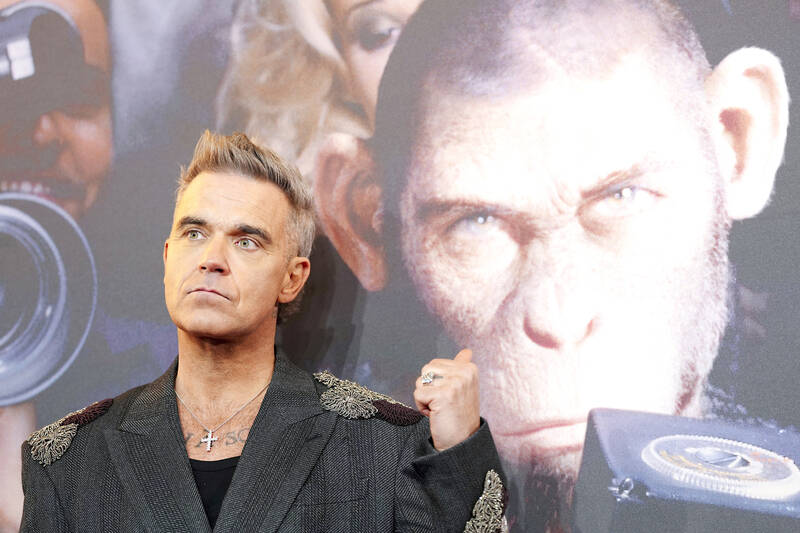

It was a throwaway comment: Robbie Williams, Take That’s cheeky chappie-turned-tabloid fodder solo phenomenon, described himself as a performing monkey, prancing and preening in front of the cameras and seeking the approval of the audience (or at least a banana or two).

But for director Michael Gracey (The Greatest Showman), it was the key to unlocking Williams’s conflicted relationship with his celebrity and his compulsion to perform. In a creative gamble to rival Piece by Piece director Morgan Neville’s decision to tell the Pharell Williams story with Lego animation recently, Gracey replaces Williams in this warts-and-all biopic with a CGI chimpanzee in an otherwise human cast.

It’s a gamble that not only pays off — it’s arguably the main reason the film works as well as it does.

Photo: AP

Narrated by Williams (Jonno Davies delivers a motion-captured performance as Robbie the Monkey) in a tone that strikes a precarious balance between wry self-deprecation and maudlin self-pity, the story itself is pretty generic stuff: a by-the-numbers trawl through the early hardship of Williams’s working-class childhood in Stoke-on-Trent, father-son tensions and industrial-level substance-abuse issues.

The film’s emotional beats — Williams’s doomed relationship with All Saints singer Nicole Appleton; the death of Robbie’s beloved nan — are hammered home with piledriver subtlety.

But the capering ape device transforms what would otherwise be a rote addition to the rock biopic canon, infusing the story with humor, mischief and a sparky, unpredictable anarchy.

Yes, Williams clearly takes himself pretty seriously and has a weakness for therapy-speak platitudes. But he also invites us to see him as a surly adolescent chimp in a shell suit. You have to love him for that.

Better Man is a notable step up for Gracey. The synthetic, rather soulless panache of The Greatest Showman demonstrated his skills as a slick visual stylist, but here he directs from the heart, tapping into the rawness and vulnerability beneath the CGI monkey suit.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,