This is a strange book. I wanted to like it: I know the author, have attended several excellent talks that he has hosted at his cafe and event space Daybreak, and respect his activism and contribution to communicating Taiwan to the world in a way that was lacking until he cofounded New Bloom magazine in 2014.

Through this vehicle, Brian Hioe has tirelessly advocated for the rights of minorities and the disenfranchised, called out injustices and inequalities, past and present, and pushed back against democratic backsliding.

In articles for The Diplomat, he has introduced Taiwan’s politics and society to a wider audience, making it palatable for the uninitiated, steering clear of the usual cliches that define the country through its relations with China, and affording it an agency invariably absent from international reports.

At public events, he demonstrates erudition, eloquence and a keen intellect. I’ve not left any of the Daybreak discussions without having learned something — usually quite a lot (including a load of new conceptual and theoretical terminology!).

Yet, the passion the drives this work is largely absent from these pages. The narrator, QQ, who Hioe has described as a fictionalized version of himself, based on his experiences as an activist during the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement in New York and the 2014 Sunflower movement, has almost no redeeming attributes.

On the back cover and inside pages, a quote from Shawna Yang Ryan, author of the White Terror-focused novel Green Island, compares Hioe’s novel stylistically to the works of Camus and Dostoevsky. While this is quite a reach, there are perhaps tenuous similarities — the sparse prose and depiction of a tortured soul searching for meaning through action.

Yet, unlike Camus’ Meursault, whose sensuality and casual rejection of social norms has visceral appeal, or Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, whose moral conundrum and theorizing about the “extraordinary man,” fascinates, there is little about QQ for a reader to latch on to. He is a not even an antihero.

ACTION, APATHY AND ALIENATION

As creeping nihilism takes hold, QQ perhaps better recalls the superfluous men of Russian literature — Pechorin, the fatalistic hero of Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time or, at times, as QQ festers in his “windowless box,” where “the outside world had ceased to exist or might never have existed,” — the listless title character Oblamov in Goncharov’s classic study of inaction.

Of course, unlike the affable Oblamov, QQ is not completely paralyzed by apathy — he is, or sees himself as, very much a man of action. It is through his participation in social movements, protests and increasingly the prospect of violence that he comes to define himself.

At a recent discussion of his book at Daybreak (the event space), Hioe noted that social movements often attract participants with emotional and mental health issues.

“You encounter a lot of people that are quite alienated,” he said.

Still, for all the emphasis on the existentialist credo of being as doing, the scenes depicting concrete action — the March 18, 2014 assault on the Legislative Yuan and a week later the storming of the Executive Yuan during the Sunflower protests, and the occupation of the Ministry of Education grounds in July 2015 — are distinctly underwhelming.

A NEW DAWN

Upon receiving news of the initial “318” occupation of the legislature, QQ is strangely “dismissive,” and “cynical,” suspecting the protesters will quickly be dislodged. The news is insufficiently important to interrupt dinner with a friend. Then, having “got antsy,” the narrator declares himself “never one to pass up a chance for action,” and “decide[s] to take a gamble.”

It all comes across as contradictory and half-hearted. Outside the legislature, he admits that he “hung around at the back” for fear of arrest, while others “grew more and more brazen.” Instead of joining the vanguard, QQ lingers sheepishly on the periphery, checking social media for updates from those inside the building. Eventually, propping his head against a vehicle in a carpark, he begins to snooze.

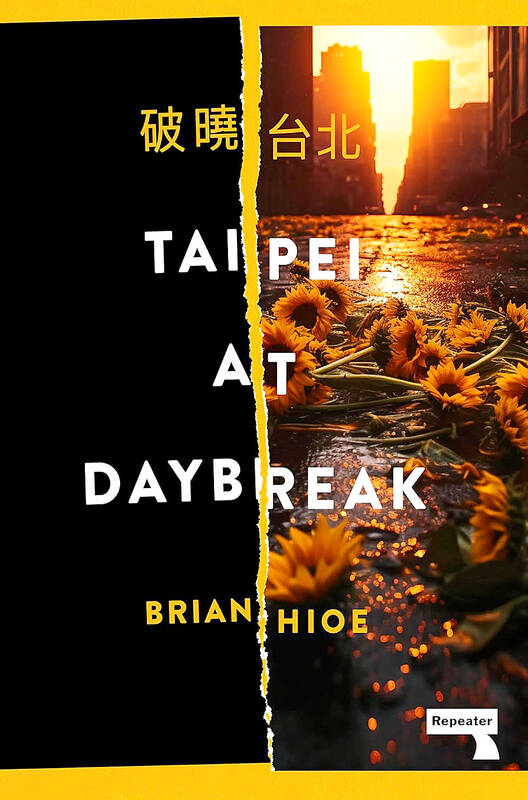

It’s true, the image of sunflowers being clasped and waved by the protesters at dawn, as QQ drifts in and out of slumber, is an appealing symbol of hope. Hioe has attributed the name of the Daybreak Project — an oral history archive of the movement, which can be found at the New Bloom Web site, his cafe/event space and the book’s title to this awakening and the promise of change brought by Taiwan’s young activists.

VIOLENT FANTASIESM

In this image, we have something of a counterpoint to the protagonist’s misanthropy and his trajectory toward self-destruction. Punctuated by cryptic and increasingly unhinged interpolations from a one-way conversation with an unknown individual dubbed “V,” the protagonist’s reflections hint at dissociation.

While QQ is more hands-on during the “324” attempt to occupy the Executive Yuan, joining the throng to push back the riot-shielded police, he still ends up “ejected from the center of the charge” where he “assumed a look of not really understanding what I was doing,” seemingly to protect himself from the police batons.

Later, he joins a group of people lying on the ground to prevent the police from cutting through the encirclement of protesters, alongside an activist comrade who sobs at the brutality of it all, before things gradually fizzle out.

At the 2015 education ministry protest, sparked by the then-Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) government’s proposed changes to the high school curriculum and the suicide of student activist Lin Kuan-hua (林冠華), QQ approaches the stage where a local mobster (the Grey [sic] Wolf in Hioe’s telling), is haranguing the students with anti-Japanese slogans.

Although the gangster — a depiction of real-life organized crime figure and fringe pro-China politician Chang An-lo (張安樂), who is nicknamed the White Wolf — is surrounded by his goons, QQ fantasizes about dragging him from the stage and breaking his neck.

“I didn’t have this black belt for nothing, not that it had ever been useful,” he says — again seeming to contradict himself.

MISSED OPPORTUNITY

Like many of his thoughts, statements and actions, this throwaway revelation of pugilistic prowess, of which there is no previous indication, comes across as empty bravado, especially when, predictably, he just slinks off into the crowd.

A sudden reference to bouts of booze-fueled aggression after consuming “the entirety of a small bottle of whiskey” is similarly unconvincing, as are attempts to communicate the danger he and his comrades face during the various incidents.

Even the one scene where he actually does something dangerous and genuinely violent — smacking a friend in the gob — seems tacked on and implausible.

Perhaps this is deliberate: This “Asian American coming of age novel,” as the back cover blurb has it, aims to show a young, conflicted soul desperate to prove himself and be a part of something. Expressing his envy of a fellow activist, he admits, “I had never been willing to take such risks for things I believed in.”

Still, it all makes for a frustratingly hollow reading experience and not because of the “emptiness,” that QQ refers to when addressing V.

Here and there, glimmers of something more profound emerge: ruminations on Asian American identity — QQ’s description of himself as the gap in the text between the words “Taiwanese” and “American” providing a memorable metaphor.

But with such an unsympathetic lead and supporting characters flitting in and out, with rarely enough to them to make you care, this feels like a missed opportunity to render a pivotal moment in contemporary Taiwanese history through a literary medium.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of