Jan 13 to Jan 19

Yang Jen-huang (楊仁煌) recalls being slapped by his father when he asked about their Sakizaya heritage, telling him to never mention it otherwise they’ll be killed.

“Only then did I start learning about the Karewan Incident,” he tells Mayaw Kilang in “The social culture and ethnic identification of the Sakizaya” (撒奇萊雅族的社會文化與民族認定).

Photo courtesy of Hualien District Agricultural Research and Extension Station

“Many of our elders are reluctant to call themselves Sakizaya, and are accustomed to living in Amis (Pangcah) society. Therefore, it’s up to the younger generation to push for official recognition, because there’s still a taboo with the older people.”

Although the Sakizaya became Taiwan’s 13th official indigenous group on Jan. 17, 2007, a survey showed that most of the population under 50 had grown up identifying as Amis and did not even know the term until the cultural movement picked up in the 2000s.

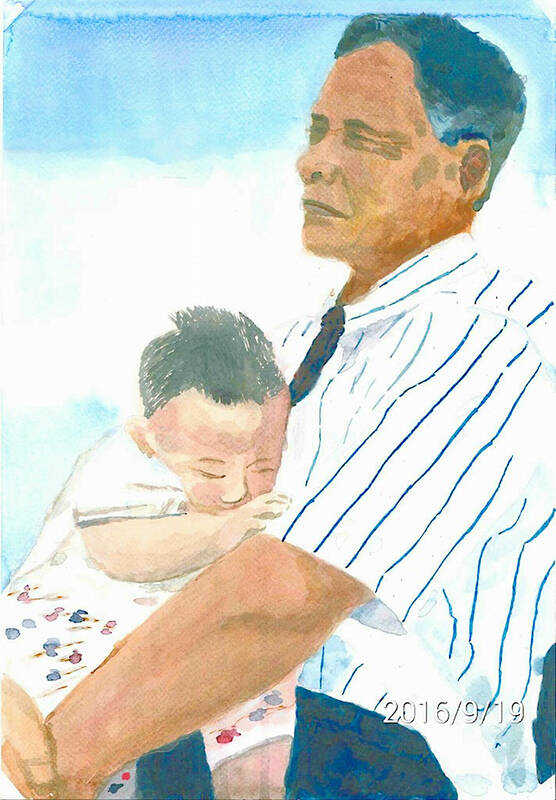

Mayaw was also clueless about his Sakizaya heritage until he met Tiway Saiyon, an educator and activist who, despite being a renowned expert in Amis culture, was also a relentless advocate for Sakizaya awareness.

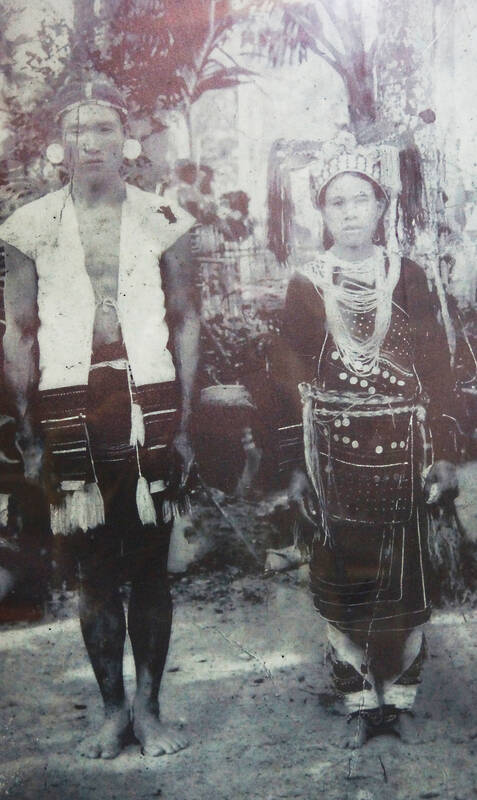

Photo courtesy of Kolas Yotaka

Tiway was raised by his grandmother, a survivor of the 1878 Karewan Incident in which the Kavalan and Sakizaya peoples rose up against Qing oppression. The two groups, once dominating the plains around today’s Hualien City, were decimated and forced to scatter and hide their identity, living among the Amis and adopting their customs. When the Japanese surveyed the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, they classified the Sakizaya as a branch of the Nanshi Amis, and the label stuck.

However, despite more than a century of close interaction and intermarriage, the differences between the two peoples persisted, especially the languages that were not mutually intelligible. Mayaw's Amis grandfather, for example, married into a Sakizaya family and learned the language, and his father was fluent in it as well.

The Sakizaya did not want their split from the Amis to be acrimonious; this is shown in their 2005 declaration: “We’ve been wandering for 127 years, it’s time to go home. The Sakizaya will forever remember with gratitude and respect the sun’s warmth, our mother’s love and our deepest friendship with the Pangcah.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

ORIGIN DISPUTE

Spanish records from 1632 note the existence of the “Saquiraya” living in the district of “Turoboan.” They added that the villages produced gold and silver, leading some modern experts to believe that Turoboan was located in the northeast coast around today’s Jiufen District (九份) in New Taipei.

Huang Hsuan-wei (黃宣衛) writes in “From the south, from the north – Inspecting the literature on the origins of the Sakizaya” (南來說北來說 關於薩奇萊雅源流的一些文獻考察) that this theory originated from Jose Borao’s 1993 paper “The Aborigines of Northern Taiwan according to 17th Century Spanish Sources” and was perpetuated in Hsu Mu-tsu’s (許木柱) 2003 book, Reconstruction of the history of Hualien City’s indigenous villages (花蓮市原住民部落歷史重建).

Photo courtesy of Hualien District Agricultural Research and Extension Station

However, the Liwu River (立霧溪) in Hualien County also produced gold, and Huang writes that it is more likely what Spanish sources referred to. In fact, Borao’s 2001 book The Spanish Experience in Taiwan places Turoboan squarely on the Hualien coast and “Saquiraya” just west of Hualien City, where the historic main settlement of Takobowan (today’s Sakul) was located.

Tiway, on the other hand, was adamant that the Sakizaya were originally Siraya from Tainan who were pushed out of their homeland by the arrival of Ming Dynasty warlord Koxinga, also known as Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功), in 1662.

He posited that “Siraya” was a Chinese corruption of Sakiraya (alternate pronunciation of Sakizaya) and that Takobowan was named after Taiovan in today’s Anping District (安平), Tainan. This contrasts with the Spanish observation that the Sakizaya had already been in Hualien County in the early 1600s.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Huang concludes that there is insufficient evidence to support both claims, plus Sakizaya origin myths also indicate that they have been in Hualien County since at least 1600 and have long associated with the Amis. Both theories emerged during the time when Sakizaya were seeking separate recognition from the Amis, hoping to show that they had disparate origins.

THE VILLAGE BURNS

The Sakizaya first encountered the Kavalan around 1840, when the latter were forced south due to Han Taiwanese settlers encroaching on their original home in Yilan County. The two sides briefly clashed when the Kavalan tried to expand south of the Meilun River (美崙溪); that marked their boundary and they became close allies against the Truku to the northwest. The Kavalan named their new settlement Karewan.

This new home came under threat once more with the Qing’s “open the mountains and pacify the savages” (開山撫番) policy in 1874, as the government began stationing troops on the east coast and encouraging Han settlers to move there. The Kavalan appeared receptive to this at first, hoping that pledging allegiance to the Qing would provide protection against Truku and Han incursions. However, things turned sour as the number of soldiers increased and began oppressing the populace.

In 1878, Kavalan representatives headed to the army camp to air their grievances, only to be slaughtered. This finally pushed them over the edge, and their Sakizaya allies also joined the fray.

As a child, Tiway’s grandmother would tell him about the events that transpired next, and he published one of the earliest modern accounts of the Karewan Incident in 1989.

After several clashes, Qing reinforcements arrived in September and decided to take down the Sakizaya first to isolate the Kavalan. At that time, Takobowan was surrounded by a thick defensive bamboo forest planted over centuries, making it hard to penetrate. However, rival groups informed the Qing where the entrances were, but due to the narrow path no soldier made it into the village alive.

As the bodies piled up by the gate, the Qing resorted to shooting fire arrows at the settlement, and as the place burned, the Sakizaya chiefs surrendered.

Takobowan chief Kumud Pazik and his wife Icep Kanasaw reportedly stayed behind so that the younger villagers could escape; the two were brutally executed in public. Today, they are worshipped as fire deities and are the focus of the Sakizaya’s annual “palamal” fire ceremony.

RECLAIMING IDENTITY

A 16-year-old Tiway Kalang and 13-year-old Rutuk Sayion fled south to Ciwidian Village in today’s Shoufeng Township (壽豐) in Hualien County and established a Sakizaya settlement; they became Taway Tiway's paternal grandparents, writes Sayum Bolaw in “The etho of Sakizaya — Ethnic identity and cultural practice” (撒奇萊雅族的精神—族群認同與文化 實踐).

Other survivors also established new settlements or took refuge in Amis villages, while some eventually returned to Takobowan and founded the new village of Sakul, although it was much smaller than before. Nevertheless, they vowed to keep their identity a secret in fear of retribution, blending in with the surrounding Amis and adopting their customs.

This taboo persisted until modern day; when Mayaw was doing field research for his thesis in the late 1990s, he had great trouble finding Sakizaya subjects outside of those he knew personally. Interestingly, he found that the most effective way was to ask the Amis which people in the villages were Sakizaya — and they almost always knew, showing that a tacit difference still existed.

Tiway is considered the first to bring attention to the issue, holding the first ancestral worship ceremony using the name Sakizaya in July 1990. However, most still preferred to identify as Amis, and nothing came of the effort. By 2001, however, he told Mayaw that he had decided to give his all to reviving Sakizaya culture. In 2003, a year after the Kavalan were officially recognized, he held a meeting with elders and leaders and vowed to seek official recognition.

Tiway died later that year, and after a brief lull, his son Tuku Tiway along with Sayum Bolaw launched a new task force and recruited other young people to continue the push. After three years, they finally succeeded.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she