility. Without the Dutch, we would be talking about the Austronesian brotherhood of Taiwan and the Philippines. Indeed, when the Portuguese wrecked off Taiwan in 1582, their first recorded visit, they had with them a young man from Luzon who could communicate with the local Austronesians, according to a 17th-century account of the incident.

JAPANESE INTEREST

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Japanese interest in Taiwan was signaled in 1593 by a letter from Toyotomi Hideyoshi demanding submission and tribute. Of course, there was no centralized authority in Taiwan at the time. In 1609 Arima Harunobu, the Christian lord of Shimabara in Hizen province, sent an expedition to Taiwan but was driven off by the local Indigenous people. Another Japanese expedition in 1616 was scattered by a typhoon and ended up raiding the Chinese coast.

When the Dutch arrived in Tainan in 1624 they found Japanese and Chinese traders well established in the harbor there. In 1625 the Dutch cut off the Japanese from the silk trade. The loss of the Japanese trade inflicted a grievous budgetary blow on the Dutch colony, and the Dutch authorities considered abandoning it. The colonists on Formosa disagreed, arguing persuasively that the Spanish or the Portuguese would take over. Inevitably.

In 1635, one of the major events of Taiwan history took place, one that ended many might-have-beens: the Shogun cut Japan off from the outside world almost completely. Because this was a “non-” event, it is often overlooked, and yet it was formative.

Taiwan’s history would have been hugely different if the Dutch, Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, Koxinga) or the Manchus (Qing) had encountered a vigorous Japanese trading and state presence backed by an expansionist state policy. The People’s Republic of China’s “inevitable” annexation of Taiwan is historically plausible only because the Shogunate removed itself from the Taiwan chessboard.

SOVEREIGNTY ACHIEVED

As it was, during the period of Manchu control of western Taiwan, there were hundreds of shipwrecks of all nations, including ships from Ryukyu (Okinawa) and Japan. The 1874 invasion of southern Taiwan by Japan is often attributed to the 1871 Indigenous massacre of Okinawan sailors, an event known today as the Mudan Incident (牡丹社事件). In reality, decades of similar incidents may have helped drive the invasion, in addition to Japan’s desire to assert sovereignty over Okinawa, as Liu Shiuh-Feng (劉序楓), a historical specialist at Academia Sinica, has noted.

For example, in 1803 a ship from Hokkaido drifted into Kavalan, then just coming under Manchu administration. The local Indigenous people attacked the craft (robbery of wrecked ships and murder of seamen was common). The ship got away and wound up at the mouth of the Siuoguluan River (秀姑巒溪), where some Han merchants had established themselves. The crew of nine were taken off, but then subjected to forced labor. One by one they died, leaving only the captain.

In 1808 another Japanese ship appeared at the river mouth, and the stranded captain boarded it, heading for Fangliao. Eventually he made his way home and published an account of his adventures. He was not the only Japanese stranded for years among the Indigenous people.

Because Okinawa was controlled by Japan (it had been a vassal of Satsuma since 1609) but contested by the Manchus, the experiences of its stranded sailors became a political issue. The Japanese insisted that their Ryukyuan subjects be repatriated to Japan by the Manchus before being sent on to Okinawa, but the Manchus treated them as vassals and sent them directly to Okinawa if they went on Manchu vessels. Imagine what these policies would have looked like if Taiwan had been contested between the two imperial states and Okinawa had been a sideshow.

As history teaches, in the latter half of the 19th century, Japan developed a vigorous commercial policy that flooded northern Taiwan with Japanese products. Within a few decades of re-opening, it annexed Taiwan, making good on the letter of 1593. Imperialism delayed is not, it turns out, imperialism denied. Inevitable? Sure feels like it. Probably more so than Chinese annexation, which after centuries of contact, still remains only a possibility.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of

The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder — or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” — who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives. She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative. My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she