For the past century, Changhua has existed in Taichung’s shadow. These days, Changhua City has a population of 223,000, compared to well over two million for the urban core of Taichung.

For most of the 1684-1895 period, when Taiwan belonged to the Qing Empire, the position was reversed. Changhua County covered much of what’s now Taichung and even part of modern-day Miaoli County. This prominence is why the county seat has one of Taiwan’s most impressive Confucius temples (founded in 1726) and appeals strongly to history enthusiasts.

This article looks at a trio of shrines in Changhua City that few sightseers visit. None is especially well known, and one isn’t currently open to the public. Yet all three places of worship offer something more than the usual McTemple.

Photo: Steven Crook

HAILED AS A KING

What bilingual signs call the Sheng King Temple (聖王廟) is a national-level relic hidden in the back streets at 19, Lane 239, Zhonghua Road (中華路). Established in 1732 (some sources say 1761), it was founded to honor a deified Guangdong native who was known in his lifetime as Chen Yuan-guang (陳元光).

Remembered for his wise governance at the start of the eighth century, Chen was revered by the inhabitants of Zhangzhou (漳州) in China’s Fujian Province and their descendants in Taiwan. As Sheng King, he’s worshiped in at least a dozen other temples around the country, most of them being in the south and all of them in locations associated with settlement by Zhangzhou people.

Photo: Steven Crook

In addition to the monarch himself, represented by a clay effigy, Changhua’s Sheng King Temple enshrines the king’s wife in the rear hall, as well as a pair of eunuch servants.

The front of the building is flanked by hefty yet finely-carved dragon and tiger reliefs. The door gods are appealingly timeworn. It’s recorded that craftsmen brought in from Guangdong were responsible for certain distinctly Cantonese design elements. But I’ve not been able to discover what those features might be.

VIRTUE AND PIETY

Photo: Steven Crook

Several years ago, I was fortunate to stumble across entirely by accident what the few English-language sources variously call Jie Xiao Temple (節孝祠) or the Shrine to Virtue and Piety. What’s more, I happened to be there on one of the two days each week that it was open to the public. Right now there’s no way tourists can see its delightfully antiquated interior. That’s a pity as this temple has an unusual purpose.

When I looked around, I noticed several strips of colored papers taped to the floor; my best guess is that they were there to tell ritual participants where to stand. In addition to the usual incense and fruit, cosmetics were among the items on the offertory table — which made sense when I learned that the temple exists to provide posthumous support to certain people otherwise excluded from the traditional system of ancestor worship.

According to Han concepts of filial piety, girls are outsiders in their birth family, because they’re destined to marry, join their husband’s family and take care of his parents. As a result, women who don’t marry have no place in an ancestor cult, nor any relatives who can look after them in their dotage. (This is why some families will arrange a “ghost wedding” for a female who died without ever marrying.)

Photo: Steven Crook

Shrines like Jie Xiao Temple aimed to plug this gap, but only for certain, deserving women. During the 1870s and 1880s, local literati identified 160 “chaste women” (in other words, females who’d never married) whose exemplary behavior entitled them to better treatment.

Following expressions of support by local officials and permission from the Ministry of Rites in Beijing, the shrine was inaugurated in 1888, with names being added to it as recently as 1924. The current structure dates from 1923, when the colonial government’s insistence of widening some of Changhua’s roads resulted it being dismantled and reassembled at the foot of Mount Bagua (八卦山). The address is 51 Gongyuan Road Sect. 1 (公園路一段).

While a few other halls of worship provide a similar service, Jie Xiao Temple is the country’s only standalone shrine devoted to deceased unmarried women. That said, in recent years at least one notable lineage in Taiwan has broken with ancient tradition and decreed that females can be worshipped at the same altar as their parents and brothers.

Photo: Steven Crook

HELL ON EARTH

The popular religion that many Taiwanese practice isn’t the only faith that keeps some people on the straight and narrow by scaring them witless. Over thousands of years, the belief that you’ll be made to pay in the next world for misdeeds committed in this one has evolved into an elaborate structure with “Ten Courts” (in which the recently dead are judged) and “Eighteen Levels” (where punishments are meted out).

In recent decades, at least two temples in Taiwan have embraced technology to reinforce traditional (and quite graphic) visual depictions of what Mandarin speakers call diyu (地獄). One is Madou Daitian Temple (麻豆代天府) in Tainan (see “Disappeared sea and a side trip to hell” in the Dec. 18, 2020 issue of this newspaper). Another is Changhua’s Nantian Temple (南天宮), a few hundred meters due south of the highest part of Mount Bagua (八卦山) at 12, Lane 187, Gongyuan Road (公園路) Section 1.

The latter temple’s 18 Levels of Hell (十八層地獄) is open from 8am to 6:30pm. Admission is NT$50 — and I received a real fright as soon as I stepped inside, though probably not in the way the designers had intended.

Following the signs into a dark corridor, for a moment I thought the floor was collapsing under me. I then realized this was a hydraulic pressure pad. As it made an evil-sounding hiss, a few lights came on and the soundtrack began playing.

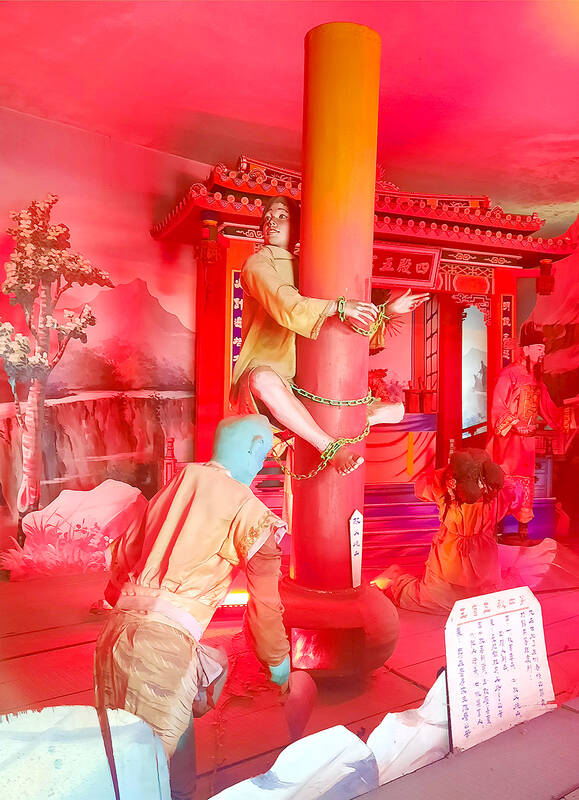

Unlike at Madou Daitian Temple, there’s no English-language explanation of what you’re seeing. Nevertheless, the parade of hapless souls being tortured by demons is tackily entertaining.

Shuddering animatronic figures (a few of which are clearly malfunctioning) gleefully inflict pain. One wrongdoer is crushed beneath the wheels of a cart driven by a blue-skinned demon. Another is fried in a wok. Others are condemned to freezing conditions, hung upside-down by their entrails, or hurled onto sharpened stakes. One devil rides a seesaw-like contraption so as to pulverize a miscreant.

The head of one ghoul repeatedly rises above then returns to his shoulders. I spent a good while looking at him, because his jacket and cravat made me think of Chen Cheng-bo (陳澄波), the painter who was murdered in the wake of the 228 Incident.

The only other visitors I saw were a young couple. I thought to myself: If your girlfriend is happy to go on a date to this kind of place, she’s a keeper.

When Nantian Temple’s management committee decided to invest in this oddity, what were they hoping for? That it might drum home a key message? Or that it’d bring visitors and revenue to an otherwise obscure place of worship? Whatever their intentions, nowadays the 18 Levels of Hell seems to be merely a place where people go to for something a bit out of the ordinary and for half an hour of inexpensive amusement.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by