In 1990, Amy Chen (陳怡美) was beginning third grade in Calhoun County, Texas, as the youngest of six and the only one in her family of Taiwanese immigrants to be born in the US.

She recalls, “my father gave me a stack of typed manuscript pages and a pen and asked me to find typos, missing punctuation, and extra spaces.”

The manuscript was for an English-learning book to be sold in Taiwan.

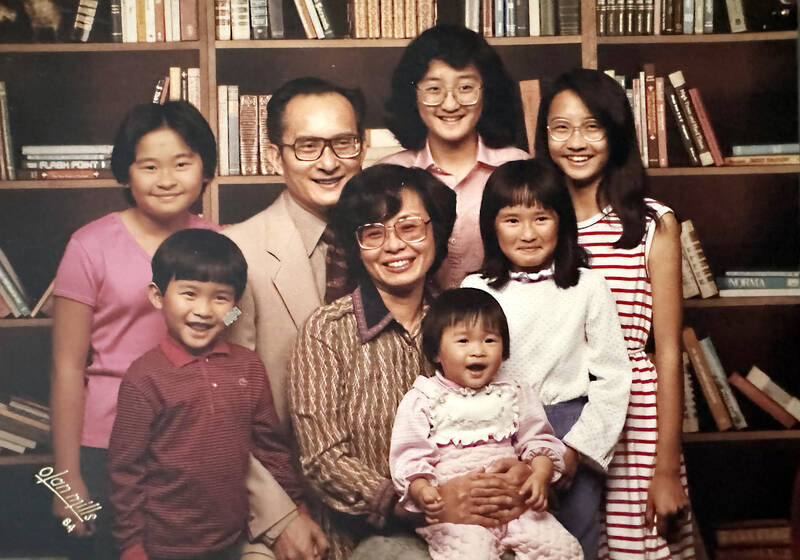

Photo courtesy of Amy Chen

“I was copy editing as a child,” she says.

Now a 42-year-old freelance writer in Santa Barbara, California, Amy Chen has only recently realized that her father, Chen Po-jung (陳伯榕), who died in 2014, made a fortune in 1970s Taiwan as an impresario of English-language education.

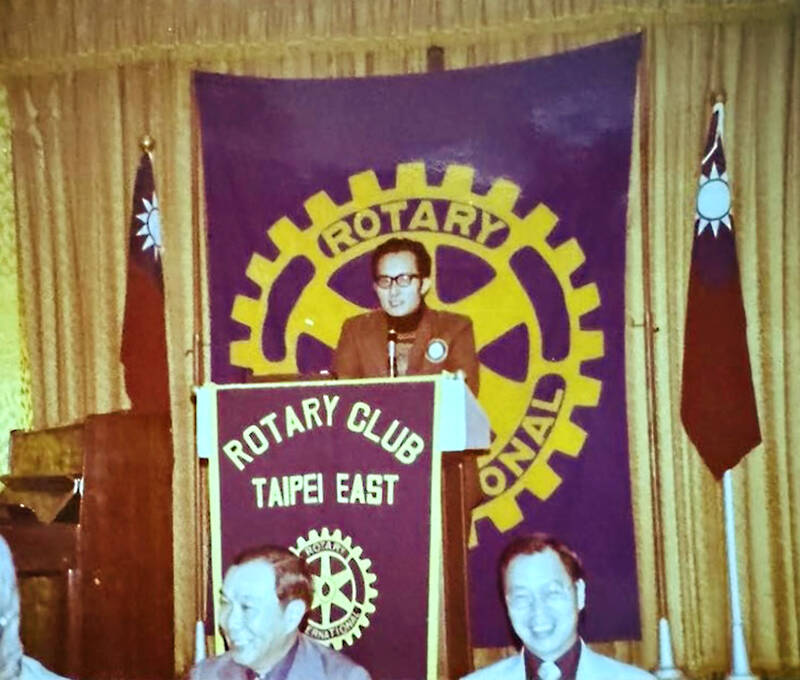

Teaching to auditoriums of students, hosting radio shows, running a private language center and founding a publishing house for language learning books, Chen Po-jung stood at the forefront of a language learning wave that allowed Taiwan to internationalize and do business with the world.

Photo courtesy of Amy Chen

Amy Chen, through recent conversations with her 79-year-old mother, Susie Chen (陳素子), has discovered a completely new image of her father.

“I grew up with bankruptcies and foreclosures ... money was very tight,” she says.

But in Taiwan, Chen Po-jung owned prime Taipei real estate from teaching English to clients from Taiwan’s military and major financial institutions to hundreds of thousands of ordinary citizens.

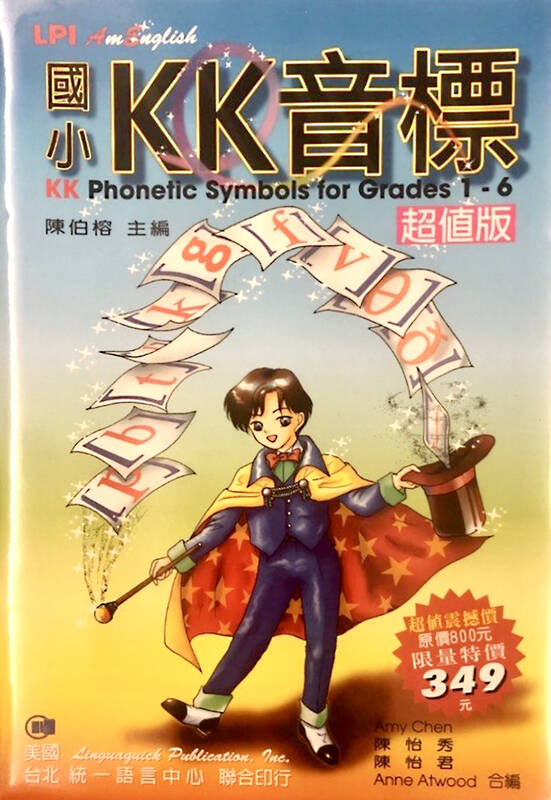

Photo courtesy of David Frazier

“My mom told me that when flying into Taiwan, officials at the immigration checkpoint would often recognize my dad, and say things like, ‘Teacher Chen, I learned English using your books!’ They’d be extremely respectful and quickly wave them through,” she says.

Amy Chen says she’s embarrassed that she’s only recently become aware of this family history.

“So much of my life was about assimilating [to life in the US]” she says, ruefully admitting she’s only been to Taiwan twice and speaks very little Mandarin.

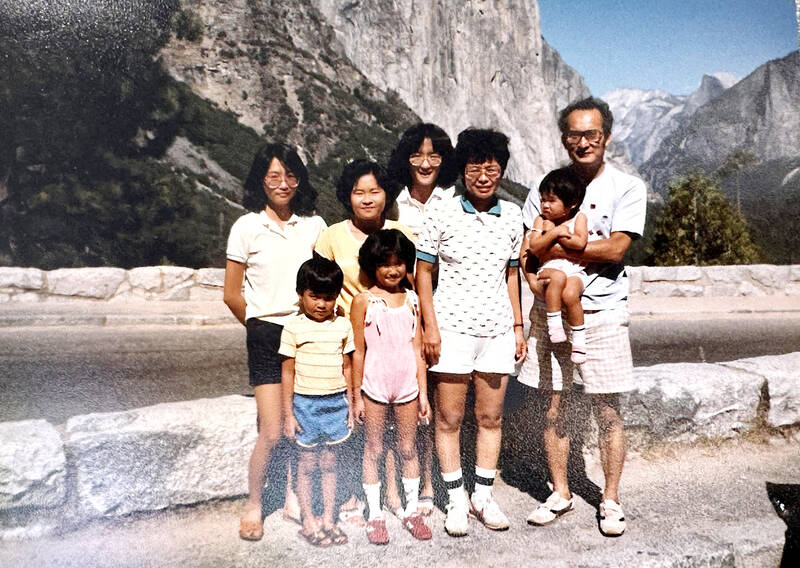

Photo courtesy of amy chen

It wasn’t until recent conversations with her mother that she realized, “there was a whole rich life in Taiwan before they immigrated. And that window of being able to ask that generation really is rapidly closing.”

To try to piece together her family’s story, Amy Chen, a journalist, has produced an 80,000-word manuscript draft of a family memoir.

For her, the enormous gap that remains in this family history is her father’s life in Taiwan and his impact there as one of Taiwan’s first-generation English as a second language (ESL) entrepreneurs.

Amy Chen recently put out an open call on LinkedIn, asking if anyone could help her answer questions, like: “How did my father’s language books change the trajectory of someone’s life? How did learning English open any doors?”

Her post struck a chord with networks of second-generation Taiwanese-Americans and Asian-Americans.

An engineer from Meta had seen her father’s dictionary in a Taiwanese community center in Houston, Texas. A Malaysian-Chinese woman said she’d bought that same dictionary, purchased in Malaysia in the early 1990s, provided her with a linguistic crutch during her graduate studies in Pennsylvania.

TAIWAN’S ESL EXPLORATION

Amy Chen has so far discovered that her father was born in 1936 in a small coastal farming community outside Taichung during the Japanese occupation, aged just nine at the end of World War II, when Japan relinquished Taiwan to Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣中正) Chinese Nationalists and the language taught in schools switched from Japanese to Mandarin.

According to research by Scott Sommers, an assistant professor at Taipei’s Ming Chuan University who studies language policy in East Asia, since its inception in 1912, the Republic of China (ROC) government had elevated English to become “the second language of China’s Republican elite class” as “the vast majority of technical and scientific information was still available only in English.”

In the chaos of the late 1940s, when Chiang retreated to Taiwan with between one and two million mainland Chinese, his government was unable to implement widespread English education. Still, in 1954 the ROC reinstated the Joint College Entrance Exam, or liankao (聯考), the single gateway to Taiwan’s universities, which required English testing of all applicants.

For native-born Taiwanese, discriminated against by the newly-arrived mainlanders and with little access to English lessons, the exam was especially daunting.

But Chen Po-jung was exceptionally bright. As a teen he earned a scholarship to boarding school and became the first member of his family to attend junior high school. He then tested into the nation’s top learning institution, Taiwan National University (NTU), where he received a degree from the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures.

Upon graduation, he worked in Taipei as a translator for the US Air Force who operated several bases in Taiwan through the 1960s, swelling during the Vietnam War.

Chen Po-jung also taught in private language centers, earning a reputation as an expert in English grammar. He presented lessons on Taiwan’s national public radio station, the Broadcasting Corporation of China (BCC), and conducted in-house English training for the nation’s major financial institutions, including the Cathay Financial Holdings Group.

Newspaper advertisements from the late 1960s show that Chen Po-jung toured to major cities in central Taiwan including Taichung and Tainan to lecture on English test prep.

During that era, Taiwan’s English-language education focused “mainly on test prep and knowledge of English grammar, rather than communicative competence,” said Sommers.

Taiwan’s schools were a China-transplanted education system that relied on rote memorization and based advancement on test scores. The Examination Yuan to this day is still devoted to an extensive system of national examinations.

In 1968, Taiwan’s government, eying international competitiveness, made at least three years of English classes compulsory for all junior high school students.

The shift led to an early boom in private language centers, as thousands of young Taiwanese beyond the junior-high level were desperate to catch up.

“They saw English as the future, and there was a voracious desire to learn it,” says Amy Chen.

GOLDEN ERA

As a master grammarian, Chen Po-jung’s star rose quickly.

He refocused his target audience to junior high education and moved to Taipei. In the early 1970s, he set up the Tongyi Language Center, a private cram school, and the Tongyi Culture Publishing Company in the capital’s epicenter of cram schools and bookstores, the crowded streets around Taipei Main Station.

One of Chen Po-jung’s early innovations was the pairing of textbooks with vinyl records and later cassette tapes, CDs and MP3s.

Over the next two decades, Taiwan’s English-language education exploded alongside the “Taiwan economic miracle,” as the nation’s per capita income rose twenty-fold, from under NT$400 in 1970 to over NT$8,000 by 1990, according to Taiwan’s National Development Council.

In 1995, one scholar estimated that more than 450,000 Taiwanese from a total population of 21 million were enrolled in private English classes.

“My parents made millions,” says Amy Chen.

In Taiwan, they purchased expensive properties, including the bookstore near Taipei Main Station, three parcels of land in Hsinchu County and a four-bedroom apartment on Taipei’s exclusive Renai Road.

Amy Chen has so far located dozens of Tongyi titles with publication dates from the 1970s up to 2014. Books like Elementary Practical AmEnglish — a contraction of “American English” invented by her father — featured images of American icons like the Statue of Liberty, Superman or Mount Rushmore on their covers.

Some of these books still sit on the shelves of Taiwanese libraries and bookstores, and a few list the author as Amy Chen or her sister, who used the English name Anne Atwood, “because [my father] thought it would sell better with English names as co-authors,” she explains.

Over the years, Chen Po-jung’s traditionalist, grammar-heavy approach to ESL fell from favor. In 2001, as part of wide-ranging education reforms, English-language education began to emphasize communication skills over rote memorization. Public school students now study at least ten years of English, beginning from third grade, though many begin even earlier in private English kindergartens.

Today, Tongyi Publishing is run by Chen Po-jung’s 52-year-old nephew Chen Hung-chang (陳宏彰) and has at least 180 language-learning titles for sale, including 32 by Chen Po-jung, according to Taiwanese bookseller websites. Chen Hung-chang however says Chen Po-jung’s books are all old stock and will not be reprinted. The press’s newer books focus on teaching Chinese to Taiwan’s growing populations of Vietnamese, Indonesian and Thai immigrants.

THE AMERICAN DREAM

Though Chen Po-jung struck gold selling English in 1970s Taiwan, in 1980 he decided to bring his family to America, a dream for many Taiwanese in that era who could not foresee the end of Taiwan’s martial law in 1987 nor the advent of a full democracy in 1996.

Chen Po-jung had enrolled in a Masters of Education at Harvard University at the age of 44, still flush with publishing profits and running the business with the help of his brothers in Taiwan. The following January, his wife and five children joined him.

“My mom remembers they landed in a snowstorm,” says Amy Chen.

Her mother quickly tired of the New England snow, so once her father earned his degree, they moved to Southern California to join Taiwanese friends in the summer of 1981, she said.

A year later, Amy Chen was born in Orange County’s Mission Viejo.

But growing up, “my parents had to keep selling things off in Taiwan to fund my father’s American Dream as a real-estate developer,” she said.

As for the father she remembers, “he always had a kind of corny sense of humor,” she recalls, noting that he would buy joke books and integrate the jokes into the teaching materials.

“I remember we would get into arguments about idioms. Because he’d use these expressions in his books, and I’d tell him, ‘No one says that.’”

“Now I’m thinking, ‘Gosh, I hope there’s not a whole generation of people who are using his colloquialisms and idioms that actually aren’t a thing.”

Though Amy Chen has been able to sketch her father’s story, the fogs of time and cultural distance still separate her from Taiwan and the impact of her father’s ESL work there.

She fantasizes that her father’s books might’ve taught English to “Nvidia’s Jensen Huang, or someone who’s achieved amazing things.”

“That to me would be the legacy of a life well lived,” she said, “especially knowing that the other half of his career didn’t pan out the way he probably wanted it to.”

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has