Parallels between Taiwan and Ukraine have been ubiquitous since Russia’s full-scale invasion of its neighbor in February 2023: small, vulnerable democracies in the shadow of authoritarian neighbors, targets of disinformation and hybrid attacks, bastions of civil society activism and resilience — today Ukraine, tomorrow Taiwan has been a refrain.

Yet one comparison that has received little attention is the punchiness that has plagued the countries’ two parliaments: the Legislative Yuan in Taiwan and the Verkhovna Rada in Ukraine.

This is understandable: Since the full-scale invasion, solidarity in Ukraine has affected domestic politics. And, as this book on legislative violence clarifies, relations with Russia influenced brawling among members of parliament (MPs) in Ukraine. Whether it was language, malign influence and corruption through Russia-friendly oligarchs or trade with the occupied territories since the 2014 annexation of Crimea, Moscow has long been a factor in parliamentary fisticuffs.

With Ukrainians of all stripes more united than at any time since the country’s independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, the absence of brawls from the Verkhovna Rada has been notable. The suspension of 11 pro-Russia parties in March 2022 doubtless helped. The last noteworthy scuffle in the Verkhovna Rada came during a 2020 wrangle over a land reform bill.

Nevertheless, any online greatest hits compilation of legislative brawls likely features Ukraine and Taiwan. Why have these two countries brawling found fertile field in each country?

Authors Nathan Batto, an associate research fellow at Academia Sinica — who offers outstanding insights into Taiwan’s electoral politics via his Frozen Garlic blog — and Emily Beaulieu, a University of Kentucky political scientist, who has published extensively on contentious politics, challenge arguments based on “cultural norms” or “predilections for violence.” The idea that brawls are “passionate outbursts” by “hot-headed fighter[s]” is rejected.

Instead, brawlers are almost always calculating individuals who have weighed the potential benefits and drawbacks of their actions, Batto and Beaulieu argue. They do not always get the cost-benefit analysis right, but because assessing such trade-offs is their bread and butter, they are adept “at judging how their target audiences and the wider public will react to a brawl and adjusting their behavior accordingly.”

It is true, the authors emphasize throughout the book, the electorate appears strongly averse to brawling, considering it unseemly, undemocratic and a stain on Taiwan’s reputation as a progressive democracy. However, key demographics may be won by such antics, depending on the political environment — particularly “the strength of the party system and the institutional context.”

SYSTEMIC INCENTIVES

The authors draw on signaling theory, which “seeks to explain behaviors in the absence of institutional oversight” to examine who is targeted by brawling legislators. The assumption is that individuals have an “underlying type” that others want to discern but cannot know for sure.

In a strong party system such as Taiwan’s, the target audience will generally be partisan and, “more specifically … whichever group wields a disproportionate influence over legislators careers, whether this be party leaders, rank-and-file party members or loyal party supporters in the electorate.”

The electoral system is crucial to which segment is targeted. For example, in a single nontransferable vote (SNTV) system, where multiple seats are available in a district and voters might choose between several candidates from the same party, brawling is incentivized as a way of standing out as a “loyal party soldier” to cultivate a personal voter base.

Until 2008, elections in Taiwan were held under SNTV rules, with no more than 21.8 percent of legislators chosen by closed list proportional representation (CLPR) at any election. Under a new mixed system of parallel voting, which saw the legislature halved to 113 seats, single-member plurality (SMP) — or first-past-the-post — rules replaced the SNTV, with CLPR legislators now elected by separate ballot.

COMMUNICATING TYPE

As SMP nominations are “highly decentralized” and, where contested, “typically determined by telephone surveys,” the target audience here is loyal party supporters. In contrast, with CLPR nominees determined by committees that are often steered by the party chair, the “payoffs [from brawling] for personal votes are much lower.”

In large legislatures such as those in Mexico and South Korea — from which cases studies are drawn for this book — legislators may be communicating to party leaders who are less likely to know them personally and, thus, their “type.”

However, this is likely less important in Taiwan, because of the smaller legislative caucuses. Indeed, the authors note that, in private interviews, politicians “repeatedly scoffed at” the idea that CLPR legislators needed to target leadership, insisting leaders “already knew their legislators quite well.”

Another factor is the possibility for consecutive re-election: In Mexico this was not permitted until 2018, meaning lawmakers had “no immediate legislative reputation to precede them,” and in South Korea it is “highly dependent on the whims of the party leader,” making brawling a more attractive tool for signaling to top brass.

At first glance, the data seemingly contradicts the authors’ expectations as to which legislators favor brawling in Taiwan, with SNTV lawmakers showing the lowest values on the “brawling intensity index.” However, when controlling for the fact that the data for SNTV legislators is from a period when there was far less brawling overall, the SNTV cohort comes top, followed by SMP lawmakers, with the CLPR portion revealing the lowest rates.

FIRST BLOOD

Rebutting scholarship that suggested brawling is more common among legislators from smaller, more extreme parties, Batto and Beaulieu argue that representatives from larger opposition parties are most likely to brawl. In Taiwan, historical circumstances played a role here, with lawmakers from the fledgling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) communicating their objection to the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) unjust rule in the early days of democratization.

Nicknamed “Rambo,” the late Ju Gau-jeng (朱高正) was emblematic of this breed of combative legislator who saw disruption and brawling as a necessary and even commendable tactic in the face of a rotten system.

While the political context in Ukraine is very different, with many smaller parties, less partisanship, and legislators flipping from parties, brawling is still revealed as a strategic decision.

Backed as they are by solid data, the arguments for brawling as a conscious choice are compelling, though some readers may feel that psychological, cultural and anthropological explanations for Taiwan’s legislative violence cannot be fully discounted.

Even so-called “honor brawlers” are analyzed as mostly communicating messages, often related to alleged corruption: In cases where the accusation — often itself a signal by the accuser — is considered a slur, a physical response emphasizes the impugned legislator’s probity; where the charges are leveled at figures with known criminal connections, violent retaliation staves off perceptions of weakness.

BOXING CLEVER?

One rather odd, peripheral argument concerns the lack of belligerence by former professional fighters-turned-politicians. Former heavyweight champion boxer Vitali Klitschko, the current mayor of Kyiv and an MP from 2012 to 2014, was never involved in brawls in the Verkhovna Rada, the authors observe. Likewise, during his three terms in the Legislative Yuan between 2004 and 2016, former KMT legislator Huang Chih-hsiung (黃志雄) did not showcase the skills that earned him taekwondo bronze and silver Olympic medals.

While recent studies challenge established view of boxing, in particular, as helping to assuage aggression, the idea that pugilistic prowess predisposes someone to brawling will be strange to afficionados of combat sports. Juxtaposing Klitschko, who like his younger brother and fellow champion Vladimir, holds a doctorate and was known for a calm, respectful demeanor during his career, with gangsters who have “a penchant for violence,” is a misplaced and rather unsavory touch.

As for stamping out the scourge of brawling: With the payoffs making it a rational albeit risky tactic, it is up to political elites to disincentivize violence, the authors conclude. In societies where social cleavages and identity politics fuel polarization, how this can be achieved remains unclear.

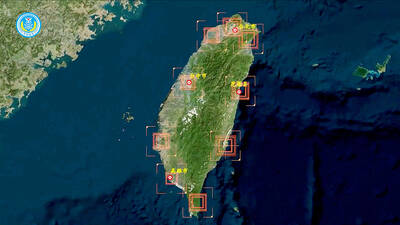

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

Shunxian Temple (順賢宮) is luxurious. Massive, exquisitely ornamented, in pristine condition and yet varnished by the passing of time. General manager Huang Wen-jeng (黃文正) points to a ceiling in a little anteroom: a splendid painting of a tiger stares at us from above. Wherever you walk, his eyes seem riveted on you. “When you pray or when you tribute money, he is still there, looking at you,” he says. But the tiger isn’t threatening — indeed, it’s there to protect locals. Not that they may need it because Neimen District (內門) in Kaohsiung has a martial tradition dating back centuries. On