A modern form of “grave robbery” is flourishing online, experts say, as bone collectors exploit legal loopholes to buy and sell human remains.

In Australia, where it is illegal to buy or sell human remains (albeit with some exceptions), people sell photographs of the remains then add the bones as a “gift.”

While people may trade in remains to make money, some experts say others with the macabre habit of collecting them do so for power, control and identity.

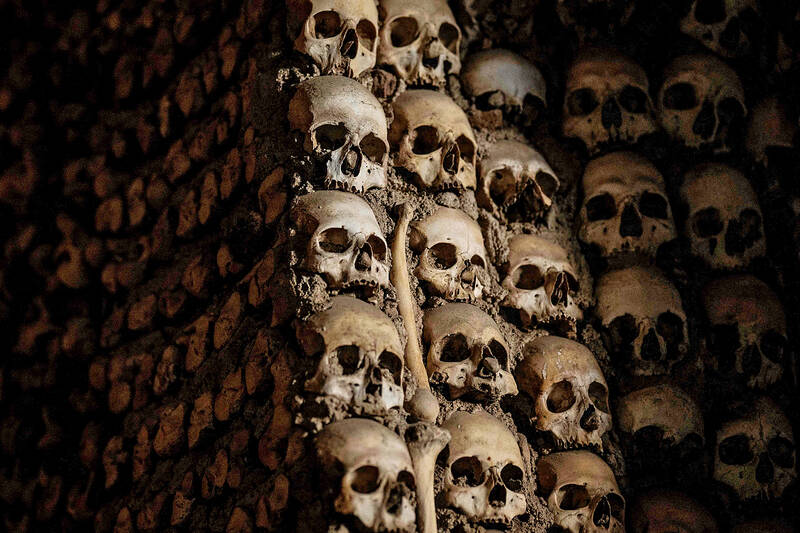

Photo: AFP

BIG BONE COLLECTIONS

Damien Huffer, the author of These Were People Once: The Online Trade in Human Remains and Why It Matters, says some individuals have collections that can rival museums, and Australia’s laws are not sufficient to stop them.

“The laws are quite inconsistent from the state and territory level, and certainly in between countries,” he says.

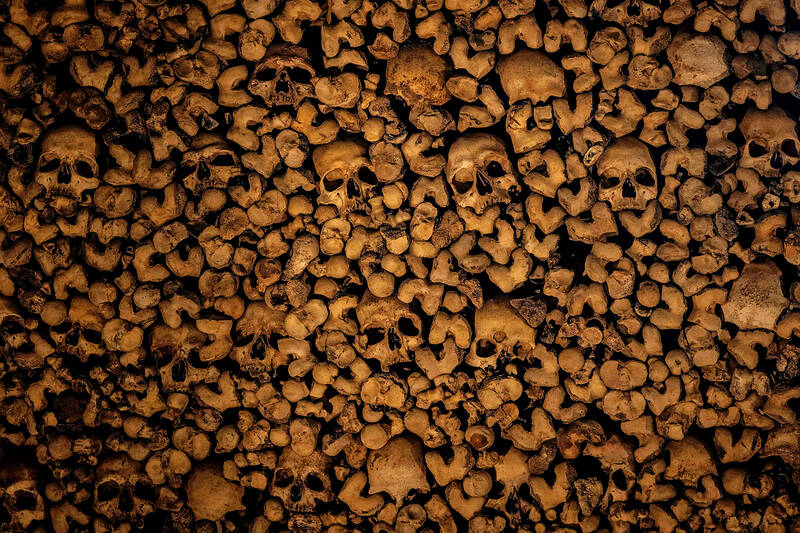

Photo: AFP

“And now so much is online — [it] could have been a very niche little subculture of the antiquities trade if the Internet never existed, but because of the way the world works, what once was niche has blown up.”

Huffer, an honorary research fellow at the University of Queensland and co-founder of the Alliance to Counter Crime Online, has studied an Australia-specific tactic, where photographs of human remains are offered for sale with the bones included as a “gift” to get around laws about buying and selling.

Bone traders also use emojis, codewords and hashtags to connect with each other and evade detection.

Photo: AP

They might discuss “oddities” that are “hooman,” for example. In a paper published in the Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology, Huffer describes one person posting: “Would someone gift (wink emoji) … a man/woman femur or two?”

Another says: “Oddlings! I have something … special available. You will receive the photo plus a free vintage medical specimen … real (bone emoji). (Ship emoji) inc. payment plans available.”

And it’s not just skeletal remains. Cremains — bone fragments left over after a body is cremated — and wet specimens such as organ slices are also traded.

ILLEGAL

It has been illegal to sell human remains since 1982, when human tissue legislation was rolled out across the states and territories. But many doctors received real skeletons during their training and so collections of bones lingered on, sometimes turning up in sheds and deceased estates.

“Medical” specimens have a kind of legitimacy because many were imported before law changes made importation of human remains illegal and due to limited exemptions for medical items.

Huffer says bones in Australia had often arrived decades ago from India, Bangladesh and elsewhere. He says they were “the unclaimed, the low caste, the poor, who were taken, stripped down, sanitized [and] wired up.”

South Australia police are investigating the alleged sale of human skulls by auctioneers Small and Whitfield: one “medical skull” sold for US$600, another “with open cranium and a few vertebrae” and the “lower jaw missing” was snapped up for US$1,500.

A police spokesperson said the auction house was cooperating and “to date no offenses have been identified.”

“Determining the origins of all of the remains can be a complex and protracted process,” the spokesperson says.

The managing director at Small and Whitfield, David Kabbani, says they have received about three or four skulls over the past 20 years that weren’t medical specimens.

“We know the difference as auctioneers between a genuine medical piece, a skull used for medical purposes as opposed to something that’s come from nobody and nowhere, that we hand in [to police],” he says.

Asked about the origins of the medical pieces, Kabbani says they come from retired doctors, who were legally provided them as part of their training when it was legal to import them. He says there was plenty of uncertainty about the law as it stands, including among the police.

“On many occasions when we’ve had questions about selling these things, we’ve rung the police to get an answer and they’re unsure,” he says.

Maeghan Toews, an Adelaide Law School lecturer who teaches medical law and ethics says state and territory legislation prohibits buying and selling human tissue, from living and deceased bodies.

“There are exceptions, however, which is where some of the uncertainty arises,” she says.

Toews points to the SA Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1983, which allows the sale or supply of tissue “if the tissue has been subjected to processing or treatment and the sale or supply is made for use, in accordance with the directions of a medical practitioner, for therapeutic, medical or scientific purposes.”

“One point of confusion,” she says, “is what counts as a ‘scientific purpose,’ which is not defined in the act.

“Another point of confusion … is the extent of ‘processing’ that is needed to transform the tissue into sellable goods.

“Finally, while the requirement that the sold tissue be used ‘in accordance with the directions of a medical practitioner’ makes sense for therapeutic and medical uses, whether or not this applies (or should apply) to ‘scientific purposes’ is also unclear.”

The Australian Law Reform Commission started an inquiry into the state and territory laws in August.

The inquiry will perhaps clear up some of these points of confusion, she says.

MACABRE COLLECTOR SUBCULTURE

There is a long history of collecting human parts, as war trophies and in museums in the name of science (often racial science).

Modern day collectors might explain their macabre habits as being out of an appreciation for human biology, or curiosity or because of the gothic aesthetic, Samantha Waite says, but she believes there could be a different reason.

Waite, a former hospice psychotherapist, now runs Taboo Education, which works to demystify death.

She says there are various reasons people get into the bone trade, and often it’s tied up with wanting to prove their identity to, and be accepted by, a specific subculture of collectors.

“A lot of them tend to not interact much with the living, this is their way of telling themselves they’re still interacting with humans,” she says. “And there can be a feeling of power.

“Psychology-wise, specific parts of the body tend to mean certain things and a skull is definitely one of power.”

Huffer says people should think about how they would feel if their loved ones were “taken out of their place of rest, dug up, circulated and recirculated with price tags.”

It’s dehumanizing, and perpetuating colonial violence, he says.

“The bottom line is no one who entered the medical bone trade … none of them ever consented to being used as such,” she says.

“Who knows, [there might be] hundreds of thousand of examples on the market, from the days before consent forms, paperwork – it’s just another form of grave robbery.”

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the country’s other political groups dare not offend religious groups, says Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟). “It’s the same in other democracies, of course, but because political struggles in Taiwan are extraordinarily fierce, you’ll see candidates visiting several temples each day ahead of elections. That adds impetus to religion here,” says the retired college lecturer. In Japan’s most recent election, the Liberal Democratic Party lost many votes because of its ties to the Unification Church (“the Moonies”). Chen contrasts the progress made by anti-religion movements in

Last week the State Department made several small changes to its Web information on Taiwan. First, it removed a statement saying that the US “does not support Taiwan independence.” The current statement now reads: “We oppose any unilateral changes to the status quo from either side. We expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” In 2022 the administration of Joe Biden also removed that verbiage, but after a month of pressure from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), reinstated it. The American

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislative caucus convener Fu Kun-chi (傅?萁) and some in the deep blue camp seem determined to ensure many of the recall campaigns against their lawmakers succeed. Widely known as the “King of Hualien,” Fu also appears to have become the king of the KMT. In theory, Legislative Speaker Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) outranks him, but Han is supposed to be even-handed in negotiations between party caucuses — the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) says he is not — and Fu has been outright ignoring Han. Party Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) isn’t taking the lead on anything while Fu

Feb 24 to March 2 It’s said that the entire nation came to a standstill every time The Scholar Swordsman (雲州大儒俠) appeared on television. Children skipped school, farmers left the fields and workers went home to watch their hero Shih Yen-wen (史艷文) rid the world of evil in the 30-minute daily glove puppetry show. Even those who didn’t speak Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) were hooked. Running from March 2, 1970 until the government banned it in 1974, the show made Shih a household name and breathed new life into the faltering traditional puppetry industry. It wasn’t the first