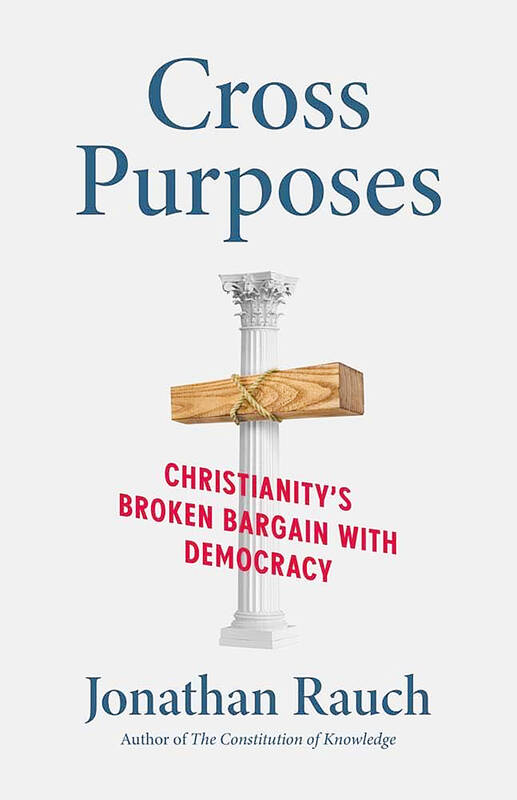

“What happens to our liberal democracy if American Christianity is no longer able, or no longer willing, to perform the functions on which our constitutional order depends?” Jonathan Rauch asks in the opening pages of Cross Purposes. “The alarming answer is that the crisis for Christianity has turned out to be a crisis for democracy.”

Rauch is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a contributor to the Atlantic Monthly. Author of more than a dozen books, he is gay, Jewish and an atheist. The questions he poses are personal, even existential. He places his own identity and experience at the fore.

“I feel an immense pride in America’s pluralism and tolerance while remaining conscious … of my status as a minority and an outsider,” Rauch explains. “I feel that my sense of belonging to America does not translate into a sense that America belongs to me.”

He loves the US but is now uncertain the country loves him back. The seemingly gentle mainline Protestantism that undergirded the US during the 1960s and 1970s gave way to something more jagged. Harsher and angrier, this Christianity is also less secure in its primacy of place, a cudgel fused to blood and soil.

“All nations before him are as nothing; and they are counted to him less than nothing, and vanity,” the prophet Isaiah once declared, seemingly forgotten by the Christian nationalists of today. Then again, scripture is read in myriad ways.

‘CHURCH OF FEAR’

Rauch labels the current iteration “Sharp Christianity, the Church of Fear.” It wields power, reaches into the Oval Office, yet sees itself besieged. It decries modernity and is very much of it.

Sharp Christianity proclaims the word of God and makes deities of flesh and blood, in Rauch’s telling. At the Capitol on Jan. 6, markers of Christianity and paganism stood adjacent to the gallows.

Franklin Graham, son of the late Billy Graham, threatens Americans with God’s wrath if they criticize Donald Trump.

“The Bible says it is appointed unto man once to die and then the judgment,” he posted to Facebook.

Another famous scion, the disgraced Jerry Falwell Jr, admonished his flock to stop electing “nice guys.” Instead, he tweeted: “The US needs streetfighters like Donald Trump at every level of government.”

In such words, resentment and grievance supplant the Bible and “What would Jesus do?”

Then again, amid the carnage of the actual civil war, all combatants looked to Christianity for justification and succor.

“Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other,” Lincoln observed, in his second Inaugural. “The prayers of both could not be answered — that of neither has been answered fully.”

The Battle Hymn of the Republic, by Julia Ward Howe, an abolitionist, sings of “His terrible swift sword,” leaving no room for ambivalence or ambiguity. “As he died to make men holy, let us die to make men free / While God is marching on.”

At the same time, below the Mason-Dixon line, churches and stained-glass windows paid homage to Robert E Lee and Stonewall Jackson. The cross, the flag and the slaver’s whip were beatifically stitched together.

Rauch also engages in personal soul-searching.

“I was smug about secularization,” he confesses. “I began bending an ear to warnings that Christianity’s crisis is democracy’s, too. I came to realize that in American civic life, Christianity is a load-bearing wall. When it buckles, all the institutions around it come under stress, and some of them buckle, too.”

By the numbers, religious “nones,” at 28 percent of the US population, exceed evangelical Protestants (24 percent) and non-evangelicals (16 percent). Attendance at worship drops. Twenty years ago, according to Gallup, 42 percent of US adults attended religious services every week or nearly every week. By the middle of the 2010s, it was 38 percent. Now, only three in 10 regularly fill the pews.

“Both of its major streams, the ecumenical and the evangelical, have ‘thinned,’ that is, secularized, albeit in very different ways,” Rauch writes. “Neither is as capable of providing meaning and moral grounding as it once was or today needs to be, and secular alternatives like science and SoulCycle cannot, even in principle, fill the void.”

He acknowledges that he did not fully comprehend America’s civic religion.

‘WALL OF SEPARATION’

“I did not appreciate the implicit bargain between American democracy and American Christianity,” he states. “I would have said that the basic deal was to leave each other alone — ‘wall of separation’ and all that. Their only bargain, I thought, was to make no bargain; to the greatest extent possible, religion and government should tend to their separate businesses and not interfere with each other.”

That take hasn’t aged well.

Protestantism was part of America’s big bang. Religious turmoil in England coincided with the first rounds of migration to the New World. The American revolution owed a particular debt of gratitude to Protestant dissenters. Colonial Congregationalists and Presbyterians came to owe little allegiance to the crown, less to Canterbury. Later, battles over slavery, prohibition, civil rights and the Vietnam war also played out within America’s churches. Those divisions have remained. Not all wounds heal.

Rauch points to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and its capacity for compromise as a possible model for other segments of Christianity to follow. But personal conservatism and social cohesion are born of Mormon homogeneity and conformity. Voluntary safety nets spring from self-identification with their beneficiaries. As Jonathan Haidt of New York University has repeatedly observed, diversity and cohesion seldom go hand in hand.

The US marks its 250th birthday on 4 July next year. From the vantage points of 21st-century America, looking back over two millennia provides no clear solution.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that