More than 100,000 people were killed in a single night 80 years ago yesterday in the US firebombing of Tokyo, the Japanese capital. The attack, made with conventional bombs, destroyed downtown Tokyo and filled the streets with heaps of charred bodies.

The damage was comparable to the atomic bombings a few months later in August 1945, but unlike those attacks, the Japanese government has not provided aid to victims and the events of that day have largely been ignored or forgotten.

Elderly survivors are making a last-ditch effort to tell their stories and push for financial assistance and recognition. Some are speaking out for the first time, trying to tell a younger generation about their lessons.

Photo: AFP

Shizuyo Takeuchi, 94, says her mission is to keep telling the history she witnessed at 14, speaking out on behalf of those who died.

RED SKIES, CHARRED BODIES

On the night of March 10, 1945, hundreds of B-29s raided Tokyo, dumping cluster bombs with napalm specially designed with sticky oil to destroy traditional Japanese-style wood and paper homes in the crowded shitamachi downtown neighborhoods.

Photo: AFP

Takeuchi and her parents had lost their own home in an earlier firebombing in February and were taking shelter at a relative’s riverside home. Her father insisted on crossing the river in the opposite direction from where the crowds were headed, a decision that saved the family. Takeuchi remembers walking through the night beneath a red sky. Orange sunsets and sirens still make her uncomfortable.

By the next morning, everything had burned. Two blackened figures caught her eyes. Taking a closer look, she realized one was a woman and what looked like a lump of coal at her side was her baby.

“I was terribly shocked. ... I felt sorry for them,” she said. “But after seeing so many others I was emotionless in the end.”

Photo: AFP

Many of those who didn’t burn to death quickly jumped into the Sumida River and were crushed or drowned.

More than 105,000 people were estimated to have died that night. A million others became homeless. The death toll exceeds those killed in the Aug. 9, 1945, atomic bombing of Nagasaki.

But the Tokyo firebombing has been largely eclipsed by the two atomic bombings. And firebombings on dozens of other Japanese cities have received even less attention.

The bombing came after the collapse of Japanese air and naval defenses following the U.S. capture of a string of former Japanese strongholds in the Pacific that allowed B-29 Superfortress bombers to easily hit Japan’s main islands. There was growing frustration in the United States at the length of the war and past Japanese military atrocities, such as the Bataan Death March.

RECORDING SURVIVOR’S VOICES

Ai Saotome has a house full of notes, photos and other material her father left behind when he died at age 90 in 2022. Her father, Katsumoto Saotome, was an award-winning writer and a Tokyo firebombing survivor. He gathered accounts of his peers to raise awareness of the civilian deaths and the importance of peace.

Saotome says the sense of urgency that her father and other survivors felt is not shared among younger generations.

Though her father published books on the Tokyo firebombing and its victims, going through his raw material gave her new perspectives and an awareness of Japan’s aggression during the war.

She is digitalizing the material at the Center of the Tokyo Raids and War Damage, a museum her father opened in 2002 after collecting records and artifacts about the attack.

“Our generation doesn’t know much about (the survivors’) experience, but at least we can hear their stories and record their voices,” she said. “That’s the responsibility of our generation.”

“In about 10 years, when we have a world where nobody remembers anything (about this), I hope these documents and records can help,” Saotome says.

DEMANDS FOR FINANCIAL HELP

Postwar governments have provided 60 trillion yen (US$405 billion) in welfare support for military veterans and bereaved families, and medical support for survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Civilian victims of the US firebombings received nothing.

A group of survivors who want government recognition of their suffering and financial help met earlier this month, renewing their demands.

No government agency handles civilian survivors or keeps their records. Japanese courts rejected their compensation demands of 11 million yen (US$74,300) each, saying citizens were supposed to endure suffering in emergencies like war. A group of lawmakers in 2020 compiled a draft proposal of a half million-yen (US$3,380 ) one-time payment, but the plan has stalled due to opposition from some ruling party members.

“This year will be our last chance,” Yumi Yoshida, who lost her parents and sister in the bombing, said at a meeting, referring to the 80th anniversary of Japan’s WWII defeat.

BURNT SKIN AND SCREAMS

On March 10, 1945, Reiko Muto, a former nurse, was on her bed still wearing her uniform and shoes. Muto leapt up when she heard air raid sirens and rushed to the pediatric department where she was a student nurse. With elevators stopped because of the raid, she went up and down a dimly lit stairwell carrying infants to a basement gym for shelter.

Soon, truckloads of people started to arrive. They were taken to the basement and lined up “like tuna fish at a market.” Many had serious burns and were crying and begging for water. The screaming and the smell of burned skin stayed with her for a long time.

Comforting them was the best she could do because of a shortage of medical supplies.

When the war ended five months later, on Aug. 15, she immediately thought: No more firebombing meant that she could leave the lights on. She finished her studies and worked as a nurse to help children and teenagers.

“What we went through should never be repeated,” she says.

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

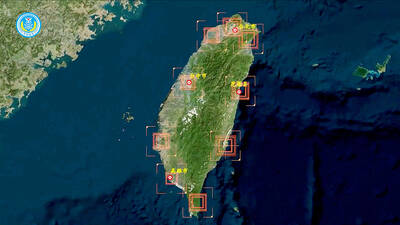

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,