Why are so few biographies of famous figures written by their close descendants? After all, they have the best access to documents, diaries and letters, and also access to people involved in the subject’s life. Perhaps it’s because there are family secrets and fault lines best left silent; and there might also be resentments — the rise to becoming a notable figure often involves sacrificing one’s family.

Young American woman Kim Liao found this out for herself when she started pursuing the story of her paternal grandfather, Thomas Liao (廖文毅). He was a prominent early Taiwanese independence activist, but within the Liao family in the US, his name had largely been erased.

The seed for Kim’s adventure of discovery was, back in the year 2000, while still in high school, reading George Kerr’s Formosa Betrayed (1965). Kerr was vice consul of the US diplomatic mission in Taipei from 1945 to 1947 and an eyewitness to the 228 Incident and the mass arrests and executions that followed. One passage of Kerr’s book in particular jumped out:

“On Sept. 1, 1955, Liao’s Party formed a Commission of 33 members. . . . In the following year, on Feb. 28, 1956, this ‘Congress’ inaugurated a ‘Provisional Government.’ Not unexpectedly, Dr. Liao was named First President.”

Kim describes her shock at reading this: “Hold on a minute — what the what? My grandfather had not only risen to lead an oppositional political movement but also had been elected first president of a government somewhere?... This has to be wrong. Surely someone would have told me.”

She was intrigued, but also paralyzed with confusion and the fear of causing family strife.

“For the Liaos, family was a structure held together with glue, the bonds of blood and the seal of silence,” she writes.

A decade later, curiosity had asserted itself, and she came to Taiwan on a Fulbright scholarship to research and write about the Thomas Liao story.

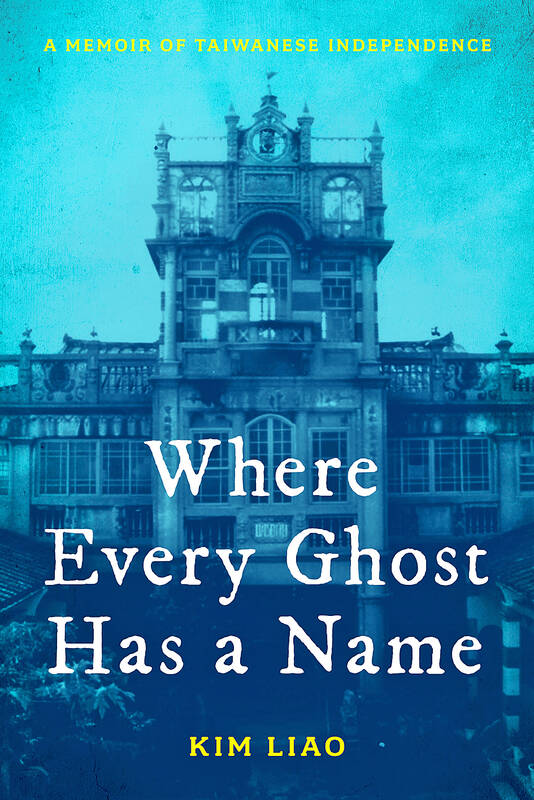

The resulting book, Where Every Ghost Has a Name: A Memoir of Taiwanese Independence, follows detective-procedural fashion Kim’s discoveries in Taiwan, visiting important places and talking to people — both relatives and important political figures, Peng Ming-min (彭明敏) for example; these chapters are intertwined with those following Thomas Liao and his family.

Thomas Liao (1910–80) was the son of a wealthy Presbyterian landowning family in Siluo Township (西螺) in Yunlin County. He went abroad in the 1920s to study — in Japan, China and ultimately the US, where he acquired a PhD in chemical engineering and a Chinese-American wife called Anna. After World War II, as one of the educated Taiwanese elite, Liao was looking to play a part in rebuilding Taiwan, as was his older brother Joshua, another PhD holder from the US.

Thomas and Joshua both pushed for democratic rule of Taiwan after the handover from Japan, but attempts to participate in the process were stymied by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT); the brothers were left to express their ideas in a magazine they founded called Qianfeng [Vanguard], which made them targets come the 228 Incident. Luckily, Thomas Liao had left Taiwan just days before. He stayed for a time in Hong Kong, and then in 1950 moved to Japan, where he founded the Taiwan Democratic Independence Party; on Feb. 28, 1956 he was elected president of the Republic of Taiwan Provisional Government.

By this time, his wife, Anna, who had been taking care of the children, had already moved to the US. She had given him a choice — family or the fight for Taiwan independence. He chose the latter. It was a sacrifice for Liao that did not ultimately pay off for himself — he would renounce his activism for independence in a much publicized return to Taiwan in 1965 and received a full pardon by then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石). Liao had, though, through his writing and actions inspired a generation of Taiwanese activists. He was not, however, a hero to his wife and children.

Kim Liao gives fascinating details about the KMT’s multi-pronged campaign to get her grandfather to return, involving dirty tricks, one of which was giving an Uncle Suho (Liao Shi-hao, 廖史豪, Thomas Liao’s nephew) a death sentence.

Kim Liao was based in Taipei during her year of research but traveled widely, especially to Yunlin County’s Siluo Township, the Liao family hometown, “a town where every ghost had a name.” She visited the infamous prison on Green Island and other White Terror sites.

Every Ghost is a non-fiction work but contains elements of fiction; there are imagined conversations and thoughts. For example, there’s a scene where Anna, an American citizen, visits George Kerr at the consulate after the 228 Incident:

“‘Okay,’ George said, getting up from the desk and marching briskly to a cabinet in the corner of the room. ‘Here’s what you do. Take this American flag.’ He took out a triangular folded cloth bundle and handed it to Anna. ‘Fly this American flag over the door of your house. That’s what we’ve been instructing our American employees and associates to do.’”

There will be history purists who will bristle at this kind of imaginative writing. However, it’s done well and it works. End notes give the sources, such as interviews and letters.

In fact, this is one of the best books I’ve read on Taiwan’s 20th-century history. The writing is engaging, the mix of personal and historical information spot-on, as are the way the multiple threads unfold.

If there is an unstated lesson in this biography, it might relate to the author rather than the subject; do not delay in getting down information from participants in recent history. Kim managed to catch many sources just before they died. Her father, an early critic of the project — “Don’t write about the family” — who changed his mind, passed away before Kim could show him the book. Record your family history, even if it is hard work and a little uncomfortable, before it’s too late.

John Ross is the author of ‘Taiwan in 100 Books,’ and co-host of the Formosa Files podcast.

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of