Taiwan’s AI industry will generate over NT$1 trillion by 2026, according to projections by the National Development Council (NDC), based largely on Taiwan’s dominance in semiconductor manufacturing. But the goal to make Taiwan Asia’s leading AI hub, or “AI island” in the words of President William Lai (賴清德), depends on several factors, not the least of which is to pull 120,000 AI professionals out of a magic hat. By 2028.

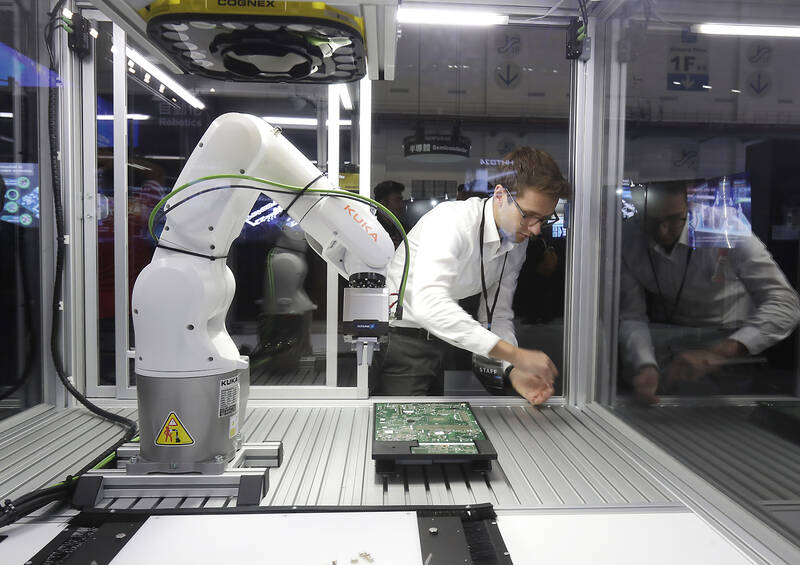

The global competition to lead the AI sector is like an AI Olympics. Taiwan possesses a sophisticated semiconductor supply chain, state-of-the-art facilities and advanced infrastructure that make it a premier training ground for the real AI Olympic athletes — tech giants like Nvidia, Advanced Micro Devices Inc (AMD), Google and Microsoft. Many are already here, again largely due to Taiwan’s semiconductor supply chain. However, without skilled trainers and coaches (AI professionals), will these tech giants stay?

If we ignore the political and economic threats from China, Lai’s vision for Taiwan to become the Asian AI hub hinges on three conditions: constructing energy efficient data centers, ensuring a stable and largely renewable energy supply and developing a strong AI talent pool.

Photo: Reuters

The first is a relatively straightforward engineering challenge. The second and third involve deeper infrastructural issues that may be insurmountable. I previously questioned whether Taiwan has the power to compete in the AI Olympics, but an equally difficult question is whether it has the talent to compete.

It is important to be clear from the start that it will be impossible for Taiwan to develop its own sufficiently large AI workforce. The low birth rate of 5.8 per 1,000 people is shrinking the workforce in an already aging society, and Taiwan’s relatively low salaries for professionals has fueled a brain drain for decades.

This means that even recent efforts by organizations like the Taiwan AI Academy to train more AI specialists and technicians will fall ridiculously short of industry needs. The critical shortfall of AI specialists in fields from machine learning and data science to software development and hardware engineers cuts off AI sector growth at the knees.

Photo: Reuters

What this means is that recruiting talent from other countries is inescapable. And for this, there are two main targets: 1. AI students, 2. AI professionals.

EDUCATING LOCAL AND FOREIGN TALENT IN TAIWAN

Education is part of the proposed solution. This is a longer-term initiative to increase enrollment of foreign students in AI-related disciplines. The Taiwan AI Academy and university partnerships, such as Chang Gung University’s all-English AI master’s program, focus on industry-relevant training and offer full scholarships and internships with tech giants like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) and MediaTek to build and retain talent in Taiwan.

Photo: AP

In theory, this sounds good. In practice, perhaps not. Taiwan does not have a great track record for reforming education, which is one of the nation’s most conservative institutions.

Challenges here will involve the education system’s emphasis on rote learning and the implementation of English as a medium of instruction, for both instructors and Taiwanese students. Efforts like the Bilingual 2030, an initiative that Lai himself introduced in 2014 when he was mayor of Tainan, have so far achieved limited results. For high school graduates, only 20 percent have reached a high intermediate proficiency. The number is probably substantially less for the science and engineering population, who tend to be stronger in math subjects as opposed to language ones. This low English proficiency will impact both foreign students in international programs and foreign workers in international tech companies.

However, even if AI education initiatives meet Taiwan’s AI Academy estimates of 10,000 AI trainees after three years, this number pales in comparison to the actual projection of 120,000 AI professionals by 2028. And in the best case scenario, reforms for hands-on, interdisciplinary learning will take time to show any significant impact.

HIRING FOREIGN TALENT

Recruiting foreign talent is what will make up the remaining talent deficit of over 100,000 AI professionals in the next few years. To attract these international experts, Taiwan has expanded its Gold Card visa program and offers extended work permits and residency options. And according to 104 Job Bank (104人力銀行) statistics, the average salary for AI positions has also risen significantly, from NT$41,000 (US$1,299) to NT$57,000, reflecting a 38 percent increase due to the high demand for skilled professionals. The salaries are likely more for foreign recruited engineers and technical specialists.

Despite these efforts, Taiwan faces intense competition from other tech hubs like Silicon Valley and Singapore, which provide higher salaries and more attractive incentives, making it difficult for Taiwan to draw the necessary talent. Data scientists in Taiwan, for example, can expect to make only a third of their US counterparts’ salary.

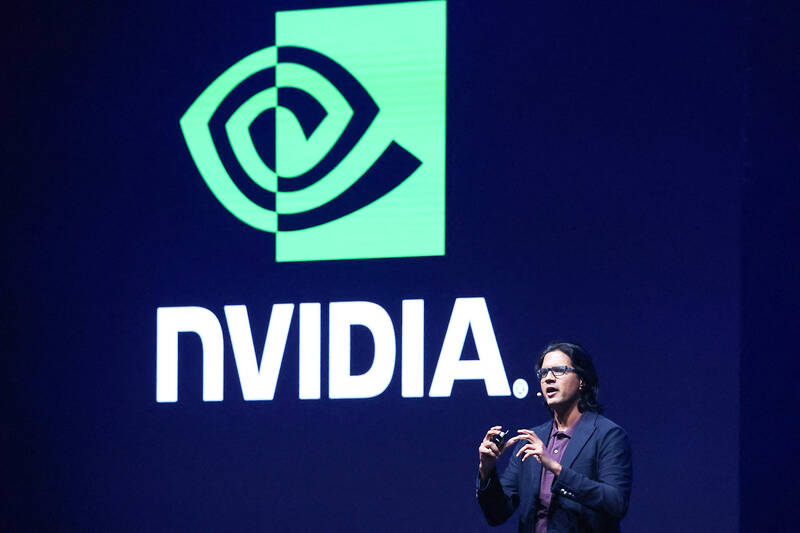

To address its talent shortage, Taiwan has asked major tech companies such as Nvidia and AMD to establish R&D centers on the island to bring their own skilled engineers. Minister of Economic Affairs J.W. Kuo (郭智輝) proposed that tech companies looking to establish R&D centers in Taiwan should recruit at least 500 engineers from abroad for every 1,000 they need in Taiwan. However, the global shortage of AI professionals means that even these companies are feeling the recruitment pinch. IT Brief UK reports that 35 percent of global enterprises are suffering from a “critically low supply of AI expertise.”

BETTING ON INDIA

The development council has set its sights on India, which has the second largest AI professional population outside of the US. Taiwan is specifically targeting Bangalore, India’s tech hub, in an effort to attract AI talent through LinkedIn marketing campaigns and partnerships with Indian universities.

However, the demand for AI talent in India is increasing and is expected to grow from 600,000 to 650,000 in 2022 to more than 1.25 million in 2027, according to a report by Deloitte. With India’s AI market growth estimated at 25–35 percent per year, India suffers from a similar demand-supply gap in the talent pool and will need to redouble efforts on upskilling existing talent.

But the reality is that for most Indian engineers who want to leave India, Taiwan will fight a losing battle against countries like the US and Singapore for the best salary, benefits and quality of life.

WHAT TAIWAN SHOULD DO

Taiwan is working to bridge its AI talent gap. But it needs more effort in three areas if it wants to create a real solution instead of the illusion of one.

First, more international training programs are needed. International students will be attracted to educational opportunities in Taiwan with high quality AI programs, scholarships, internships with tech giants like TSMC, Nvidia and Google. Better promotion and visibility can be achieved through collaborations with international research centers in places like the US and India. An influx of international students will also be a life saver for many universities struggling to meet enrollment needs.

Second, Taiwan must offer more competitive salaries, streamlined visa processes like the Gold Card program, citizen rights and international work and living environments that appeal to international AI professionals and to encourage them to stay.

Lastly, a more developed and focused Bilingual 2030 initiative will be critical in creating international environments in colleges, companies, government agencies and in society in general, to make Taiwan more accessible, comfortable and hopefully enjoyable, for both foreign students and workers.

By aligning these efforts, Taiwan can make the first steps toward finding coaches and trainers it needs to compete in the global AI Olympics. And in many ways, the AI labor shortfall is a testing ground for solving Taiwan’s larger — and impending — societal and demographic issues with its rapidly shrinking birth rate and workforce and rapidly aging society.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Last week the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) said that the budget cuts voted for by the China-aligned parties in the legislature, are intended to force the DPP to hike electricity rates. The public would then blame it for the rate hike. It’s fairly clear that the first part of that is correct. Slashing the budget of state-run Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) is a move intended to cause discontent with the DPP when electricity rates go up. Taipower’s debt, NT$422.9 billion (US$12.78 billion), is one of the numerous permanent crises created by the nation’s construction-industrial state and the developmentalist mentality it

Experts say that the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on Friday was likely the strongest to hit the country in decades, with disaster modeling suggesting thousands could be dead. Automatic assessments from the US Geological Survey (USGS) said the shallow 7.7-magnitude quake northwest of the central Myanmar city of Sagaing triggered a red alert for shaking-related fatalities and economic losses. “High casualties and extensive damage are probable and the disaster is likely widespread,” it said, locating the epicentre near the central Myanmar city of Mandalay, home to more than a million people. Myanmar’s ruling junta said on Saturday morning that the number killed had

Mother Nature gives and Mother Nature takes away. When it comes to scenic beauty, Hualien was dealt a winning hand. But one year ago today, a 7.2-magnitude earthquake wrecked the county’s number-one tourist attraction, Taroko Gorge in Taroko National Park. Then, in the second half of last year, two typhoons inflicted further damage and disruption. Not surprisingly, for Hualien’s tourist-focused businesses, the twelve months since the earthquake have been more than dismal. Among those who experienced a precipitous drop in customer count are Sofia Chiu (邱心怡) and Monica Lin (林宸伶), co-founders of Karenko Kitchen, which they describe as a space where they