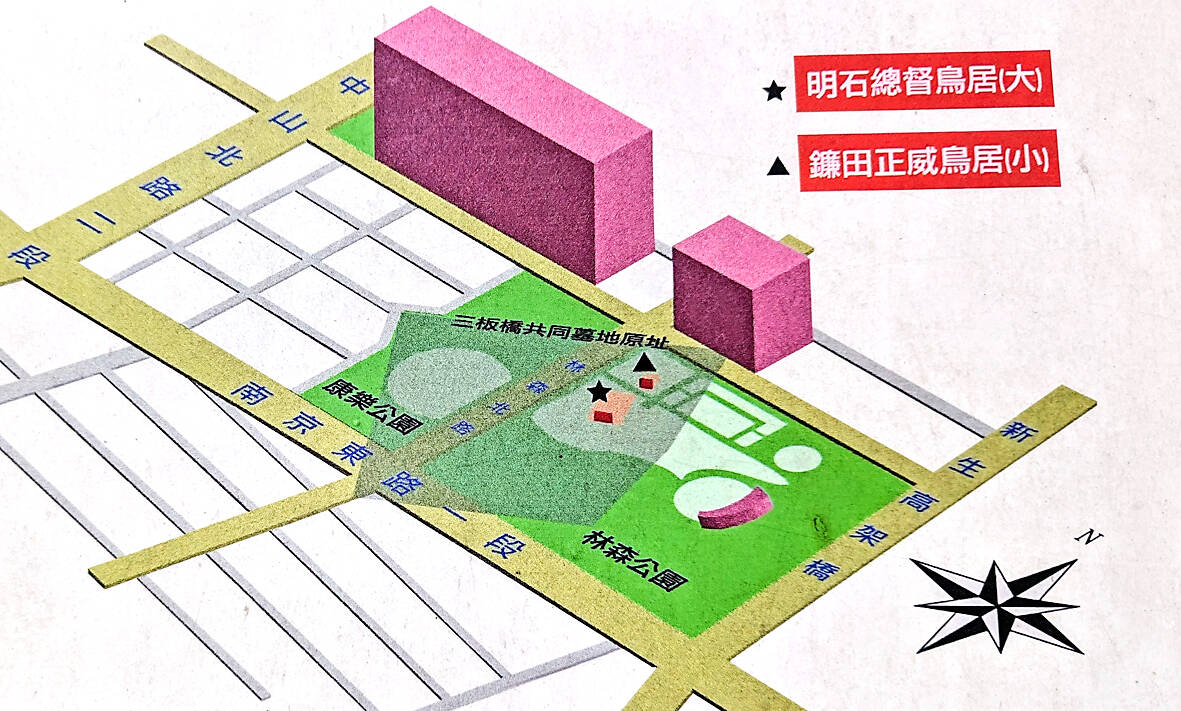

Oct. 21 to Oct. 27

Sanbanqiao Cemetery (三板橋) was once reserved for prominent Japanese residents of Taipei, including former governor-general Motojiro Akashi, who died in Japan in 1919 but requested to be buried in Taiwan.

Akashi may have reconsidered his decision if he had known that by the 1980s, his grave had been overrun by the city’s largest illegal settlement, which contained more than 1,000 households and a bustling market with around 170 stalls. Fans of Taiwan New Cinema would recognize the slum, as it was featured in several of director Wan Jen’s (萬仁) films about Taipei’s disadvantaged, including The Sandwich Man (兒子的大玩偶, 1983).

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

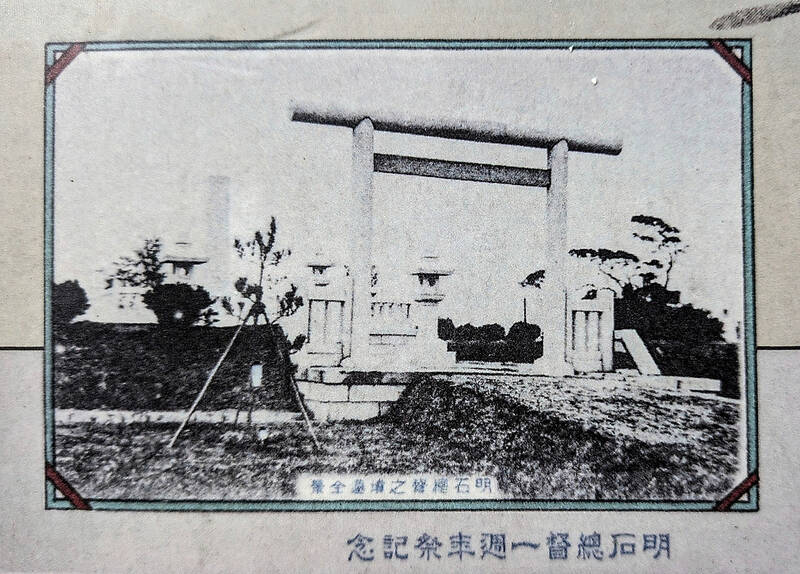

The residents used the gravestones as walkways and building material, and hung their laundry atop the two torii gates, which in Shintoism marks the boundary between the secular and sacred realms. The larger torii was erected for Akashi, while the smaller one was originally believed to have honored the mother of former governor-general Nogi Maresuke.

However, Nogi’s mother died in 1896 but the inscription on the torii gate notes that it wasn’t constructed until 1935, and old photos of the mother’s grave did not show the gate Today, a Bureau of Cultural Heritage entry states that it was built for Kamata Masatake, who served as Akashi’s secretary among other positions and died in Taipei in 1935. He was a fervent promoter of Shintoism.

The settlement was forcefully demolished in March 1997 under the insistence of then-Taipei mayor Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), despite strong local resistance. Only then did the gravestones and gates reemerge. The torii were temporarily moved to 228 Peace Memorial Park while the city built today’s Linsen Park (林森) and Kangle Park (康樂), but that was not yet the end of their strange odyssey.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

PRODUCTIVE RULER

Despite serving only 15 months, Akashi is considered one of the more productive governor-generals during 50 years of Japanese rule. Even though he died on Oct. 26, 1919 while visiting his hometown of Fukuoka, his body was shipped back to Taipei according to his last wishes. He is the only governor-general to be buried in Taiwan.

Akashi graduated from military school in 1889 and participated in the Japanese takeover of Taiwan that lasted from May to October 1895. He then became a prominent intelligence officer in Europe, and his activities contributed to the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

After Japan annexed Korea in 1910, Akashi headed the military police there before he was promoted to general and assigned to Taiwan in July 1918.

Taiwan’s energy demand was growing then due to the expansion of local industries, and Akashi organized the Taiwan Electric Power Co (Taipower’s predecessor) in 1919 and launched the Sun Moon Lake hydroelectricity project, which eventually displaced indigenous Thao settlements and nearly flooded their sacred Lalu Island (see “Taiwan in Time: A community that needed to ‘change,’” Oct. 18, 2018).

He also convinced the Japanese government to green light the costly Chianan Irrigation Canal (嘉南大圳), which was completed in 1930 (see “Taiwan in Time: The colonial water master,” May 5, 2019).

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Akashi promulgated the Taiwan Education Act, which established a formal schooling system for Taiwanese children, with options for secondary education as well as vocational and teacher training. The goal was to accelerate assimilation, but it opened up many more educational opportunities for regular Taiwanese, even though the system still favored Japanese students, writes Cheng Cheng-cheng (鄭正誠) in “Taiwan Governor-General Motojiro Akashi’s inspection of the east coast and his illness” (台灣總督明石元二郎的東台灣巡視與罹病初探).

In addition, he re-established the high court, which was abolished in 1898, and removed the governor-general’s ability to suspend judges.

BURIED IN SANBANQIAO

Akashi traveled extensively in Taiwan, making inspections to different locales almost every month. Just two days after returning from a 51-day trip to Japan to set up the power company, he set out on a one-month journey to the east coast on May 29, 1919. He fell ill afterward and although he recovered, his health was never the same.

In August, Akashi helped establish the Taiwan Army commander position to take over military duties from future governor-generals; this commander would directly answer to the emperor. He then requested to abolish the rule that Taiwan could only be governed by military officers; his successor Kenjiro Den was the colony’s first civilian governor-general.

In October, Akashi headed home to recuperate and died before he could return to Taiwan. Just three days after his death, his body was placed on a ship and arrived in Keelung on Nov. 1. A stately ceremony was conducted at Sanbanqiao Cemetery.

Due to its proximity to the formerly walled city of Taipei, where the Japanese set up their administrative headquarters, the cemetery had developed into a prime resting place for the Japanese elite. The first notable figure to be buried there was Nogi’s mother, and after Nogi and his wife committed suicide in 1912, locks of their hair were brought to Taiwan and placed in the mother’s grave. All remains have since been moved to Japan.

Sanbanqiao also contained the main crematorium for Taipei. This was open to all residents, and noted democracy activist Chiang Wei-shui (蔣渭水) was cremated there after his death in 1931.

FROM SLUM TO PARK

The illegal settlement atop the cemetery was first set up by refugees from China’s Zhoushan Islands and Hainan Island, and later they were joined by job-seekers from the south of Taiwan, writes Tsai Chin-tang (蔡錦堂) in “From Sanbanqiao Japanese cemetery to Linsen and Kangle Parks” (從三板橋日人墓園到林森康樂公園文).

The original funeral hall was converted into a high-end private mortuary that operated until the 1970s; today the Changan Pumping Station stands in its place.

The city had long wanted to do away with the settlement as it was surrounded by prime real estate, but no mayor wanted to deal with it until Chen. The residents were not happy with the compensation, and pushed back with the support of scholars, politicians and students.

After the settlement was razed, Akashi’s remains were moved to Fuyinshan Christian Cemetery (福音山) in New Taipei City’s Sanchih District (三芝), but the headstone was abandoned at the construction site for the future Neihu MRT station. Around 2005, antique collector Kuo Shuang-fu (郭雙富) had it dug up and donated it to the Taiwan Historica Library in Taichung, where it remains, albeit fractured into several pieces. The other Japanese remains are now interred at Taichung’s Paochueh Buddhist Temple (寶覺寺).

The parks were completed in 2003, but the torii gate was left in 228 Peace Memorial Park. A 2009 Liberty Times (Taipei Times’ sister paper) article details how the city “forgot” about the gates and left them in bad shape with an information display that was full of errors.

After much effort, in 2011, the two gates were returned to their original location in Linsen Park.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has