Nov. 25 to Dec. 1

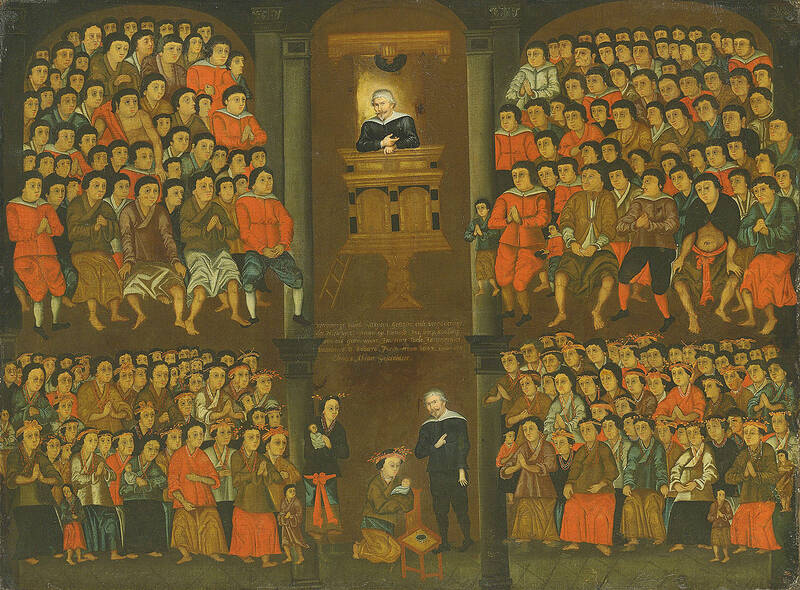

The Dutch had a choice: join the indigenous Siraya of Sinkan Village (in today’s Tainan) on a headhunting mission or risk losing them as believers.

Missionaries George Candidus and Robert Junius relayed their request to the Dutch governor, emphasizing that if they aided the Sinkan, the news would spread and more local inhabitants would be willing to embrace Christianity.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Led by Nicolaes Couckebacker, chief factor of the trading post in Formosa, the party set out in December 1630 south toward the Makatao village of Tampsui (by today’s Gaoping River in Pingtung County), whose warriors had taken the heads of several Sinkan residents in an earlier dispute.

Tampsui sent over 200 warriors to defend against the invaders, who scattered once they heard the sound of the Dutch rifles. The Sinkan gave chase and in the ensuing clash managed to claim one head and kill three to four more enemies. The Makatao then fled, ending the skirmish.

“The results of this expedition are satisfactory, for the minds of the people of Sinkan have been so favorably turned to us that the whole village shows an inclination to adopt our religion,” wrote governor Hans Putmans to Dutch East India Company (VOC) governor-general Jacques Specx in February 1631. “Some of the principal men … have cast away their idols and are being daily instructed by Candidus there being thus every appearance that progress of Christianity would be very great.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

At that point, out of the four main Siraya villages — Mattau, Soulang, Bakloan and Sinkan — near VOC headquarters in Tayouan (present day Anping District, Tainan), only Sinkan maintained relations with the Dutch despite earlier disputes (see Taiwan in Time: When a Siraya village requested the shogun’s protection, Nov. 17, 2024). That would change in a few years when the Dutch embarked on a year-long military expedition to subjugate the villages along the Tainan-Pingtung coast, with the Sinkan their staunchest ally.

POWER STRUGGLE CONTINUES

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The killing of 63 VOC soldiers in 1629 by Sinkan’s bitter enemy, the Mattau community, remained a sore point in indigenous-Dutch relations over the ensuing six years. Seeing that the Dutch did not have the numbers to exact revenge, the Mattau began openly taunting them, displaying in their villages the remains and belongings of the Dutch soldiers and ignoring any VOC attempts to summon them to Tayouan.

“We were regarded with very much contempt by all the people, especially by those of Mattau, who often showed how very little they were afraid of us, venturing not only to ill-treat the Chinese provided by our licenses, but even tearing up Your Excellency’s passports and treating them with contempt,” Junius writes.

But the Dutch were busy dealing with pirates and opening up trade with China and Japan, and the VOC refused to send reinforcements as they did not think Taiwan was worth investing in. However, their attack on the Mattau’s ally of Bakloan in 1629 and the expedition to Tampsui did curb the Mattau from further aggression.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile, the tangled power struggle between the four villages continued. In February 1632, the Sinkan made plans to raid the Bakloan. This alarmed the Dutch, who assumed that they would have to come to their aid. They met with the village council and made them acknowledge that the VOC “was like a father to Sinkan and if it were to leave, the village would be helpless against its enemies.”

Meanwhile the community’s tilt towards Christianity continued in earnest. In December, the village council signed an agreement with the VOC that they would no longer accept heathens and the priestesses would no longer perform their rituals. By 1633, Putmans reported that the community has “cast away their idols, and they all now call upon one and the same almighty true God.”

DESTROYING MATTAU

The following year, Candidus and Junius began pressing the VOC to allow one of them to travel with several Sinkan youths to the Netherlands so that they could train as clergymen. They believed that Sinkan was the most promising place in their domain to foster Christianity due to its lowest standing among the four villages: “The inhabitants expressed a longing to have someone to teach them, and thus be delivered from the people of Soulang and Mattau, who frequently molest them,” Putmans writes.

Meanwhile, local alliances continued to shift. The Soulang went to war with the Mattau, prompting the Sinkan to join forces with the Soulang. Tonio Andrade writes in How Taiwan Became Chinese that while the Mattau could prevail against the two villages, it was afraid that Sinkan’s involvement meant that the Dutch would join. Eventually, it sued for peace.

To maintain their alliance with the Sinkan, the Dutch assisted them on another headhunting expedition to the southern village of Takareiang. The Sinkan had earlier lost several men when it raided Takareiang with the Soulang; this time the Dutch shot five enemies, allowing the Sinkan to claim their heads.

The Dutch had been waiting for six years for reinforcements to arrive from the VOC capital of Batavia so they could finally exact revenge on the Mattau. They arrived in August 1635. A month later, the Sinkan unexpectedly revolted against the Dutch, but Junius heard of the plans and alerted Putmans, who sent troops to quash the incident before it could start.

A month later, VOC troops led by Junius and Sinkan warriors marched towards Mattau, which had been struck by a devastating smallpox epidemic. They burned down the village and killed 26 inhabitants, forcing them to sign a formal treaty. For a detailed account of the battle and the subjugation process, read “Taiwan in Time: Bringing down Mattau, Nov. 20, 2022.”

‘FULL OF ZEAL’

The Dutch were not done yet; they marched toward Takareiang, whose warriors had attacked Sinkan earlier and killed VOC employees, perhaps in retaliation for the headhunting expedition. They signed a similar treaty in February 1636.

They then entered Soulang and arrested eight villagers who had allegedly killed Dutch officers and missionaries several years earlier; the Sinkan were given the honor of executing them. In addition, Sinkan enjoyed an especially bountiful harvest that year.

“Many old persons in Sinkan, especially among the former priestesses, ventured to prophesy to the people at the time of their conversion, that, if they neglected their idols and began serving the God of the Dutchmen, their fields would no longer yield them their crops of rice,” Junius wrote in September 1636. “The people now laugh at their priestesses, whose words were formerly believed as oracles, and were believed with the same certainty and conviction which we have as regards to the Gospel.”

A school had opened for the youth of Sinkan, teaching them to read and write in addition to religious doctrine. About 500 to 600 people gathered for mass every Sunday, and Junius reported 50 weddings conducted by the priests in Christian fashion.

“The young natives are full of zeal,” Junius wrote. “Yes, there are many among them who can pray ... so well, and in so orthodox a way, that it is a pleasure to hear them.”

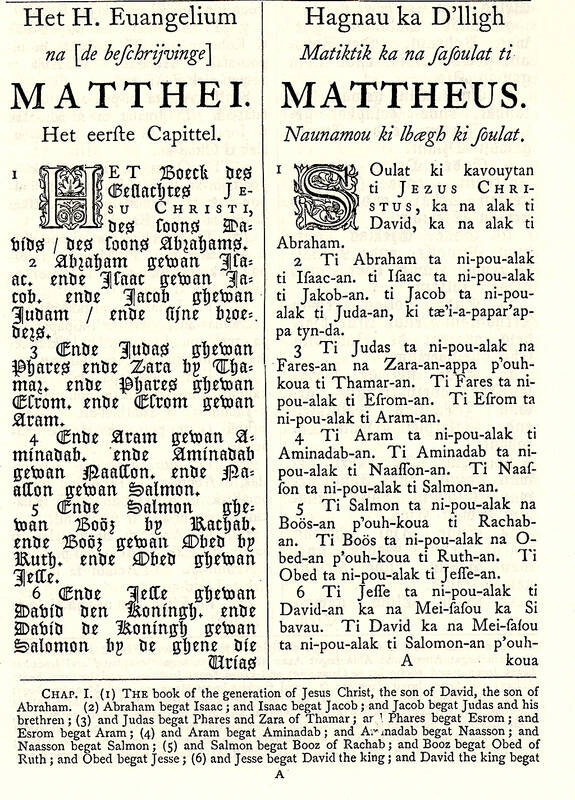

By the time Junius left Taiwan in 1643, records show that he had baptized more than 5,400 people in six villages — including the previously hostile Mattau and Soulang.

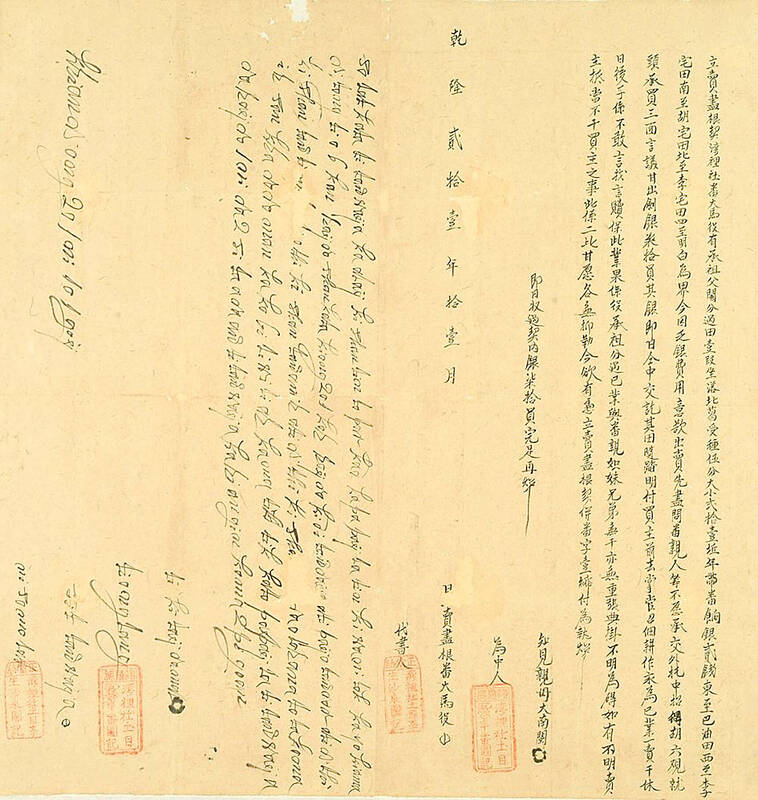

It should be noted that Junius preached in the Siraya language, writing it down in the Latin alphabet. This “Sinkan script” was later used in numerous documents, more than 100 of which survive today, providing an invaluable resource for those seeking to revitalize the language. He taught the villagers to write in it, and they continued to use it long after the Dutch left as documents were found dating to as late as the 1810s.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

A series of dramatic news items dropped last month that shed light on Chinese Communist Party (CCP) attitudes towards three candidates for last year’s presidential election: Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲), Terry Gou (郭台銘), founder of Hon Hai Precision Industry Co (鴻海精密), also known as Foxconn Technology Group (富士康科技集團), and New Taipei City Mayor Hou You-yi (侯友宜) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It also revealed deep blue support for Ko and Gou from inside the KMT, how they interacted with the CCP and alleged election interference involving NT$100 million (US$3.05 million) or more raised by the

A white horse stark against a black beach. A family pushes a car through floodwaters in Chiayi County. People play on a beach in Pingtung County, as a nuclear power plant looms in the background. These are just some of the powerful images on display as part of Shen Chao-liang’s (沈昭良) Drifting (Overture) exhibition, currently on display at AKI Gallery in Taipei. For the first time in Shen’s decorated career, his photography seeks to speak to broader, multi-layered issues within the fabric of Taiwanese society. The photographs look towards history, national identity, ecological changes and more to create a collection of images

At a funeral in rural Changhua County, musicians wearing pleated mini-skirts and go-go boots march around a coffin to the beat of the 1980s hit I Hate Myself for Loving You. The performance in a rural farming community is a modern mash-up of ancient Chinese funeral rites and folk traditions, with saxophones, rock music and daring outfits. Da Zhong (大眾) women’s group is part of a long tradition of funeral marching bands performing in mostly rural areas of Taiwan for families wanting to give their loved ones an upbeat send-off. The band was composed mainly of men when it started 50

While riding a scooter along the northeast coast in Yilan County a few years ago, I was alarmed to see a building in the distance that appeared to have fallen over, as if toppled by an earthquake. As I got closer, I realized this was intentional. The architects had made this building appear to be jutting out of the Earth, much like a mountain that was forced upward by tectonic activity. This was the Lanyang Museum (蘭陽博物館), which tells the story of Yilan, both its natural environment and cultural heritage. The museum is worth a visit, if only just to get a