It was only a matter of time before US President Donald Trump set his sights on Taiwan. Based on his congratulatory phone call to former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) after her return to power in 2020, the more optimistic among us might have hope for continued support.

Alas, Trump 2.0 is a proposition that has taken even the most canny and cynical of observers by surprise with the aggression he and his administration have shown toward traditional allies. Following threatened tariffs against Canada and Mexico and hints of the same against Europe, Trump raised the prospect of trade sanctions against Taiwan, which he accused of stealing US microprocessor know-how.

“Taiwan took our chip business away,” Trump told a press conference on Feb. 13. He followed this up with a threat of 100 percent duties on chips from Taiwan “if they don’t bring it back.”

To anyone who had been listening to his campaign pledges, it shouldn’t have been a bombshell. In July last year, Trump had told Bloomberg that Taiwan stole the US’ chip manufacturing industry, that Taipei gave America nothing and that, as such, it should pay Washington for defense just like “an insurance policy.”

Economists and industry experts quickly pointed to the impracticalities of Trump’s strategy, arguing that hitting Taiwan with exorbitant tariffs would simply drive high-end chip prices up, with US consumers footing the bill. The idea that this was would suddenly drive reshoring was also dismissed, with the five-year lead time on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC) first Arizona fab, set to open this year, offered as an example of how long these things take, and the obvious issues of labor costs highlighted.

Elsewhere, Trump’s critics charged that the president betrayed a fundamental misunderstanding of how the semiconductor industry works: The US, they explained, was largely responsible for chip design, while Taiwan focused on manufacturing. President William Lai (賴清德) echoed these remarks, calling the industry an “ecosystem” which relied on a division of labor.

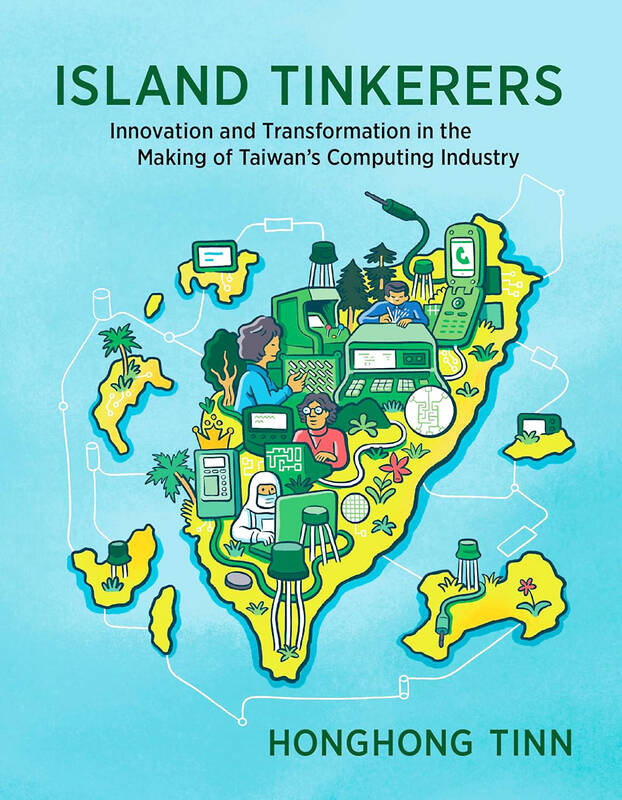

In response, Trump might argue that this was not always so. As Honghong Tinn (鄭芳芳) writes in this engrossing and meticulously researched new book, it wasn’t until 1987, when Morris Chang (張忠謀) founded TSMC as the world’s first dedicated or pure-play foundry, that these distinct roles emerged. Prior to that, leading US technology companies, such as Intel, IBM and Texas Instruments and Asian giants such as Samsung and Toshiba had been integrated device manufacturers, handling all aspects of chip design and fabrication.

REPLICATING SUCCESS

The dedicated foundry model, which Tinn notes may have been pilfered from then-UMC chairman Robert Tsao (曹興誠), who had previously consulted Chang about the feasibility of such an undertaking, was established after Taiwan’s “godfather of technology” minister without portfolio Li Kwo-ting (李國鼎) persuaded Chang to relocate to Taiwan to head the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI).

Unlike most of the technologists featured in this book, Chang had never previously lived in Taiwan but “had shaped Taiwan’s electronics industry in a substantive manner” as an informal advisor to the government on technology transfer projects, establishment of manufacturing facilities, and subcontracting work for Texas Instruments and, later, General Instrument.

Chang and Tsao’s hunch that dedicated foundries were the way forward for Taiwan was based on several considerations, including the belief that the tinkering-based know-how that had brought Taiwan’s researchers, engineers and technicians success in computer manufacturing could be replicated in the production of integrated circuits (ICs). Another prediction was that IC demand would soon explode, leading electronics companies that lacked the requisite expertise to outsource production.

In such an environment, large-scale manufacturers would thrive, Chang believed. He was also inspired by Introduction to VLSI System, a legendary textbook by a pair of American computer scientists that is credited with spawning the IC design industry and the division with manufacturing.

MISSING THE BOAT

More evidence that all of this started before America needed making great again, the Magadonians will insist. Perhaps. But, leaving aside the issues of legitimate technology transfer through official cooperation, the emergence of transnational supply chains, and the legions of US-educated Taiwanese- and Chinese-Americans who moved seamlessly between countries and institutions, a key point missed by those who cry theft is that the US big guns were invited in from the get-go, but declined.

In fact, on trips to the US to raise seed money, Chang failed to get a hearing with most companies who considered his proposal “unfeasible.” The two that did receive his pitch — Intel and Texas Instruments — politely declined. In the end, Dutch multinational Philips was the sole foreign investor with 27.5 percent of the startup capital.

True, Intel did soon send personnel to Taiwan to finesse TSMC’s processes with a view to eventually having them subcontract. This began with “leftover” contracts but, with Intel soon unable to fulfil orders, quickly became an official “qualified” independent contractor arrangement. By the mid-1990s, most of TSMC’s sales were to fabless design firms.

But all of this misses the point: Trump’s playbook on how to lose friends and alienate people tramples all over a relationship that was and continues to be founded on mutual benefit.

‘ASPIRATIONAL TINKERERS’

Tracing the history of Taiwanese tinkering to National Chiao Tung University (NCTU) alumni who pushed for the re-establishment of the institution in Taiwan, Tinn not only contradicts received wisdom about top-down processes, but she also shows how this was a transnational process from the start.

To be sure, officials played a role, with vice minister of communications Chien Chi-chen (錢其琛) pushing the bid for technical assistance under a United Nations Special Program — the kind of fruitful cooperation that Trump and his enforcer Elon Musk are currently attempting to end.

In her conclusion, Tinn uses the example of a US high school team comprising undocumented immigrants which bested a group of MIT grads in a robot design competition to highlight what “aspirational tinkerers” can achieve.

Chien and other early technologists cunningly secured government approval by tying the field of electrical engineering to atomic energy — an obsession of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣中正) and his Chinese Nationalist Party government.

There are, Tinn notes in her conclusion, clear parallels with the way Taiwan’s contemporary technologists have made their products indispensable — not only to their own national defense but to that of the US and, indeed, the world. Trump would do well to remember where some of the specialized chips used in American fighter jets are sourced.

Aside from pragmatic concerns, something more affecting, more essential permeates the pages of this remarkable story: the close personal bonds that were formed between generations of innovators that form the book’s dramatic personae.

Recalling fondly his time as training at an electronics factory in Watseka, Illinois, in the 1960s, Bruce C.H. Cheng (鄭崇華) — who would later found Delta Electronics — was struck by the camaraderie he was shown.

His American coworkers were aware that their company was poised to establish a Taiwan facility, jeopardizing their own livelihoods. Joking that they would be hastening their redundancy if Cheng learned too fast, they nevertheless took him under their wing.

“[They] remained enthusiastic about teaching Cheng and his fellow Taiwanese colleagues every part of the production,” writes Tinn, “and they generously took turns inviting Cheng and others to each of their homes.”

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern