Though some now point to a new rivalry between China and the US in southeast Asia, there are no easy equivalences to the Cold War, when the region’s governments were forced to declare for one side or the other. While Beijing has actively propped up several of the region’s dictators and junta regimes and exerted huge if diverse influence, one could also say this growing economic integration with China is just following the pattern of Latin America, whose economies fell into orbit around the dominant economy of their own region, the US.

“Is China the celestial kingdom of the past, seeking to reassert its former tributary relations with Southeast Asia?” asks Enze Han, a scholar at the University of Hong Kong in his new book The Ripple Effect: China’s Complex Presence in Southeast Asia. Or, “is Beijing primarily interested in economic development,” and “will contemporary China embody something entirely different?”

To find an answer, Han looks at diverse phenomena from live beef smuggling out of Myanmar, Chinese-run casino cities throughout continental southeast Asia and plans for a high speed rail network from Beijing to Singapore. In doing so, he finds that China’s newfound influence comes at every level from Beijing’s “wolf warrior” diplomats down to private Chinese entrepreneurs who run banana plantations in Laos and Chinese tourists, who before COVID-19 accounted for a huge chunk of the visitors — between 12 and 36 percent of arrivals — in the 10 member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Simply put, China’s influence is massive, but there is no master plan. China certainly has political agendas at play, but not always. Often the growing relationship is just about the bottom line, and even when these new relationships produce big, ugly problems like environmental devastation, human trafficking and markets crashed by the whims of China’s fickle economy, there is not always a central authority or force to blame.

Whether good or bad, this integration is happening — and at a frightening pace. Within the past decade, China has become not only the largest importer to ASEAN, but also the biggest buyer of their exports as well, absorbing US$500 billion in ASEAN-produced goods in 2021, more than from the US, EU and Japan combined.

In the process, China has come to dominate regional agricultural markets to the point that many Thais have been unable to afford their own homegrown durians and huge swaths of rice paddies from Myanmar to Vietnam have been replanted with corn to feed cows that end up in Chinese hot pot. China’s sudden border closings during COVID-19 sent several such produce markets crashing.

One of the region’s most symbolic and high profile China-driven projects is that of the pan-Asian railway, a European colonial dream revived by China in 2007 when it entered into partnerships with Laos, Thailand and Malaysia for a high speed rail network from Kunming to Singapore. A section from Kunming through Laos has been operating since 2021, and construction is now underway to extend this line to Bangkok by 2026, while a third leg through Malaysia is set for completion by 2027.

Manufacturing integration has come through China-built Special Economic Zones (SEZs) in Indonesia, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Malaysia. These have facilitated legitimate supply chain integration between Chinese companies and their southern neighbors, including a regional logistics hub for Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba in Thailand.

But the SEZs have also allowed Chinese businesses to hedge against western decoupling, anti-dumping measures and sanctions. Bad practices have included “cotton laundering,” whereby cotton from Xinjiang’s forced labor factories is exported to a third country — say, Vietnam — then woven into clothes bound for the US or Europe, where Xinjiang cotton is banned.

‘FRAGMENTED AUTHORITARIANISM’

Han invokes the notion of “fragmented authoritarianism” to describe this multi-track influence, by which the advance of Chinese capital is not “uniformly coordinated from a central authority, but rather driven and implemented by regional and local interests, such as state-owned, private and hybrid companies.”

The general picture is of China spreading over the region like a fine mist, though there are also direct political vectors. The “China model,” defined here as “the duality of economic freedom and absolute political control” has cast an authoritarian shadow across southeast Asia, where dictatorships and juntas now outnumber democracies. In Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia, China has actively fostered dictators and party-states through exports of both weapons and technologies for facial recognition and Internet censorship.

China has also shielded the crimes of these military regimes. For Myanmar, China has actively blocked or altered at least three UN Security Council resolutions, including condemnation of the 2017 Rohingya genocide and the 2021 overthrow of the nation’s democratically elected leader Aung San Suu Kyi.

But it has also been argued that China’s diplomatic “successes” have at least resulted from the West’s diplomatic failures. Not only Han, but also American analyst Benjamin Zawacki and Swedish author Bertil Linter, have noted a pattern by which the West has been caught in a catch-22 by anti-democratic political takeovers — like that in Myanmar in 2021, or Thailand in 2006 and 2014 or Cambodia in 2016. Unable to turn a blind eye to the erosion of civil liberties, human rights and democracy, the West reacted to these coups with sanctions and diplomatic disengagement. China, meanwhile, has opportunistically stepped into the vacuum with aid and investment.

In Cambodia, for example, following ruler Hun Sen’s dismantling of a shared-power government in 2016, China became Cambodia’s largest aid donor and in 2017 financed almost 70 percent of the nation’s new roads and bridges. In 2021, Hun Sen declared, “If I don’t rely on China, who will I rely on? If I don’t ask China, who am I to ask?”

CRIMINAL ENTERPRISES

But China’s official ties with weak southeast Asian states has also opened the way for unofficial criminal enterprises. Chinese gangsters have built casino cities, some now home to 100,000 or more people, in Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam and online gambling centers in the Philippines.

Several of the most notorious casino cities, which are generally run without interference from local law enforcement, have also been linked to money laundering, drugs and cyber scams centers staffed by tens of thousands of victims of kidnap or human trafficking. The scam gangs operate by a truly abhorrent system, and while Chinese authorities have undertaken extraordinary renditions to bring plane loads of these criminals back to China for trial, it’s also emerging that some may have vague but direct relationships to the Chinese government.

Since publication of The Ripple Effect, Chinese convicted felon She Zhijian, developer of Myanmar’s infamous Schwe Kokko casino city, has given interviews from jail in Thailand claiming that he was in fact a spy working for China’s Ministry of State Security, though no other sources have yet confirmed this. While developing Schwe Kokko, he also claimed the area was an SEZ under the banner of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, something Chinese authorities later denied. Though the truth of She’s claims may never be known, his case shows the incredible fuzziness of the line between China’s private actors and Beijing government policy.

In The Ripple Effect, Han does well in presenting the unbelievable scale, variety and pace of China’s multitrack advance into southeast Asia. But this slim volume, just 157 pages before the footnotes, is mostly a summary of major (if often overlooked) trends and offers few big conclusions. On certain issues — like capital flight from Hong Kong to Singapore, or in saying that Confucius Institute language centers seem “harmless enough” — it also feels as if Han, a Hong Kong-based academic, may be hamstrung by fears of violating Hong Kong’s new Security Law, which forbids criticism of Beijing.

Yet Han’s major contribution is the very valid point that China’s massive economic and cultural penetration into southeast Asia is about more than just the monolithic government in Beijing. It adds a new complex layer onto the region, which now must navigate a new and shifting balance between East and West.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

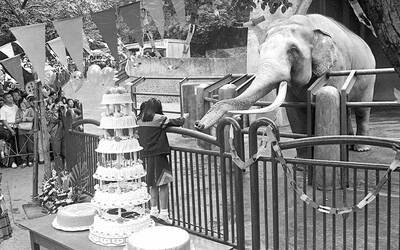

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

Mother Nature gives and Mother Nature takes away. When it comes to scenic beauty, Hualien was dealt a winning hand. But one year ago today, a 7.2-magnitude earthquake wrecked the county’s number-one tourist attraction, Taroko Gorge in Taroko National Park. Then, in the second half of last year, two typhoons inflicted further damage and disruption. Not surprisingly, for Hualien’s tourist-focused businesses, the twelve months since the earthquake have been more than dismal. Among those who experienced a precipitous drop in customer count are Sofia Chiu (邱心怡) and Monica Lin (林宸伶), co-founders of Karenko Kitchen, which they describe as a space where they