Nov. 4 to Nov. 10

Apollo magazine (文星) vowed that it wouldn’t play by the rules in its first issue — a bold statement to make in 1957, when anyone could be jailed for saying the wrong thing.

However, the introduction to the inaugural Nov. 5 issue also defined the magazine as a “lifestyle, literature and art” publication, and the contents were relatively tame for the first four years, writes Tao Heng-sheng (陶恒生) in “The Apollo magazine that wouldn’t play by the rules” (不按牌理出牌的文星雜誌).

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

In 1961, the magazine changed its mission to “thought, lifestyle and art” and adopted a more critical tone with the joining of outspoken essayist Li Ao (李敖), who boasted in a later essay that prior to his arrival, Apollo “did not incite trends, did not create talking points, did not affect public opinion and did not make the old fogeys’ blood boil.”

That December, Apollo ran then-Academia Sinica president Hu Shih’s (胡適) speech, “Social change necessary for the growth of science” (科學發展所需要的社會改革), which criticized dated Eastern traditions and ways of thinking that he believed were holding the nation back.

“This is no blind condemnation of the ancient civilizations of the East, nor blind worship of the modern civilizations of the West,” Hu emphasized, but this article ignited an intense battle of words regarding Eastern versus Western ideals that lasted for years and left an impression on many young intellectuals.

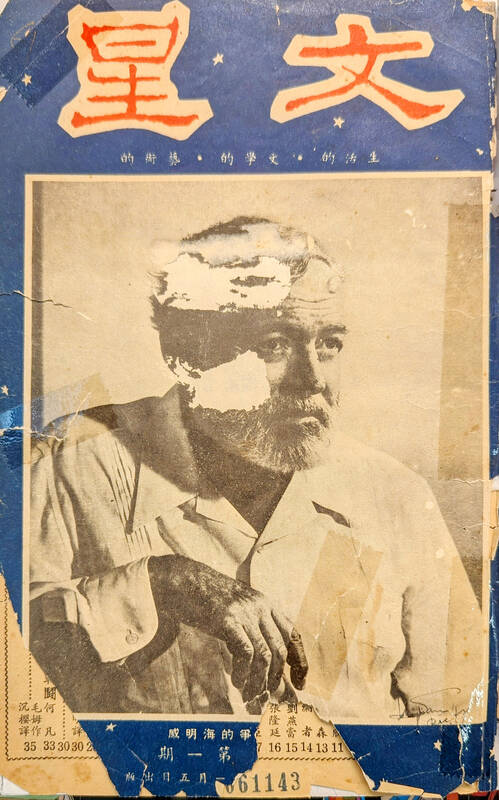

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

In 1965, Apollo attracted the attention of government censors, who confiscated three issues that year. The Dec. 1 edition directly slammed the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) for abuse of power and authoritarianism. The magazine was banned for a year, but further attempts to reinstate it were rejected until its brief revival in 1986.

GENERATIONAL STRUGGLE

Apollo was founded by Hsiao Meng-neng (蕭孟能), whose father Hsiao Tung-tzu (蕭同茲) was a communications officer for the KMT who in 1932 relaunched the Central News Agency (CNA) as a news service separate from party headquarters. After relocating to Taiwan in 1949, the younger Hsiao set up a bookshop in Taipei that reprinted Western publications and carried foreign magazines.

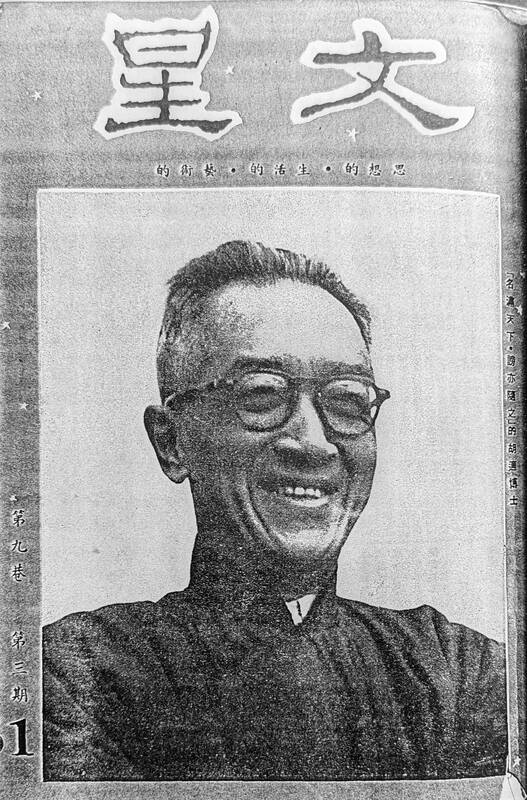

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

He launched Apollo with former CNA Taipei director Yeh Ming-hsun (葉明勳) as publisher, and noted literary couple Hsia Cheng-ying (夏承楹) and Lin Hai-yin (林海音) (see: “Taiwan in Time: The miner of literary gems,” Nov. 26, 2017) as chief editors.

Current Taiwan Fact Check Center CEO Eve Chiu (邱家宜) writes in “Apollo and the 1962 Chinese-Western culture debate” (文星與1962年的中西文化論戰) that at first, “not playing by the rules” likely just referred to being bold enough to start a publication when scores of magazines were shutting down. They lost money for the first three years, broke even in the fourth and finally took off after shifting gears in late 1961. Soon, they were selling up to 12,000 copies per issue. In mid-1962, they doubled the pages from 40 to 80 and also doubled the price from NT$4 to NT$8.

It was a precarious time to amp up the editorial rhetoric; in 1960, Free China (自由中國) was shut down for advocating the launch of an opposition party and its founder Lei Chen (雷震) was thrown in jail for actually attempting to do so. Chiu writes that this event, coupled with the growing hopelessness in “reclaiming China,” left Taiwan’s young mainlander intellectuals feeling disillusioned and uneasy, even becoming resentful against the older generation who held onto power, refused to own up to their failures and silenced those who spoke out.

Lei’s arrest left little room for political discourse, and with few avenues to express their frustrations, things finally boiled over. Chiu writes that instead of a cultural struggle, the debate was more of a generational struggle as the young writers pushed back against their elders, who in their eyes lost China to the communists because they stubbornly refused to modernize and adopt Western ideas. Although there was a long way to go, Chiu writes that this was the beginning of the loosening of the KMT’s authority over national ideology.

CHAMPIONING HU

Hu was from the older generation, but he had been a proponent of modernization since the 1920s. In fact, his arguments were nothing new; his speech mainly reemphasized the points he made 35 years earlier that Easterners needed to let go of their superiority complex and welcome the beneficial parts of Western culture. Science and technology are not merely for material gain, but are “highly idealistic and spiritual values” that aim to better the human condition by eradicating “ignorance, superstition and slavery to the forces of nature,” he said.

Critics found fault with his notion that such values are “sadly underdeveloped in Oriental civilizations.”

“What spirituality is there in a civilization that tolerated such cruel and inhuman institutions such as footbinding for women for over a thousand years?” he asked. “What spiritual values are there in a civilization that considers life as painful and not worth living and glorifies poverty and mendicancy and sanctifies disease as an act of the gods?”

Philosopher Hsu Fu-kuan (徐復觀) was the first to strike back, calling Hu in an editorial the “shame of all Easterners.” In response, Apollo put Hu on the cover of the next issue with Li Ao penning a mostly positive profile of him. It included several pieces rebuking Hsu, one calling him an “antiquated patriot.” The following issue came out swinging with Li Ao slamming a number of prominent scholars, while other writers defended Hu’s ideas. Hu died of a heart attack in February 1962.

This topic was still ongoing in the final issue, which included a piece criticizing the classism in Confucianism and another discussing how traditional Chinese culture impedes scientific development. It also included a scathing editorial, presumably penned by Li, that objected to government interference with previous editions and demanded the KMT restore constitutional rule and democracy.

Of course this did not sit well with the authorities. They raided the office and confiscated the freshly-printed copies of the following issue. Both the magazine and bookstore shut down.

BRIEF REVIVAL

Twenty years and eight months after its initial demise, Apollo came back to life on Sept. 1, 1986.

“What sort of spiritual nourishment can we provide to today’s youth?” Hsiao asked in the editor’s words. “The sheer enthusiasm I felt 20 years ago to ‘not play by the rules’ has been reignited.”

It was a completely different Taiwan by then; the KMT’s one-party rule would end later that month and martial law would be lifted the following year. But the same questions of modernization and social change endured, wrote the editorial board, who stated their goal to introduce all sorts of global trends to the readers while exploring what it means to be “Chinese” within this context.

Tao writes that the contents of the new Apollo were higher in quality and more mature, but it failed to connect with young readers. Hsiao ended the magazine again in June 1988, citing financial concerns and his own health.

“In this highly politicized era, there seems to be fewer people who care about culture and ideology from a long-term perspective,” he writes in the final issue. “While Taiwan has become more open and lively on the surface, the entire society has become embroiled in political gossip. Star politicians have become idols and heroes, and political scandals and societal clashes have become the main source of stimulation for the masses.”

“It seems that society is moving further from our ideals. That’s the real reason Apollo can no longer continue.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth