While global attention is finally being focused on the People’s Republic of China (PRC) gray zone aggression against Philippine territory in the South China Sea, at the other end of the PRC’s infamous 9 dash line map, PRC vessels are conducting an identical campaign against Indonesia, most importantly in the Natuna Islands.

The Natunas fall into a gray area: do the dashes at the end of the PRC “cow’s tongue” map include the islands? It’s not clear. Less well known is that they also fall into another gray area. Indonesia’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) claim and continental shelf claim are not coincident in that area, as Australian security and defense expert Euan Graham pointed out on X (Twitter) last week. “China knows how to exploit a grey zone when it sees one,” he observed.

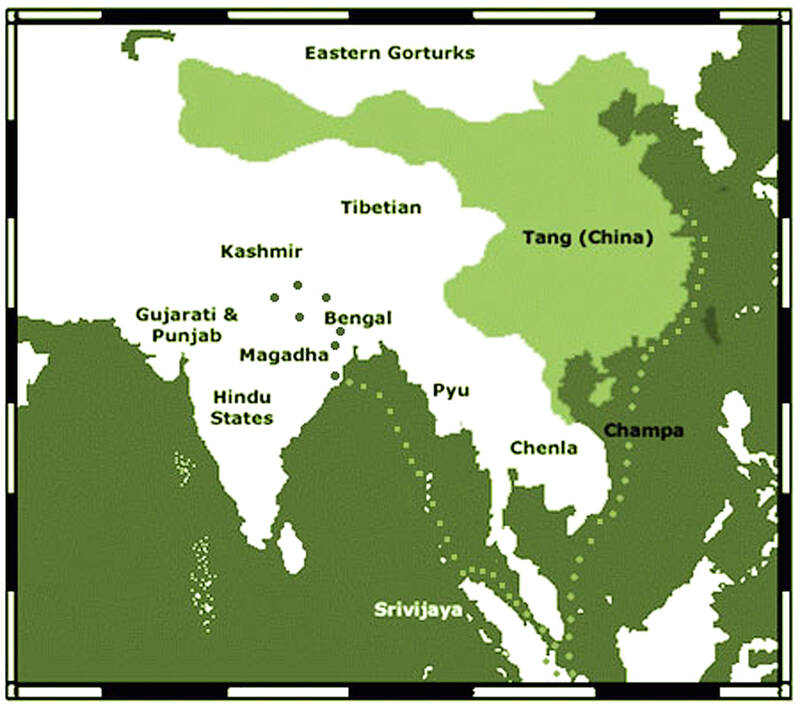

The Natuna Regency, the Indonesian administrative name for the region, contains “at least” 154 islands, 127 of which are uninhabited, according to Wikipedia. As always, after supplying some facts to orient the reader, Wiki then moves on to the history, where, in the very first sentence, we are treated to an amazing nonsense artifact: “The Natuna Islands were discovered by I-Tsing in 671 A.D. and mentioned throughout his notes in A Record of Buddhist Practices Sent Home from the Southern Sea.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

I-Tsing (Yijing, 義淨), was a Tang Dynasty Buddhist scholar whose travel writings are important sources of information on the routes between India, China and the kingdoms of what is today Malaysia and Indonesia. He is famed for translating Buddhist texts, and for his commentaries on the state of Buddhism in the places he visited. He did not, however, “discover” anything. He was a monk, incapable of operating a ship or recording navigational information. The only difference between himself and the cargo aboard the vessels he rode on was that he was alive.

Anyone who wants to see what Wikipedia would be like if PRC propagandists had unlimited access need only visit Quora, which on matters related to the PRC is nigh-on useless, thanks to the 50-cent brigade. But despite Wikipedia’s generally sturdy editing work, pro-PRC statements and frames like this creep in. As the first sentence in the “history” section, it subtly supports the PRC claim to the area by attributing “discovery” to someone from China.

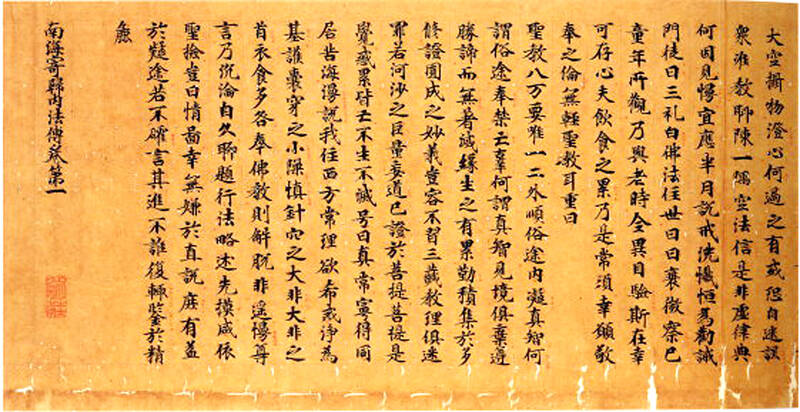

YIJING’S ACCOUNTS

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

As history the statement is absurd. Tang-era ships did not play the routes between India, China and southeast Asia. In the seventh century that was the domain of Near Eastern and Indian seafarers who had been part of extensive trade networks across seas of India and southeast Asia for at least a millennium. Yijing himself records that he left from Guangzhou aboard a Persian vessel and sailed to Srivijaya in what is now Indonesia. Along the way he kept running notes on the locations he passed, on their customs and their adherence to Buddhism. It is obvious from both his notes and his occasional references that the islands he passed were inhabited (as many are today).

Yijing’s notes are merely the oldest surviving written account of the area. Since tablets with writing from the Srivijaya kingdom are known from shortly after his time, it is highly plausible that even that state is simply the luck of archaeological practice. Sooner or later earlier inscribed objects discussing the area will be unearthed.

However, there must have been written accounts galore. The loss of so much of the Greco-Roman classical corpus is generally mourned, but the loss of writings from southeast Asia must have been just as great. Yijing records the habits of Buddhist monks wherever he went, describing in minute detail their variations in habits. Buddhism is a text-based religion, and must have been transmitted from literate to literate. With the thousand monks then in residence, Yijing himself extols Srivijaya as an excellent place to study Buddhist texts. All lost, today.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Yijing admits he is uncertain of the size of the area, and remarks that the merchants who regularly plied these waters would know. Scholars and dilettantes of our own age tend to focus on the literati of a bygone age, a subtle class solidarity that reaches across time, distorting what it touches. Yet, also lost is another enormous corpus of records: the rutters used by local pilots to navigate.

A rutter is a set of notes a navigator compiles about routes, landmarks, the sea and its currents and tides, the sea bottom, astronomy, climate, wind conditions and other aspects of navigation and port activities. The word in English comes down from Arabic, indicating the importance of Arab rutters in the development of similar western texts. The Persian ship that took Yijing to Indonesia must have had a set of rutters describing the route and its associated land masses in detail, developed over numerous voyages.

HISTORICAL PROPAGANDA

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

These conclusions about Yijing are also true of every other “historical link” invented or appropriated by the PRC for its historical propaganda. The PRC often cites the scribblings of its literati in their travels as legitimating texts for its expansionist claims, appealing to the historical bias that treats literati as a superior source of knowledge. The truth is that the Chinese literati, landlubbers traveling long-established routes, were always the last to know of a place. Centuries before them, the masters of the ships on which they traveled already knew the routes and recorded them in their rutters. Most of these have been lost.

One of the ways our social biases toward the literate and toward history as the story of the upper class help the PRC erase the past is that we forget the existence of documents like rutters, and the non-Han sailors who compiled them (going all the way back to the Austronesians and Negritos who first settled southeast Asia). PRC discourse wants us to focus on the Chinese and their activities, which not only moves them into prominence, but conceals the expert navigators who carried them and their trade goods from one place to another.

Since mid-October a Norwegian survey ship contracted by Indonesia has been in the Natunas performing a fossil fuel survey, and the PRC coast guard has parked a ship there to shadow it. Indonesian navy vessels have been unable to eject the PRC ships and clear the area. Each time the Indonesian authorities have reported ejecting them, the PRC coast guard has returned. As the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) observes, though PRC vessels and the Indonesian coast guard have clashed before, this is the first time the Indonesian government has been so prompt in releasing information on PRC activities.

Expect the Natunas, and Yijing’s name, to come up more often.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on