From censoring “poisonous books” to banning “poisonous languages,” the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) tried hard to stamp out anything that might conflict with its agenda during its almost 40 years of martial law.

To mark 228 Peace Memorial Day, which commemorates the anti-government uprising in 1947, which was violently suppressed, I visited two exhibitions detailing censorship in Taiwan: “Silenced Pages” (禁書時代) at the National 228 Memorial Museum and “Mandarin Monopoly?!” (請說國語) at the National Human Rights Museum.

In both cases, the authorities framed their targets as “evils that would threaten social mores, national stability and their anti-communist cause, justifying their actions under what they called a free and democratic state.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

In reality, what was banned often came down to the whims of those in charge: “The people could never predict when the great sword of censorship would drop, they could only keep guessing the thoughts of the authorities,” a display states.

“Teacher, why didn’t he get hit for speaking Cantonese?” reads a poem by Lim Chong-goan (林宗源) in the Mandarin policy exhibition. “Teacher, why wasn’t he fined for speaking English? The teacher then grabbed the bamboo stick and smashed my heart.”

FORBIDDEN TOMES

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

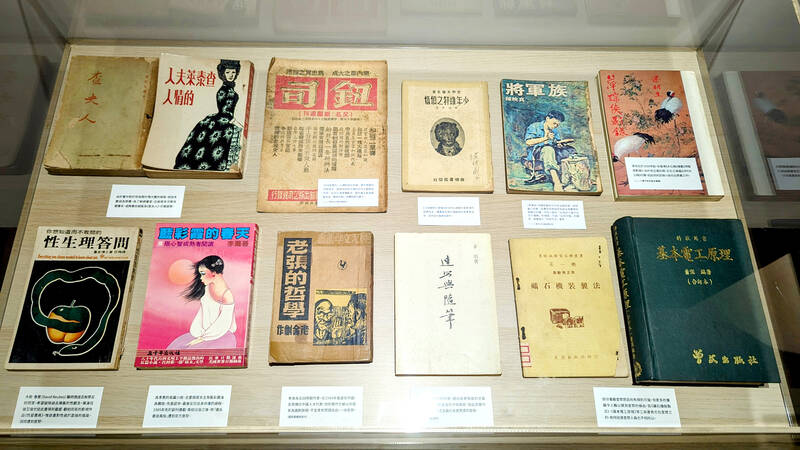

Even for someone like me who has done extensive research on censorship, the scope of the bans is still jarring. Leftist, erotic and anti-government titles are obvious, but martial arts novels, machinery textbooks — and the dictionary?

Opening last Friday, this new exhibition offers a comprehensive look at how the authorities suppressed publishing freedom and those who paid the price for reading banned material.

While the introductory text and section headers are translated into English, the rest of the display is entirely in Chinese. This has been a continued gripe of mine at this national-level institution. That being said, Google Translate’s Lens feature does an adequate job — it’s even able to translate some handwritten documents.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

The first part lays out the legal basis for censorship as well as the influence a single Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) committee had over what was allowed to be published. Needless to say, any mention of the 228 Incident was taboo until the 1980s.

The Cultural Purity Movement in 1954 targeted people deemed “red” (leftist), “yellow” (sexual) and “black” (exposing government secrets), but the actual standards were much looser. Indeed, anything that the government didn’t agree with politically or deemed immoral and harmful to society could be banned — including a book on how to pick up women using English. The popular martial arts novels by Jin Yong (金庸) were also prohibited, presumably due to the characters’ defiance of authority.

Dictionaries and car manuals were struck down if the writer remained in China after the Chinese Civil War. Even the German novel The Sorrows of Young Werther was targeted because the translator was a leftist.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“Unless you lock people inside a small world and forbid them from any outside contact, these methods will not work,” wrote Free China magazine in 1956.

Taiwanese continued to be arrested for speaking out against the policy or reading illegal books, but publishers always found ways to circumvent the censors. Still, many writers remained silent, hiding their manuscripts or abandoning writing altogether.

It’s a solid, informative exhibit, one that could be made better if the museum expanded the small banned books library section into a regular feature and keep adding to the list.

Those who don’t read Chinese might want to give it a pass, though it’s worth a visit if seen in conjunction with the excellent permanent installation and other exhibits, including The Spectre of Freedom: Art of Resistance featuring the work of Hungarian artist Steven Balogh.

SILENCED TONGUES

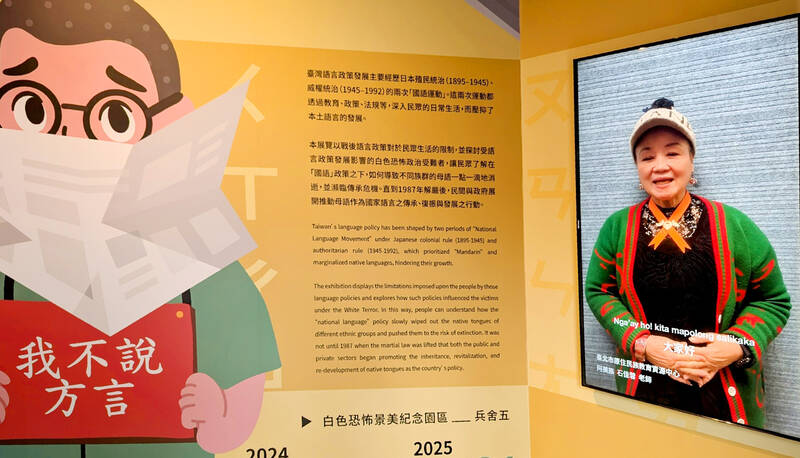

“Mandarin Monopoly?!”, on the other hand, is fully translated into English. Visitors are welcomed by a video screen of people speaking Paiwan, Atayal, Amis, Hakka and Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese), a reminder that the nation’s various languages persevered despite KMT censorship.

However, the damage to some of the nation’s other languages is irreversible. It’s one thing to reprint banned books, but it’s much harder to get people to start speaking their once-banned languages, especially indigenous languages, again.

The exhibition notes the Japanese also banned local languages and publishing in Chinese after 1937, rewarding families who primarily spoke Japanese at home. After the war, these families suddenly were barred from using Japanese, and were forced to learn Mandarin.

A selection of writings by political prisoners in this early period of KMT rule shows the struggle people had with this new language, including a written request by Huang Lung-sheng (黃龍勝) to have a Hakka-speaking judge translate during his trial, and a letter by White Terror victim Uyongu Yatauyungana detailing to his family how difficult it was to write in Chinese — he had to dictate it in Japanese to a fellow prisoner, who translated it into Chinese then transcribed it.

A significant part of this exhibition covers the punishments levied on those who broke the rules. Even speaking Mandarin with a Taiwanese accent was considered backwards and vulgar compared to regional Chinese accents spoken by immigrants fleeing the Chinese Civil War.

“After I grew up, I asked my parents why they didn’t teach me the language of our people,” writes indigenous Truku author Apyang Imiq. “Mother replied, why do you blame me? When I spoke our language at school I had to wear a sign around my neck. Father replied, why do you blame me? When I spoke our language in the army, I was slapped by the sergeant, who said I was speaking the devil’s tongue to confuse others.”

As with banned books, people still found ways to preserve their language, and in the 1980s activists began fighting to reclaim their endangered heritage. At the end of this excellent, well-thought out exhibition, visitors are encouraged to leave a message in their mother tongue for others to hear. I recorded mine in Cantonese.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern