For all the excellent works in English on Taiwan under Japanese colonial rule, there have been few (if any) monographs dedicated to Taiwanese women as imperial subjects.

Studies on the colonial government’s assimilation policy (doka) and, during World War II, its imperial subjectification efforts (kominka) overwhelmingly focus on male subjects.

As part of its southward expansion, the Japanese cultivated networks of Hoklo-speaking businessmen in Taiwan and southern China early in colonial rule. Later, producing committed soldiers became the main goal of education and government propaganda. These two entwined strands of imperial policy — expertly analyzed by Sheiji Shirane in Imperial Gateway (reviewed in Taipei Times, March 30, 2023) — ipso facto targeted men.

Likewise, as this book shows, colonial Taiwan’s social and cultural movements were male-dominated, and studies on this aspect of colonialism reflect this.

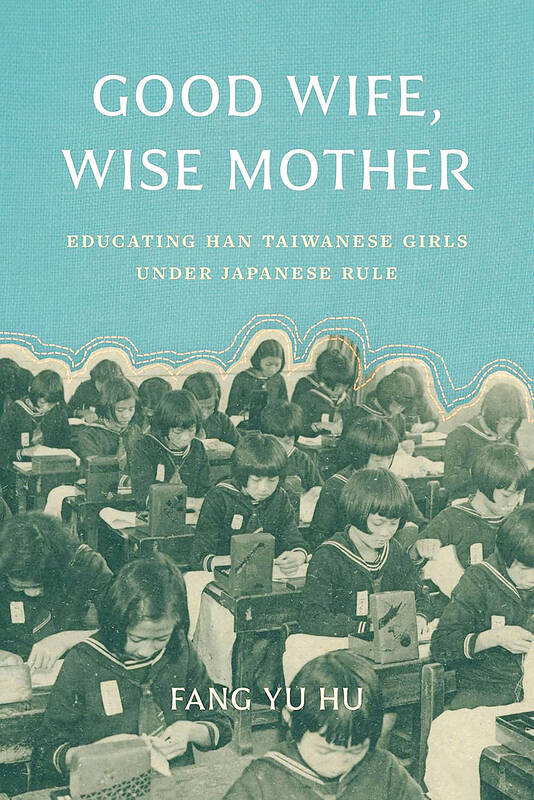

So, this book is overdue, and much of its analysis is valuable. Accompanying her arguments with illustrations from colonial textbooks, Fang Yu Hu shows how gender-specific values and practical knowledge were taught to Taiwanese girls. While there were limited depictions of women in early textbook editions, instances of female characters increased in later imprints. This reflected the increasing numbers of girls in education, writes Hu, an assistant professor of history at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.

ESTABLISHING ROLES

Enrollments among girls remained as low as 3,000 in 1915, but had increased almost tenfold by 1920, thanks to various strategies by the colonial administration, including home visits to convince mothers of the benefits of literacy, a higher maximum enrollment age and an increase in the number of female teachers. By 1930, more than 56,000 girls were enrolled; within a decade this figure had more than quadrupled.

Among the “gendered messages” communicated by the illustrations is feminine responsibility for sick relatives. One picture shows a young girl tending to her bedridden mother before, the text explains, going to get medicine for her. Another, titled “Doll’s Illness,” shows siblings role playing, with the brother dressed as a doctor and the sister cradling an ailing “infant.”

A third healthcare-related image portrays a boy ill in bed, as a doctor advises his mother that he remains sick because he did not immediately take medicine. Instead, his mother resorted to prayers to deities, unlike the boy’s friend, who suffered the same illness, but recovered fast thanks to a doctor’s prescription.

Reinforced by the physician’s bag and doctor’s garb, the message is clear: Western-style drugs should be trusted over folk superstitions, as part of Japan’s “scientific colonialism.” The brother in the role-playing scenario is dressed in a bowler hat, overcoat and spectacles, while his sister and the doll don traditional Taiwanese garments, emphasizing their primitiveness.

In general, Hu’s argument here seems sound for, as she points out, subsequent textbook editions continued to depict Taiwanese girls in Taiwanese attire, indicating that they “remained ‘backward’ and unchanged, perhaps resistant to change.” There was fear “of the potential damage that uneducated Taiwanese girls and women could do to make doka a failure …”

This was underscored by the campaign against foot-binding, criticized by educators in numerous journal articles as uncivilized and an obstacle to nurturing “strong and healthy mothers” who would, in turn, produce robust Japanese patriots.

Elsewhere, examples of gendered policy seem flimsy. It is hard, for instance, to discern the necessary gender-specificity of an illustration of a girl writing a letter and helping her mother understand postal services. The scene, Hu writes, “reveals that colonial officials expected educated girls to facilitate communication by using modern services.”

This seems obvious; but unlike the images of care giving, cooking and charity, one can easily imagine a young boy occupying the role of scribe and intermediary in the “Postal Service” illustration.

BOLD CLAIMS

If this seems insignificant, it’s symptomatic of a pervasive problem with the text, which sometimes manifests in bold but weakly substantiated statements.

In discussing the development of Taiwanese sociopolitical movements in the 1920s, for example, Hu concludes that activists could “anchor their critique of colonial rule in the purpose and the success of girls’ and women’s education.”

While she cites articles, written mostly by men but also some women, in Taiwan Minbao (originally Taiwan Seinen), the first independent Taiwanese periodical, her claim that colonial critiques were “anchored” in discussions of women’s education is a huge leap.

As is the case in academic works, the incessant ramming home of the thesis can grate — at points it feels like there’s a royalties deal tied to the reiteration of the “good wife, wise mother” mantra. In places, the repetition of the word “gender” also becomes wearisome. The following sentence, which refers to women’s memories of performing domestic chores for Japanese teachers, is indicative: “Their memories and nostalgia were gendered because of their expected gender roles, with their gender being connected to their labor.”

Yet, at its best, Hu’s examination of colonial gender norms is captivating and insightful. Regarding reports of sexual exploitation and abuse of female students, Hu observes that the teachers “represented the colonial authority while schoolgirls represented the Taiwanese people exploited by the Japanese.”

In her introduction to the short story collection A Son of Taiwan (reviewed in Taipei Times, July 14, 2022), Sylvia Li-chun Lin (林麗君) makes a related point about the marriage of a Taiwanese woman to a corrupt minor Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) official in “Potsdam Section Chief,” a tale by Wu Chuo-liu (吳濁流). The union, writes Lin, symbolizes Taiwan’s relationship with China. Interestingly, Wu’s treatment of female characters in his famed novel The Orphan of Asia is highlighted by Hu as an example of the conflicting attitudes of Taiwanese progressives toward the “good wives, wise mothers” paradigm.

A further parallel can be seen in analysis of the work of writer Li Ang (李昂), by scholar Wu Chia-rong (吳家榮), who sees sex between a Taiwanese female protagonist and her Chinese lovers as suggestive of “the original sin imposed on Taiwanese subjects” or “an act of betrayal … to the native soil.”

STARK CONTRASTS

Particularly incisive are the observations on the “social flattening” that the system produced during war mobilization when girls from working class backgrounds planted vegetables alongside classmates from privileged backgrounds. Overall, the system seems to have benefited girls from lower income families who acquired the literacy and skills needed for postwar employment, contributing to Taiwan’s development.

Gathered from interviews in Taiwan and the US, the recollections of these Japanese-educated women are fascinating, with many remembering the era fondly as time of camaraderie among girls across social strata and an era where discipline, manners and respect for authority were paramount.

Many, Hu found, contrasted Japanese moral education (shushin) and the order it created with chaos, corruption and injustice under the KMT. The disdain extended to the youth of today, who were branded self-centered and materialistic.

Ignoring the inherent discrimination of the colonial system — reinforced by the preexisting patriarchy — these women waxed lyrical about an era where education emphasized the collective good, fostering a “social harmony” they felt contemporary society lacked. In this sense, writes Hu, this passing generation of wives and mothers were as much defined by their Japanese education as their Chinese ethnicity.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern