This review has to begin with a confession and a disclosure.

I’m no fan of Taiwanese teas. I don’t think I’ve ever drunk one that I’d go out of my way to buy. Oolong zealots — and I’ve met a good few — have singularly failed to convert me.

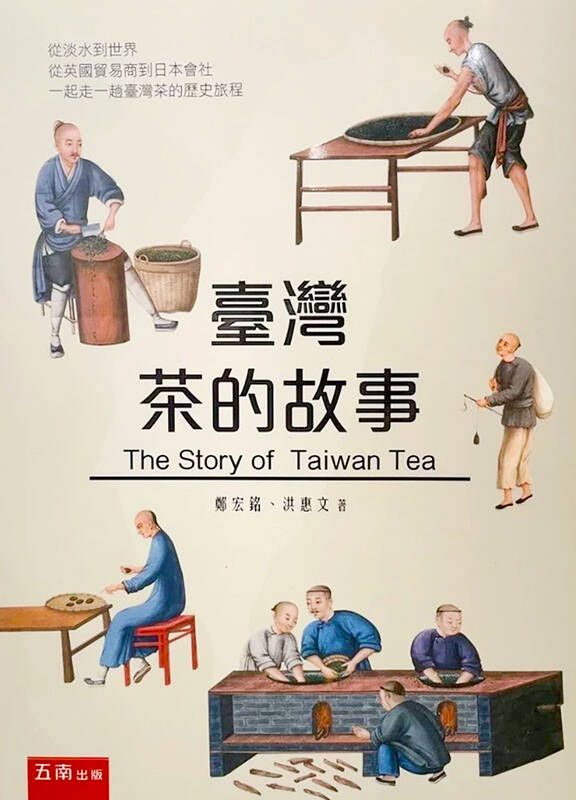

One of this book’s co-authors, Katy Hui-wen Hung (洪惠文), is an occasional collaborator of mine; we’ve written a book and several articles together. The other, Hong-ming “HM” Cheng (鄭宏銘), is well known among English-speaking aficionados of Taiwan history on account of “The Battle of Fisherman’s Wharf,” a blog where he compiled hundreds of fascinating stories between 2009 and 2019.

When Hung and I were putting our book together, Cheng was a key source of facts and anecdotes. Accordingly, I picked up this attractive bilingual volume with every expectation it’d be carefully researched and filled with engrossing details, and I wasn’t disappointed.

The 15 chapters in the English-language section (pages 163—272) mirror the Chinese-language content. In order to cram everything in, the publisher opted for a font size so small some readers may find it a problem. This is one distraction; others are weird shifts from one typeface to another, repetitive phrasing and some inconsistencies when it comes to people’s names.

In the space of two pages, we’re told again and again that tea-processing knowledge in China was “closely guarded.” And, just in case you forget, there are frequent reminders that tea leaves require “meticulous” picking and handling.

The wife of Canadian missionary George Mackay is referred to as “Mini,” yet most sources spell her English name “Minnie.” Within two paragraphs on page 198, we’re presented with three different spellings of Zheng Jing (鄭經). Inexplicably, Taiwanese-American botanist Shang Fa Yang (楊祥發, 1932-2007) has his name rendered according to hanyu pinyin.

Zheng’s father, Koxinga (鄭成功) didn’t capture the Dutch East India Company’s Fort Zeelandia (in modern-day Tainan) in 1661, as the book states, but the following year after a long siege. In an otherwise fascinating explanation of how Portugal was overtaken by the Dutch and the British as the leading supplier of tea to Europe, the assertion that “In 1680, Portugal lost its monopoly over Macao to the Qing dynasty,” is misleading on two counts. Nothing happened until 1684-85, when the Qing court began allowing foreign traders to enter Canton and a few other ports, and Portugal’s control over Macao wasn’t in any way diminished.

Despite these gripes, Taiwan obsessives — I can’t speak for tea drinkers — will find The Story of Taiwan Tea a worthwhile addition to their bookshelf, and not just because it’s very possibly the first book-length English-language exploration of its subject.

The authors share some obscure yet delightful nuggets of history, several of which have nothing whatsoever to do with tea.

Following his surrender to the Qing dynasty in 1683, Zheng Jing’s son, Zheng Ke-shuang (鄭克塽), was given safe passage to Beijing on condition that he and his direct descendants never leave the imperial capital; this restriction applied until the fall of the last Qing emperor in 1911 (after which, according to Wikipedia, they “moved back” to Fujian).

A Massachusetts-based dealer in Taiwanese oolong called Charles Arshowe (翁阿紹) became in 1860 the first Chinese person to be naturalized as a US citizen. Kabayama Sukenori, later Japan’s first governor-general of Taiwan, visited the island in 1873 to gather intelligence, disguised as a mute Buddhist monk.

As you might expect, an entire chapter is given over to the pioneering tea traders John Dodd of England and Fujian-born Li Chun-sheng (李春生). Dodd was based in New Taipei City’s Tamsui, a town with which both authors have strong ancestral ties, and the following chapter examines connections between the tea trade and Tamsui’s temples.

Chapter 6 summarizes Robert Fortune’s famously audacious missions that resulted in the British East India Company usurping China’s position as the world’s dominant producer of tea. I didn’t know that Fortune — whose name can be a two-word response to claims that China is always the villain when it comes to IP theft — visited Tamsui circa 1853 to look into the commercial potential of the area’s abundant rice-paper plants (a species unrelated to rice or, for that matter, tea).

One of this book’s strengths is that it doesn’t look merely into the past. The penultimate chapter speculates as to how emerging CRISPR-Cas9 genome-editing techniques could be used to enhance the taste, nutritional content and disease resistance of teas. And, helpfully for those who don’t stay abreast of scientific breakthroughs, it begins by explaining what CRISPR is.

The final chapter is a broader discussion of the future of locally-grown teas, and the authors make several suggestions as to how tea might be able to regain some of the ground it’s lost to coffee over the past few decades. But there’s no need to read The Story of Taiwan Tea from front to back. Quite a few people, I expect, will dip into this book. For that reason, an index would have been a useful addition.

I’m sure I’ll return to the section on the potential health benefits and health risks of tea consumption, which follows a surprisingly accessible deep-dive into the chemistry behind tea flavors. Given Cheng’s background — he’s an ophthalmologist who’s taught at Harvard University — I’m inclined to believe every carefully-chosen word. But I doubt it’ll be enough to get me to drink oolong on a regular basis.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Last week the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) said that the budget cuts voted for by the China-aligned parties in the legislature, are intended to force the DPP to hike electricity rates. The public would then blame it for the rate hike. It’s fairly clear that the first part of that is correct. Slashing the budget of state-run Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) is a move intended to cause discontent with the DPP when electricity rates go up. Taipower’s debt, NT$422.9 billion (US$12.78 billion), is one of the numerous permanent crises created by the nation’s construction-industrial state and the developmentalist mentality it

Experts say that the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on Friday was likely the strongest to hit the country in decades, with disaster modeling suggesting thousands could be dead. Automatic assessments from the US Geological Survey (USGS) said the shallow 7.7-magnitude quake northwest of the central Myanmar city of Sagaing triggered a red alert for shaking-related fatalities and economic losses. “High casualties and extensive damage are probable and the disaster is likely widespread,” it said, locating the epicentre near the central Myanmar city of Mandalay, home to more than a million people. Myanmar’s ruling junta said on Saturday morning that the number killed had