Oct. 7 to Oct. 13

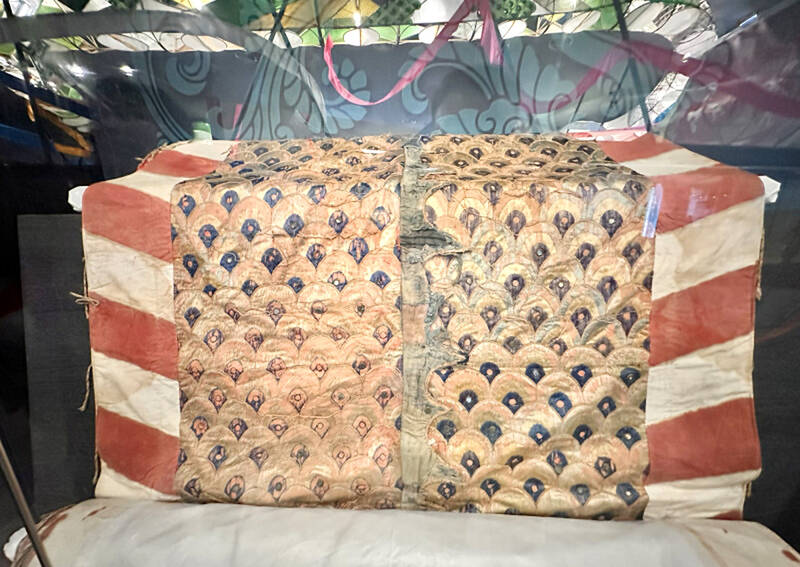

The Great Dragon Flags were so lavish and intricate that it’s said to have exhausted the supplies of three embroidery shops. Others say that the material cost was so high that three shops quit during production and it was finished by a fourth. Using threads with pure gold, the final price to create the twin banners was enough to buy three houses in the 1920s.

Weighing 30kg each and measuring 454cm by 535cm by 673cm, the triangular flags were the pride of the Flying Dragons (飛龍團), a dragon dance troupe that performed for Chaotian Temple (朝天宮) in Yunlin County’s Beigang Township (北港). The three-centuries old shrine is dedicated to the sea goddess Matsu, and the flag’s border is adorned with various aquatic creatures such as clams, frogs, shrimp and fish.

Photo: Chen Tsan-kun, Taipei Times

What’s more impressive is that the flags use 26 out of 30 recognized traditional Taiwanese embroidery techniques. Its Bureau of Cultural Heritage entry states that it’s the largest embroidered flag in Taiwan and contains the most gold and cotton. The gold embossing of the images also rises higher than any other flag found so far.

The banners were first featured in the press in 1929, and were last seen being used during a procession in the 1950s. Troupe member Wu Teng-hsing (吳登興) only recalls seeing them as a child, and noted that the huge flags were cumbersome, often getting entangled in electric poles.

Wu and other members found the flags in a chest at troupe headquarters around 2012. After they were certified as cultural relics, both were sent to the National Center for Research and Preservation of Cultural Properties for restoration.

Photo: Hung Jui-chin, Taipei Times

Work was completed on one of the flags in 2021, and along with other artifacts from the troupe, it is now on display at the Beigang Cultural Center through Nov. 30. This includes the “dragon skin” costume, which at 20.4 meters is the longest embroidered cultural relic in Taiwan.

WORSHIP CENTER

According to legend, in 1694 a monk named Shu-pi (樹璧) arrived in Beigang (then named Bengang, 笨港) with an effigy of Matsu from Tianhou Temple in Meizhou (湄洲), China, where Matsu lived before she became a deity. Shu-pi allegedly landed on the 19th day of the third lunar month — four days before Matsu’s birthday — and placed the effigy down to wash his hands in a well. When he tried to pick it up again, he found that he was unable to lift it. Locals saw it as a sign and began to worship it.

Photo courtesy of Yunlin County Department of Culture and Tourism

A small thatched shrine was built around the effigy around 1700, but as its popularity grew, locals pitched in to expand and upgrade the structure during the ensuing three centuries. After a successful campaign against pirates in 1839, general Wang Te-lu (王得祿) gifted a massive bell to the Chaotian Temple to thank Matsu for her protection during the sea battle. He also reported this to the Qing emperor in Beijing, who bestowed a plaque and honors upon the temple.

The temple was seriously damaged in the 1905 Chiayi Earthquake, but it was rebuilt in 1911. The final touches were added in 1968 and 1970, which included constructing a new drum tower and nearly doubling the height of the main hall.

Chaotian Temple established itself as the center of Matsu worship in Taiwan during the mid-1800s, attracting scores of pilgrims from all across Taiwan, particularly during its two annual processions — one held during Lantern Festival and the other on the 19th day of the third lunar month to commemorate Shu-pi’s arrival.

Photo courtesy of China Educational and Cultural Exchange Association

The Lantern Festival procession wasn’t launched until 1912, but it became the main event until the 1930s, when the latter was elevated under government orders, writes Tsai Yu-hua (蔡侑樺) in “Changes in Chaotian Temple’s Matsu procession during the Japanese era” 日治時期北港朝天宮媽祖繞境活動之變遷). Today, the procession on the 19th and 20th of the third lunar month remains the primary event.

SURGE IN POPULARITY

Religious activities were put on hold after the Japanese colonizers arrived in 1895, as the area was rife with unrest due to local resistance. But in 1897, a Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) reported scores of pilgrims heading to the temple to offer incense.

Photo courtesy of Lee Wen-te, Taipei Times

The Japanese tolerated local religion at first. In fact, officials often attended temple events to strengthen their image among the masses. Governor-general Samata Sakuma, for example, visited Beigang in 1913 and gifted a plaque to Chaotian Temple through a traditional ceremony. Like the emperor’s plaque, it was a symbol of authority, but it also showed official support of the temple.

The establishment of the private sugar railroads (see “Taiwan in Time: The sugar express,” Sept. 8, 2024) made it easier for people to visit Beigang. The town was accessible through three separately-owned rail lines.

Starting in 1913, the sugar rail operators began competing for passengers heading to the processions, with two of the lines slashing their prices by 50 percent during the Lantern Festival event. They even sent salespeople to various towns to persuade residents to choose their line. It was a lucrative boost to their business, as more than 30,000 pilgrims visited the temple per day during the festivities. Countless temples also made their way to Beigang with thousands of patrons in tow.

A notable patron was Dajia’s Jenn Lann Temple (鎮瀾宮), whose famous annual pilgrimage originally concluded at Chaotian Temple. However, due to a dispute in 1988, the two temples cut ties and Jenn Lann changed its destination to Fengtian Temple (奉天宮) in Chiayi. The notable Baishatun (白沙屯) Matsu procession still concludes at Chaotian Temple.

With so many outside troupes visiting — the 1936 Lantern Festival event featured more than 80 — a strong local presence was needed, leading to the proliferation of Beigang performing groups, writes Wang Chi-hsu (王志旭) in “Beigang’s traditional religious organizations and modern nonprofit organizations” (北港的傳統信仰組織與現代社團).

DRAGON DANCING

The number of local troupes has dropped in recent decades, but the Flying Dragons, established as early as 1924, continue to operate. At that time, it was the only dragon dance troupe on Chaotian Temple’s procession roster, Tsai writes. The group was led by Weng San-lian (翁三連), who arrived in Taipei from Fuzhou, China in 1919. He moved to Beigang in August 1920, presumably to train locals in dragon dancing, which had only become part of the festivities after 1912 due to the art form’s association with Lantern Festival.

Most Flying Dragons were ordinary shopkeepers, laborers and farmers. The only wealthy members on the founding roster were merchants Huang Chu-ken (黃竹根) and Liu Huo-tan (劉火炭), whom Tsai surmises funded the group’s activities.

Records show that the group purchased significant amounts of calcium carbide to use as lighting effects during night performances. In 1922, a large tin incense burner was forged for the Flying Dragons, cementing their status as an organized troupe, Tsai writes.

Work on the Great Dragon Flags and dragon skin began around 1926. During this time, other troupes also shelled out to create impressive banners and equipment, indicating Beigang’s prosperity and the temple’s popularity. Numerous private and public projects were also carried out during this period until the Great Depression tempered things in the early 1930s.

The Japanese began clamping down on temples during the 1920s, but local processions mostly continued. The authorities kept shortening the festivities during the 1930s, and in 1935 they moved Chaotian Temple’s main procession to the 19th day of the third lunar month on grounds that it was too cold during Lantern Festival. In 1938, this procession, which could originally last for days, was cut to one day, and after that it was likely canceled due to World War II.

The procession continues to go strong today — this year’s event produced a record 162 tonnes of firecracker ash, and also saw a record number of participating troupes.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern