In 1994 the writer Julian Evans went on a 10-day cruise down the Dnipro River. Ukraine had won its independence three years before. The journey took Evans along an ancient route used by the “restless Vikings” who established Kyiv. His ship — the Viktor Glushkov — stopped off at Crimea and Yalta. Its final destination was the glittering Black Sea port of Odessa.

Evans was a veteran traveler. Nonetheless, the city was “unlike any place I had visited,” he writes — a “country beyond the back of a wardrobe” where anything could happen. It had merchants’ houses, acacia trees, a dandyish 19th-century opera and ballet theater, and wide neoclassical boulevards. It was ostentatious and self-made. There was kolorit: exoticism and flash.

After seven decades of communist decay, mafia goons roamed the streets. In its gangster heyday, Evans recalls, Odessa was a “dusty Sleeping Beauty being kissed awake by a guy in a blacked-out Mercedes with a handgun in the glove box.” Regional crooks dominated. The city was full of stories, and known for sarcasm and wit. It was home to Isaac Babel, the poet Anna Akhmatova and Bob Dylan’s Jewish grandparents.

For Evans, it was the beginning of a three-decade love affair with Odessa and its people. He returned five years later to make a radio program about Alexander Pushkin, another resident, and got chatting to a waitress called Natasha. He invited her for a drink. A courtship followed — with walks, Moldovan wine and letters from London. Evans converted to Orthodoxy and married Natasha in a monastery.

Later they spent languid summers in Odessa with their two children. Meanwhile, Ukraine was changing from a Moscow-style bandit state to a fledgling democracy and what Evans calls an “emerging unlikely paragon of freedom.” Ukrainians were willing to fight for their rights, in contrast to their supine neighbors. There were street revolts in 2004 and 2014: against election cheating and a corrupt Kremlin-backed government.

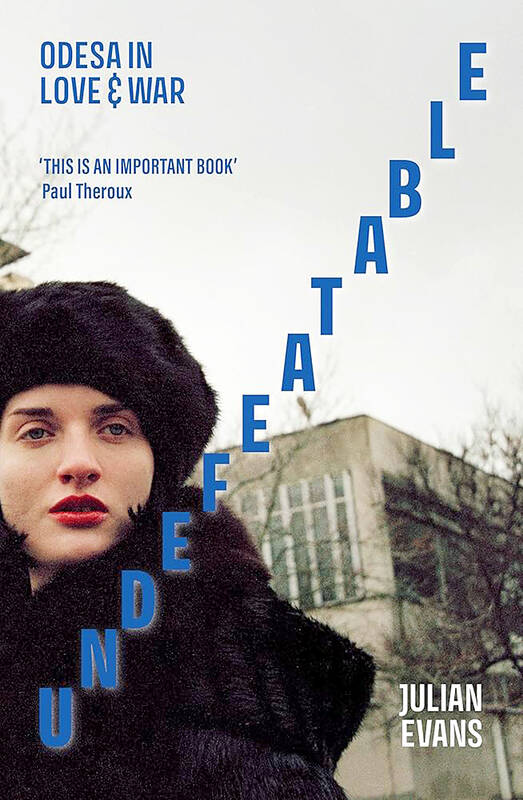

Evans’s new book is a brilliant portrait of a country and a city now under Russian attack. Most nights Iranian drones and Iskander ballistic missiles wallop Odessa, bringing murder and mayhem. The blossom-scented harbor promenade and Potemkin steps that enchanted Evans echo to Ukrainian anti-aircraft fire. Having failed to seize Odessa in the early weeks of his invasion, Vladimir Putin is busy destroying it.

The author’s relationship with the city lasted longer than his marriage, which eventually fizzled out. In 2015 he toured the then eastern frontline near Mariupol, following Russia’s covert part-takeover of the industrial Donbas region. In November 2022, he arrived in a missile-struck Odessa during a blackout. His mission this time was humanitarian: to donate a Nissan pickup to the outgunned Ukrainian army, plus tourniquets.

Evans is a wonderful writer and observer, a stylist as elegant and gloriously free-wheeling as the late Jonathan Raban. Each paragraph has a lapidary charm. There is plenty of history too, effortlessly told. Before the Vikings, Odessa attracted Greek colonists. Other settlers include Italian merchants and Tatars. It was always a place of migrants, and more than the southern imperial riviera capital of Catherine the Great.

The memoir offers a shrewd analysis of Ukraine’s present struggle and what it means. The British media has frequently got it wrong, Evans suggests. In 2014 it depicted Moscow’s attempted takeover as a fight between “Ukrainian nationalists” and “pro-Russian separatists.” The actual fault line was economic: between the country’s poor and super-rich. Ukraine’s oligarchs lit the “garbage fire” that made Russia’s war possible, Evans argues.

The nation’s fate now hangs in the balance. On the battlefield Russia is advancing. Internationally, there is a strong whiff of betrayal in the air, as Trump returns to the White House and Ukraine’s allies get tired. Trump has promised to resolve the war — borne from centuries of Russian oppression — in “24 hours.” It seems likely he will bully Volodymyr Zelenskyy into a “peace deal” on Moscow’s brutal terms.

Evans characterizes the invasion as fascist. The Kremlin’s goals of expansion and assimilation by force are identical to those of the Nazis in the 1930s, “if less efficiently executed,” he writes. It is “plain sordid imperial theft” and “robbery with violence.” If Putin prevails in Ukraine, he will gobble up other European nations. China and North Korea — which has sent troops to bolster Russia’s army — may launch grabs of their own.

After three years of all-out war, Ukrainians are exhausted. The west talks about moral principles, one disillusioned soldier tells Evans, but sends too few weapons to make a difference.

“Ukraine’s spirit is flagging from loneliness,” he says.

If Europe and America believe in freedom and democracy “we should not shy away from putting our soldiers on the ground.” There is little prospect of that happening.

During a visit in May, Evans finds young women sitting in ones or twos in a beachside restaurant in Odessa, enjoying the evening breeze. The Black Sea is cleaner than before. Dolphins appear. Missing from this dreamy scene are men. Some are at home, hiding from conscription. Others are fighting in trenches on the eastern front. Thousands lie in cemeteries under yellow and blue flags.

Taiwanese chip-making giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) plans to invest a whopping US$100 billion in the US, after US President Donald Trump threatened to slap tariffs on overseas-made chips. TSMC is the world’s biggest maker of the critical technology that has become the lifeblood of the global economy. This week’s announcement takes the total amount TSMC has pledged to invest in the US to US$165 billion, which the company says is the “largest single foreign direct investment in US history.” It follows Trump’s accusations that Taiwan stole the US chip industry and his threats to impose tariffs of up to 100 percent

On a hillside overlooking Taichung are the remains of a village that never was. Half-formed houses abandoned by investors are slowly succumbing to the elements. Empty, save for the occasional explorer. Taiwan is full of these places. Factories, malls, hospitals, amusement parks, breweries, housing — all facing an unplanned but inevitable obsolescence. Urbex, short for urban exploration, is the practice of exploring and often photographing abandoned and derelict buildings. Many urban explorers choose not to disclose the locations of the sites, as a way of preserving the structures and preventing vandalism or looting. For artist and professor at NTNU and Taipei

March 10 to March 16 Although it failed to become popular, March of the Black Cats (烏貓進行曲) was the first Taiwanese record to have “pop song” printed on the label. Released in March 1929 under Eagle Records, a subsidiary of the Japanese-owned Columbia Records, the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) lyrics followed the traditional seven characters per verse of Taiwanese opera, but the instrumentation was Western, performed by Eagle’s in-house orchestra. The singer was entertainer Chiu-chan (秋蟾). In fact, a cover of a Xiamen folk song by Chiu-chan released around the same time, Plum Widow Missing Her Husband (雪梅思君), enjoyed more

From insomniacs to party-goers, doting couples, tired paramedics and Johannesburg’s golden youth, The Pantry, a petrol station doubling as a gourmet deli, has become unmissable on the nightlife scene of South Africa’s biggest city. Open 24 hours a day, the establishment which opened three years ago is a haven for revelers looking for a midnight snack to sober up after the bars and nightclubs close at 2am or 5am. “Believe me, we see it all here,” sighs a cashier. Before the curtains open on Johannesburg’s infamous party scene, the evening gets off to a gentle start. On a Friday at around 6pm,