In the mess hall of a Canadian military base a few hundred kilometers south of the Arctic Circle, Brigadier-General Daniel Riviere pointed to a map highlighting the region that is becoming a national priority.

“All eyes are on the Arctic today,” said Riviere, who heads the Canadian Armed Forces Joint Task Force North.

Thawing ice caused by climate change is opening up the Arctic and creating access to oil and gas resources, in addition to minerals and fish. That has created a new strategic reality for Canada, as nations with Arctic borders like the US and Russia intensify their focus on the region.

Photo: AFP

China, which is not an Arctic power, sees the area as “a new crossroads of the world,” the US warned in the final weeks of president Joe Biden’s administration. Ottawa has responded by announcing plans to reinforce its military and diplomatic presence in the Arctic, part of a broader effort to assert its sovereignty in a region that accounts for 40 percent of Canadian territory and 75 percent of its coastline.

Canada needs to act now because “the Northwest Passage will become a main artery of trade,” Riviere said, referring to the Arctic connection between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

Plans to bolster Canada’s Arctic presence include deploying new patrol ships, destroyers, icebreakers and submarines capable of operating under the ice cap, in addition to more planes and drones to monitor and defend territory.

Photo: AFP

‘ASSERT SOVEREIGNTY’

At the Joint Task Force North’s headquarters in Yellowknife, the capital of Canada’s Northwest Territories, huge hangars house planes capable of landing on frozen lakes.

There is equipment designed to filter salt water from ice floes, and tents made for temperatures of -50 degrees Celsius.

Moving military resources around the area is complex work that is carried out by Twin Otters, a strategic transport aircraft that can operate in rugged environments.

On the tarmac after a flight over vast expanses of snow, forests and frozen lakes, Major Marlon Mongeon, who pilots one of the aircrafts, said that part of the military’s job is “to assert sovereignty of our borders and land.”

Canada has only a handful of northern military bases. To monitor the north, it relies on Canadian Rangers, reservists stationed in remote areas throughout the Arctic, many of whom are from the country’s Indigenous communities.

They’re known as “the eyes and ears of the north,” and some say their numbers need boosting in order to meet Canada’s evolving challenges. The Rangers monitor more than 4 million square kilometers, relying on their traditional knowledge of survival in this inhospitable area combined with modern military techniques.

They have been patrolling the country’s farthest regions since the Cold War began in the late 1940s, when military officials realized the Arctic was a vulnerable access point.

‘MOST HOSTILE THREAT’

“Having people from the area who know the land and the hazards, especially in the barren lands up there, to help assist you to get somewhere is vital,” said Canadian Ranger Les Paulson.

Because the military can’t deploy full-time soldiers across the entire region, the Rangers offer a rapid response option in remote communities, including in the event of “a breach of sovereignty” or airplane or shipping accidents, explained Paul Skrypnyk, 40, who is also a Ranger.

Climate change has made the Northwest Passage increasingly accessible to ships for navigation during summer months. That promises to shorten voyages from Europe to Asia by one to two weeks, compared to the Suez Canal route. Increased traffic, including among cruise ships, has compelled Canada to boost its capacities in the region to respond to accidents or emergencies.

In Yellowknife, training is being stepped up to prepare for a range of significant events, including how to respond to a fall into icy waters. Among those training was Canadian Ranger Thomas Clarke.

Still soaked from his jump into a hole dug in the sea ice, Clarke said that in the Arctic, the environment remains the greatest danger. “Mother nature... is the most hostile threat,” he said. “Mother nature will try to end you, before anything else.”

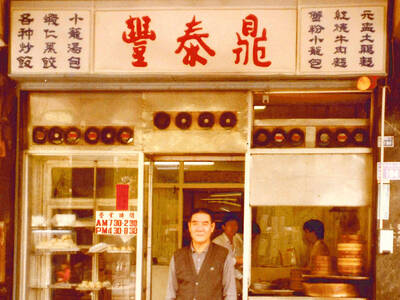

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

Indigenous Truku doctor Yuci (Bokeh Kosang), who resents his father for forcing him to learn their traditional way of life, clashes head to head in this film with his younger brother Siring (Umin Boya), who just wants to live off the land like his ancestors did. Hunter Brothers (獵人兄弟) opens with Yuci as the man of the hour as the village celebrates him getting into medical school, but then his father (Nolay Piho) wakes the brothers up in the middle of the night to go hunting. Siring is eager, but Yuci isn’t. Their mother (Ibix Buyang) begs her husband to let

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike