Like many works of historical fiction, this is a slow burner. Unlike some, this is not down to painstaking characterization.

Aside from oneiric recollections of an unexplained childhood isolation at a mountain temple, to which she attributes her “monstrous” gluttony, the book’s narrator Aoyama Chizuko reveals little about herself.

She has achieved success with her debut novel, A Record of Youth, featuring a heroine who finds fame as a writer, despite early setbacks. After her mother dies during childbirth, partly — it is indicated — due to the baby’s size, the protagonist is sent to a “branch family,” where she is nurtured by a kind but mollycoddling aunt.

Adapted into a film, the tale appears autobiographical, though Aoyama denies this. “Movies are movies. Novels are novels. I am me,” she says.

A burgeoning reputation earns Aoyama an invitation from Taiwan’s Government-General and the Nisshinkai women’s organization of Taichu Prefecture (modern day Taichung) to visit Taiwan where she embarks on a lecture tour. She had long dreamed of visiting the island colony but had turned down a lucrative offer from a magazine that wanted a serialized novel championing Japan’s “Southern Expansion Policy.”

This refusal to promote Tokyo’s agenda demonstrates Aoyama’s seemingly noble intentions but leads to a chastening self-reflection. The sincerity of her attitude becomes a crucial element in her relationship with Taiwan, as personified by Ong Tshian-hoh, or Wang Chien-ho, a young Taiwanese interpreter.

After a chance meeting, Aoyama secures Ong’s services in place of the fusty civil servant Mishima, who fails to oblige the novelist’s repeated efforts to seek and scoff “Islander” food. Aoyama nicknames her new companion Chi-chan to avoid confusing their Japanese given names, which share kanji characters.

In addition to her language skills, keen intellect, and inexhaustible knowledge of Taiwanese cuisine, Chi-chan has a remarkably similar background to her Japanese companion, who is several years her senior. She becomes Aoyama’s guide and — though it remains unspoken — love interest.

Born to a geisha turned concubine to a wealthy landowner, Chi-chan was initially sidelined by her father and legitimate siblings and temporarily sent to farm jute with her mother’s peasant relatives. This haunts her, when she encounters her half-sisters at a tearoom, with the latter feigning astonishment that one who grew up eating mua-inn-thnng (jute soup ) is frequenting such establishments.

There is a hint of the Gothic doppelganger in the parallel backgrounds of the two women, yet more than character insights, it is the delayed decoding of Chi-chan’s past and the gradual slipping of her “Noh mask” that intrigues. While the denouement is unsurprising, the themes evoked by the unraveling of Chi-chan’s secret, and the devices employed, are engaging.

OPPOSITES ATTRACT

The standout episode here comes during a trip to Tainan where Aoyama is to deliver a lecture at a high school. When a pair of students are assigned to show the visitors around, the duality surrounding Aoyama and Ong is thrown into relief.

Like Aoyama, whose height earned her the sobriquet “Great Cedar” as a girl, and Ong, who is petite with child-like dimples, the classmates are physical opposites — the Taiwanese Tan Thsiok-bi is “as delicate and spindly as a prepubescent boy,” while her Japanese classmate Ozawa is “broad shouldered and full bosomed.” Ozawa, a wansei (Taiwan-born Japanese) plays “protector” to her friend, and the visitors notice subtle interactions, such as Ozawa’s brushing of petals from Tan’s shoulders.

Images of blossoms — “cascading,” “waterfalling,” and blown “into flurries in the sky,” before nestling on shoulders and in hair — recur. Bougainvillea, trumpetlower, and chinaberry fill Aoyama’s reflections and dreams. Lost in revelry, Aoyama becomes the romantic lead in a shojo novel, a style of fiction targeted at girls in which floral motifs abound. Softness then turns to sharpness, the imagery attaining a violence that requires greater resolution.

“[H]ad arrows showered down instead of flowers,” muses Aoyama, “I would have shielded Chi-chan’s body with my own.”

EXOTICIZING THE ISLAND

Yet, the guardian-ward dynamic is more complex: Tan asserts agency through “small acts of rebellion,” even repurposing an ethnic slur against Taiwanese and transforming it into a term of endearment for Ozawa. A photo gifted to Ozawa by Tan of the latter in riding gear, astride a horse, which Chi-chan surmises is intended to show strength and reliability, emphasizes the shifting roles.

Parallels with the the protagonists are obvious: Explaining her rejection of Aoyama’s attempts at intimacy, Chi-chan recalls Tan’s “resistance,” speculating that it rebuffed Ozawa’s “misguided treatment.” For, despite kind intentions, neither Ozawa or Aoyama asks “the docile Islander” who they “treasure and care for” whether they want this protection, Chi-chan observes.

This idea is revisited in the penultimate chapter, and the use of Mishima to hammer it home is a masterly touch. Having assumed that he is a phlegmatic minion, Aoyama, and indeed the reader, discover that this "unyielding Government General bureaucrat" is also affronted by the tourist’s heady exoticization of the “Southern Island.”

As a wansei, Mishima is deeply attached to his homeland and, despite fulfilling his duties as an imperial administrator, does not share Aoyama’s enthusiasm for the “wonderful things” the Empire has done for its colonial subjects.

Given free rein to vent, he accuses Aoyama of “intellectual arrogance” in using “arbitrary and subjective criteria” to assess the purported benefits of the Southern Expansion Policy.

MUTUAL DEBASEMENT

“Whether you choose to criticize or support these policies had little to do with whether the Empire has caused harm or done good,” says Mishima.

“It has more to do with your personal preferences.”

With his insider’s view of the colonial project — the quotidian brutality of which the giddy visitor is blissfully ignorant — Mishima understands what Orwell identified as the imperialist’s shame and concomitant debasement of both colonizer and colonized. Like the role reversals and dualities that emerge in the book, Mishima’s positionality as a neither-nor figure points to deconstructions of prevailing attitudes toward the colonizer-colonized dichotomy by thinkers such as Aime Cesaire and Frantz Fanon.

It would be remiss not to mention the two most obvious elements of this novel: its structure and thematic organization around Taiwanese food.

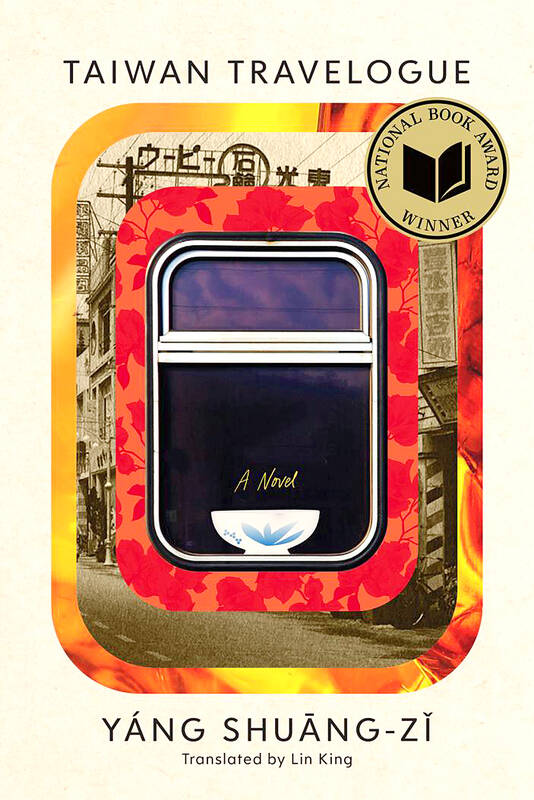

As noted in an afterword by translator Lin King (金翎), upon release, the original Chinese-language novel in 2020 left some readers feeling duped, as the fictional Aoyama was listed on the cover as the author, while Yang Shuang-zi (楊双子) was cited as the translator.

Many readers in Taiwan bought the claim Taiwan Travelogue was a rediscovered novel by an obscure Japanese writer.

This is unsurprising: detailed knowledge of the colonial era is still lacking in Taiwan, partly due to decades of Chinese Nationalist Party efforts to expunge the period from the historical record.

ORGASMIC GLUTTONY

As for the culinary theme, each chapter is dedicated to a specific dish that elucidates aspects of Taiwanese society.

A notable example is Kiam-Nng-Ko / Savory Cake, the chapter featuring Mishima’s broadside.

Popularized by a visiting Japanese prince, this speciality of Toyohara, present-day Fengyuan District (豐原區), comprises a “western” sponge cake exterior with a braised pork filling, adeptly representing Taiwan’s position.

Elsewhere, the sustained gorging symbolizes pent up sexual frustrations, edging toward climax in the Tsai-Bue-Thng (Leftovers Soup) feast, which recalls the deadly excesses of Marco Ferreri’s cult satire La Grande Bouffe.

Most of all, Taiwanese pride in authentic local cuisine is captured in these descriptions. For, despite her hammed up praise of almost everything she devours, Aoyama seems sincere in her appreciation of that most beloved Taiwanese accompaniment to rice — braised pork, lurou (滷肉), which like other items, is referred to using Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese).

“Anyone who can discriminate against loo-bah,” Aoyama declares, “must be completely incapable of appreciating good food.”

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the