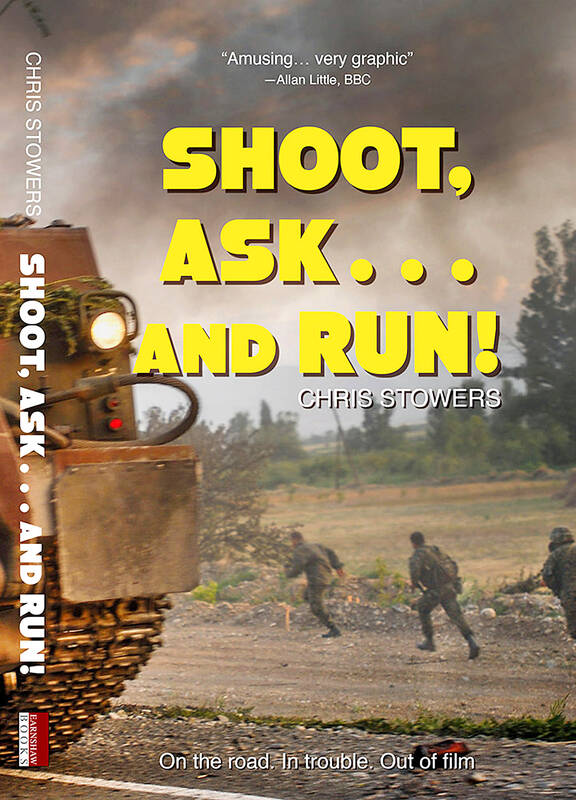

As much as I like using the phrase “The past is a foreign country,” it’s surprising to see it so aptly describe a period as recent as the early 1990s, the time setting of Shoot, Ask… and Run, a travelogue memoir by photojournalist Chris Stowers.

How different things were back then. The author’s first visit to Taiwan in 1991 is a good example. He sailed to Kaohsiung from Macau, then a Portuguese colony, on the MV Macmosa. The young Englishman, a fledgling freelancer, was here for the Double Ten Day parade, with unrest expected from student protesters, part of the pro-democracy Wild Lily Movement, which had made waves the previous year.

China’s Tiananmen crackdown was still a fresh memory and international media were in Taipei just in case sparks flew. Thankfully, however, there wasn’t much to report on. Typical of the non-escalation was a scene Stowers witnessed: two protesters hung a Republic of China (ROC) flag upside-down — an arrestable offense — then sprinted away, while police officers watched on. Would the police chase them or not?

“They chose the latter option, it being too hot to go running around being booed and jeered at.”

The title of the book comes from some advice, “shoot first, then ask ... and (when that fails) run!” given to him by two Australian photographers he met in Pakistan. That was Stowers’ first overseas adventure back in 1987, when the Mujahedeen were battling the Soviets. The Pakistan-Afghanistan borderlands “was a hell of a place to arrive fresh out of high school, innocent in the ways of the world.”

Before setting off from England, Stowers had also received some other wisdom.

‘FRENCH LETTERS’

“My dad’s parting advice was something garbled about ‘French letters’— the euphemism favored by his generation for condoms.”

The author adds that apocalyptic AIDS education at high school had left him terrified, thinking: “if I have sex, I’m going to die, horribly.”

And while living in Jakarta, this would come close to happening; an ill-fated romance with a local woman ended with her “enraged gangster-ex” attacking him with a machete.

Stowers fled to Borneo, where he spent a couple of months and made a long trek with Dayak guides through the rainforest. He beautifully captures the claustrophobic nature of travel in tropical forests, of seeing “nothing but trees all the way,” the thick humid air, the dark forest floor, and the noise.

“Cicadas, monkeys and birds combined to produce a deafening, multi-layered forest symphony that sounded for all the world like farmyard animals, chainsaws, ringing telephones and the squealing brakes of a slowing train.”

Much of Shoot, Ask… and Run centers around Hong Kong, Stowers’ base in the early 1990s. At that time, Hong Kong had a thriving magazine scene — the much-missed likes of Asiaweek and the Far Eastern Economic Review. The city is described with fondness. Returning to it after a nightmarish trip to China, Stowers expresses his delight at crossing the border.

“I allowed myself to be swamped by Hong Kong’s benevolent civic efficiency, like a trauma victim welcoming a huge shot of morphine.”

The third act of the book “The Long Way Home” takes us overland in 1992 from Hong Kong to Beijing and through a disintegrating Soviet Union and a Yugoslavia in flames. A near-fatal encounter with Serbian militia is a dramatic highlight, but most memorable for me was a warm encounter on the Trans-Siberian railway. Riding the rails from Ulan Bator to Moscow, Stowers shares the carriage with two Russian boys, 10 and 11, and their father, a foreman of a failed car factory in Mongolia, “part of an exodus of skilled workers flooding back to Mother Russia.”

But in the chaos of the time, the trio were traveling back under their own steam, their life’s belongings with them, which consisted mostly of books, “hundreds of volumes that strained the straps of their suitcases.”

Stowers befriends this bookish, chess-playing family, and berates himself for having harbored “a thick veneer of prejudice” acquired from his Afghan war experiences against the entire nationality.

Stowers’ book ends with his return home in 1992 after years away. He would soon be back in Hong Kong, from where he covered the region, including the story of Taiwan’s democratic progress. At the tail-end of 1995, he moved to Taiwan from his Hong Kong base, principally to cover the first presidential elections, and with Hong Kong’s 1997 return to China looming — he basically just stayed on, and has been here ever since.

Shoot, Ask… and Run draws on the author’s diaries which he meticulously kept, helping to give the writing rich sensory detail, an authenticity and immediacy. Diary entries, however, are often filled with the worries of the day — transport connections and dwindling finances — and perhaps a few too many of these did bleed into the book.

LOST WORLD

Stowers writes in delightful old-fashioned yet casual prose, which is a good match for the nostalgic feel of the memoir. In some ways, the early 1990s seem like a distant world, not just a different decade. These were the last days of British rule in Hong Kong, the final years of film cameras and a time when people read magazines.

Above all, it was the twilight of a golden age of travel — pre-Internet days and well before the blessings and curse of the smartphone — when there was a greater sense of mystery and discovery. Yes, things were harder — paper maps and hand-drawn directions, visits to post offices for a rare long-distance call and to collect poste restante mail, and so on — but the world was bigger and colored in Kodachrome.

The superb book, which includes some photographs, is the second in a series. The first, Bugis Nights, (reviewed by David Frazier in the June 15, 2023 edition of the Taipei Times) describes an epic 1988 voyage in a traditional Indonesia sailing ship.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has