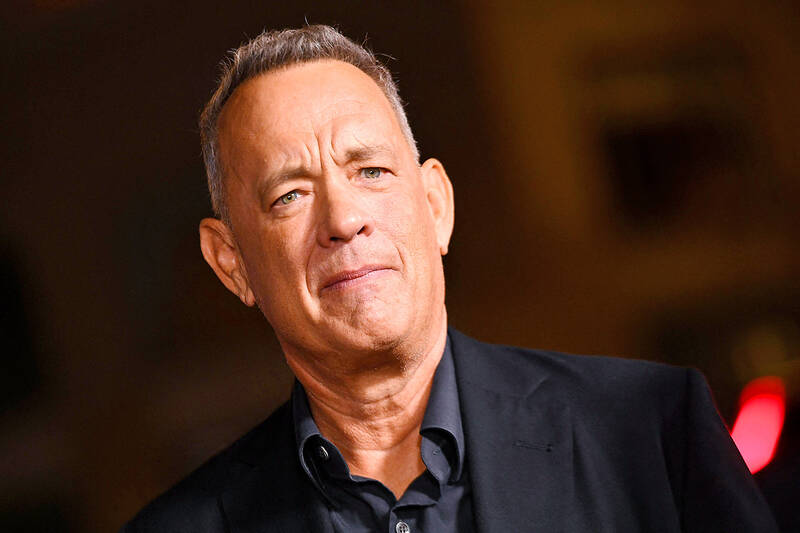

If you’re 34, watch out: Tom Hanks says 35 is the worst age. Why ask Hanks — delightful as he seems — as opposed to, say, the highly qualified global community of happiness psychologists and social scientists? Because he’s got a film out, duh — Here, which required him to be rejuvenated to various ages, including his dread mid-30s.

“Your metabolism stops, gravity starts tearing you down, your bones start wearing off [and] you stand differently,” Hanks told Entertainment Tonight. “You no longer are able to spring up off a couch.”

This is such a movie star answer. Hanks’ gripe is physical decline and yes, when your face, body and spring-off-a-couch-ability are how your worth is gauged, feeling that you’re physically degenerating must open up an existential abyss. For civilians, he’s wrong though: it’s 47.2. That’s when the US National Bureau of Economic Research concluded human unhappiness peaks. That finding in 2020 reinforced previous research on the “U-shaped happiness curve:” we start happy, wellbeing bottoms out at about 50, then we perk up again. The U-curve has been challenged, but seems robust; a 2021 review found “remarkably strong and consistent evidence across countries” of U-shaped happiness trajectories.

Photo: AFP

It makes sense. The base of the U is when layered responsibilities — a “club sandwich” of caring and working — collide with the awareness of finite possibility and the specter of failure (and death!). I should know — I’m 49. But I don’t like the idea of bumping along the bottom of a U-bend — we recently took apart the one under our sink and it was disgusting — and I also don’t think Hanks is right, so I conducted my own, highly unscientific survey.

The first thing I learned is, you have good conversations asking people their worst age. There’s a shared vulnerability to exploring your unhappiest times. They still live inside you, I think — remembering my two worst years (14 and 21) hurts me from chest to diaphragm, the place where a black hole of loneliness opened up then.

I also found that events can ruin any age, of course: illnesses, deaths and heartbreak, for the way they feel but also the way they distance you from your peers. Being as happy as your unhappiest child is an always, everywhere truth, and money worries can steal joy from every year and bleed into every area of your life.

Adjusting for those, though, clusters of better and worse ages emerge. No one seems to have been a truly unhappy toddler.

“I remember thinking: ‘I’m on a trike; what a life,’” my sister recalls gleefully of being three.

The first real collective nadir is mid-teens, including for two of my cheeriest male friends.

“The uncertainty and lack of agency were rough,” says one. “I was slightly friendless and terribly confused, surviving on library books and escapism,” says the other.

Women hated that time too: the mean girls, the mortification and the body horror. Those years play in my head as a violently multisensory kaleidoscope of leaking pads, razor burn, smells and spots.

A handful of people hated bits of their 20s, mostly evoking uncertainty: not knowing what to do, who you are, if it’s normal for your boss to throw a stapler at your head. Thirties can bite from either direction.

“No sleep, head down, anxiety, mourning loss of freedom,” said A of corporate life with young kids; unattached H hated “watching everyone else get engaged, married and starting to bring baby scans into the office.”

People do evoke bad 40s and 50s down the U-bend: those club sandwich pressures, “Is this it?” and damn hormones again (awful arriving, then awful departing).

There’s hope, though. It’s a small sample, but none of my older friends chose a year after their 50s; instead, I heard “More joy” and “Life gets better and better,” despite losses and bodies letting them down. A surprising number of people think their happiest age is right now — yes, now, in November 2024! They include Tom Hanks — he said he would “rather be as old as I am.”

Me too, actually. I think lots of us tend to assume we’re past the worst, which suggests that we’re optimists. That’s good — we’ll need to be.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

As I finally slid into the warm embrace of the hot, clifftop pool, it was a serene moment of reflection. The sound of the river reflected off the cave walls, the white of our camping lights reflected off the dark, shimmering surface of the water, and I reflected on how fortunate I was to be here. After all, the beautiful walk through narrow canyons that had brought us here had been inaccessible for five years — and will be again soon. The day had started at the Huisun Forest Area (惠蓀林場), at the end of Nantou County Route 80, north and east

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the