With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation.

Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead.

Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century.

Photo: Bonnie White

Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty.

“People are influenced by fantasies, but [Bourgeois’] work is raw,” says co-curator Reiko Tsubaki.

Raised in her family’s tapestry restoration workshop, Bourgeois developed early craftsmanship. From marble to wood, steel to gouache, her skills became her language.

Photo: Bonnie White

The show unfolds in three main sections — motherhood, emotional struggle and reconciliation, reflecting Bourgeois’ lifelong engagement with family trauma, plus two columns showcasing some of her early works.

Adding a local touch, famous Taiwanese pop singer Stella Chang (張清芳) narrates the Chinese version of the audio guide.

MOTHER

Photo: Bonnie White

The opening chapter, “Do Not Abandon Me,” unravels Bourgeois’ relationship with motherhood.

The centrepiece Breast and the Blade (1991) captivates. From one angle, tender breasts cast in bronze are exposed; from another, a blade sticks out, guarding the socle.

In the corner, Nature Study (1984), a pink headless dog with six breasts, stands watch. The grotesque and maternal figure evokes unease and guardianship.

To Bourgeois, motherhood was both a burden and a source of creation. Her sculptures express the female body as a site of contradiction: nurturing yet wounded, exposed yet defiant.

The spider, a recurring motif in her work, is another metaphor: the fierce protector mending broken webs.

“My best friend was my mother, and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat and as useful as an araignee,” Bourgeois said in a 1995 interview.

FATHER

In the second chapter of the exhibition, “I’ve been to hell and back,” the exhibition turns inwards.

The space shrinks in the dim-lit room, echoing the claustrophobia of memory and rage.

Cages and erotic images overwhelm the viewer. The room exudes psychic pain and fractured bodies.

While her mother suffered from chronic illness, young Bourgeois endured her father’s decade-long affair with their house governess. This painful memory became a driving force in her art, allowing her to externalize her anger and unresolved grief.

“Making art became an outlet for Bourgeois to deal with pain,” co-curator Manabu Yahagi says.

The Destruction of the Father (1974) bathed in red light is embedded into the wall like a wound. Inside, gnawed flesh forms on a dinner table, luring visitors into Bourgeois’ childhood revenge fantasy of devouring her father.

RECONCIALIATION

Moving across to the last chapter, “Repairs in the Sky,” the mood shifts. Bourgeois’ fabric works from the restorative phase of her practice decorate the walls.

These pieces, made from salvaged household fabrics and objects once belonging to family members, embody her desire to physically mend the past.

Towering 15 feet, Spider (1997), from Bourgeois’ “Cell” series, anchors the room. The monumental bronze legs encase a cell adorned with tapestry scraps, symbolizing both maternal protection and the entrapment of memory.

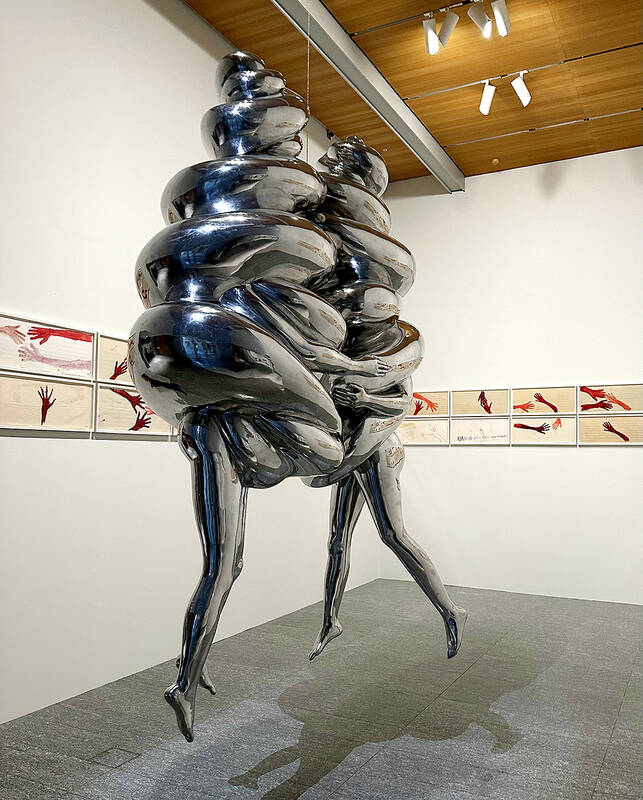

Upstairs, the final section of the exhibition opens into a vast room. Bourgeois’ later works invite reflection and healing.

Under a bright skylight, Arch of Hysteria (1993), a suspended bronze figure, arched in tension and release, captures the raw physicality of emotional suffering.

Across the room, gentle shades of blue wash over the sparse room, concluding Bourgeois’ psychoanalytic journey.

“I see her as one of the most incredible craftswomen, and the younger generation can learn much from her,” Manabu Yahagi says.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

Shunxian Temple (順賢宮) is luxurious. Massive, exquisitely ornamented, in pristine condition and yet varnished by the passing of time. General manager Huang Wen-jeng (黃文正) points to a ceiling in a little anteroom: a splendid painting of a tiger stares at us from above. Wherever you walk, his eyes seem riveted on you. “When you pray or when you tribute money, he is still there, looking at you,” he says. But the tiger isn’t threatening — indeed, it’s there to protect locals. Not that they may need it because Neimen District (內門) in Kaohsiung has a martial tradition dating back centuries. On