In the tourism desert that is most of Changhua County, at least one place stands out as a remarkable exception: one of Taiwan’s earliest Han Chinese settlements, Lukang. Packed with temples and restored buildings showcasing different eras in Taiwan’s settlement history, the downtown area is best explored on foot. As you make your way through winding narrow alleys where even Taiwanese scooters seldom pass, you are sure to come across surprise after surprise.

The old Taisugar railway station is a good jumping-off point for a walking tour of downtown Lukang. Though the interior is not open to the public, the exterior is remarkably well maintained and — along with the abandoned sugarcane locomotive nearby — serves as a reminder of the Japanese industrialization of Taiwan. For anyone who comes to Lukang by car, there is also a large parking lot here. If you’re using public transit, there is a bus stop right in front of the station.

What follows is a suggested route for a leisurely 3.5km afternoon walk. You can follow along with the online map, but there’s no need to stick strictly to this route. Part of the fun of such a walk is in exploring unknown alleys, and going wherever your ears, eyes, and nose lead you. There are surely many important places missing from this itinerary, but such is the nature of trying to draw a single line through a city so packed with interesting sights.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

TRADITIONAL ARCHITECTURE

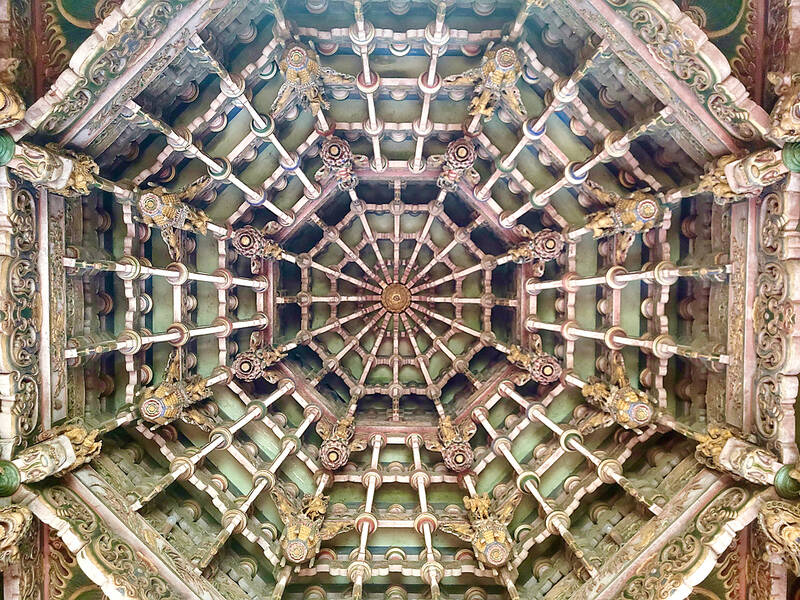

From the Taisugar railway station, head to Sanmin Road (三民路) and then west to the beautiful Longshan Temple complex (鹿港龍山寺). To step into the first courtyard is to step out of the chaos of the modern world and into a more serene, orderly space that harkens back to the early days of Han settlement in Lukang. In fact, a temple has stood here since 1786, though the current structures are the end result of no fewer than five major reconstructions or renovations, four of which were carried out after earthquake damage.

The centuries-old banyan trees and pleasingly symmetrical facades and roofs with their classic flying eaves and dragon decorations certainly make the Longshan Temple worth a visit, as do the intricate wooden carvings in the porticos and smoke-tinted door god paintings. However, the highlight of the visit — at least for a non-believer — may be the meditative garden at the very back. Koi swim under a bridge spanning a pond flanked by two brick buildings, as turtles sun themselves on little islands in the pond, all set against the backdrop of a waterfall and artfully manicured trees.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Leave the temple via the alley to the north of the entrance plaza and make your way north and east, following the red brick pavement. Just before reaching Jhongshan Road (中山路), you will pass the Yilou building (鹿港意樓), a photogenic 200-year-old home purchased and restored with private funds. Take note of the gorgeous star fruit tree poking its head over the brick wall near the back: legend has it, this was planted by a man as a reminder of himself for his wife, just before he headed out on business, only to never return.

A MAZE OF ALLEYS

By now, you’ll have reached Jhongshan Road. Look for the Ting Family Historical Residence (鹿港丁家古厝), numbers 130, 132 and 134 on the opposite side of the road. The Tings were successful merchants in 19th century Lukang and this building has been renovated and opened to businesses and the general public. After walking through the shops, walk further in to reach the gorgeous courtyards, painted in subdued reds and blues and accented by painted reliefs.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

Continuing out the back of the Ting Family Residence puts you right at the entrance to the Lukang Folk Arts Museum, an absolute must-see, if only from the gate. The immaculate building and grounds are one of the best examples of colonial-era architecture in the country. Whereas many of the so-called “Western mansions” built by wealthy families of the early 20th century now lie in a semi-ruined state, this one looks as if construction was just finished last year. If you have the time, spend an hour walking the grounds and exploring the museum exhibits inside, which present a succinct yet rich overview of the cultural heritage of Lukang’s Han settlers.

Next, continue weaving your way counterclockwise around the museum grounds through more scenic alleys (and dead ends), making your way back to Jhongshan Road and the Ting residence’s front entrance. Cross the road onto Sinsheng Street (新盛街) and take the first right turn back onto the familiar red-brick pavement. This winding lane, Jiuqu Lane (“Nine Turns Lane” 九曲巷), passes by an interesting array of homes of varying degrees of modernity and decay.

The brick pavement ends at Liulutou (“where six roads start” 六路頭). I was unable to find a sixth road, but there are certainly still five roads that come together at this point, including the old ox cart trail leaving the city for southern Changhua (look for the brick archway with a blue top). Follow the old ox cart trail for a while if you like, then make your way north to Daming Road (大明路) and turn right to reach a bunch of restaurants and food vendors.

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

FOOD AND CROWDS

This would be a great place to sample one of Taiwan’s local dishes, the meatball dumpling (肉圓), which originated in Changhua. If you’re not yet hungry, don’t worry; there will be plenty more food stalls to come very soon. Follow Daming Road to its end and turn left at the Family Mart onto yet another alley paved in red brick. Just a minute up the road on the left, there is a modern curiosity: a long row of red torii gates set in an empty lot between two buildings leading toward a tiny Shinto shrine. Right next door is yet another beautifully restored property combining traditional Fujianese and Western elements in its architecture, the Heci Villa (鹿港鶴棲別墅). This once served as both a residence and a business headquarters, but nowadays serves as an art gallery.

Once you get to the next major intersection, turn left onto Minquan Road (民權路), and walk to the next red brick alley on your right — the one with hundreds of people in it. This is Lukang’s “Old Street” where you can buy souvenirs, or fill up on local delicacies and standard night market food. After eating your way down the street, turn right and then left to reach Lukang’s most famous temple and the end of the walking tour: the Lukang Mazu Temple (鹿港天后宮).

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

The temple is one of the oldest and most important sites of Mazu worship in Taiwan, and its present site will be 400 years old next year. Just as ornate as Longshan Temple at the beginning of the walk, the Mazu Temple is, however, much less serene. It lacks the manicured garden and is much louder, both visually and aurally. A large number of worshippers visit every day, and it’s normal to see throngs of people milling about the entrance after worship, grabbing a bite from one of the food vendors nearby. If you’re looking for a bustling temple atmosphere, this is the place.

Leaving the crowds behind, make your way north and east toward the Lukang Stadium. On the east side of the stadium is a bus stop with the most convenient connections back to Changhua train station, or back to your car at the Taisugar railway station.

PUBLIC TRANSIT

Photo: Tyler Cottenie

From Taichung High Speed Rail: Take Bus 6936A to the Fusing Township Farmers Association stop and walk a few minutes to the Taiwan Sugar Train Station. Return by Bus 6933 from the Lugang Township Office stop.

From the Changhua railway station: Take Bus 6900, 6933 or 6934 to the Taiwan Sugar Train Station stop. Return by Bus 6901 from Lukang Station stop next to the stadium or Bus 6902 from the Theater stop (last return bus around 5pm). For a later return, take Bus 6933 mentioned above toward Taichung HSR around 8pm, but get off at the Changhua train station.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,