If Elon Musk is a name that sounds as if it was invented by Ian Fleming, there’s more than a hint of the Bond villain about the South Africa-born American billionaire. It’s not just the extraordinary wealth, which hovers around the quarter of a trillion dollars mark, but the SpaceX business that sends rockets into space and seeks Martian colonization (very Hugo Drax and Moonraker) and the hypersensitive ego.

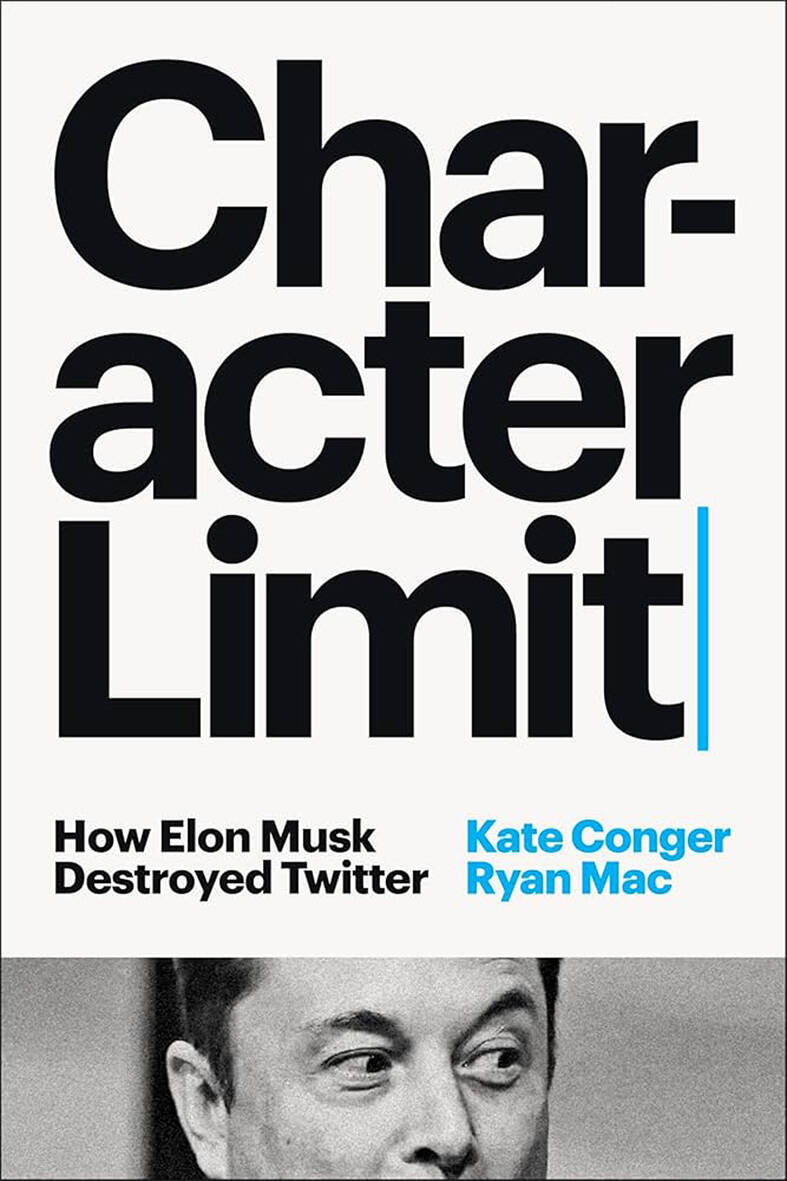

All of these sides of Musk are on painful display in Kate Conger and Ryan Mac’s book Character Limit: How Elon Musk Destroyed Twitter. So unappealing is the portrait this pair of New York Times technology reporters paint that a more fitting title might be Character Assassination. Or it would if it wasn’t for the fact that Musk himself provides most of ammunition discharged in this damning account.

As the subtitle suggests, the book focuses on Musk’s controversial acquisition of the social media platform Twitter, now renamed X, which the authors describe as “a new, harsher and much more cynical social media company.”

It seemed an unlikely development for someone who became the richest person in the world through building extraterrestrial rockets and electric cars, but Musk started out as an Internet entrepreneur making his first fortune with an online city guides business, before becoming even more filthy rich from the sale of his share in PayPal.

He was also a Twitter addict, one of those people who couldn’t let a day pass — and often an hour — without posting his opinion or reposting someone else’s. In a previous era the gilded classes liked to demonstrate their affluence and influence with the ownership of newspapers. But as early as 1998 Musk had seen the writing on the screen.

“I think the Internet,” he declared back then, “is the be-all and end-all of media.”

Although Twitter wasn’t the be-all and end-all of anything other than cultural warfare, by the end of the last decade it was established as a vital resource for tens of millions around the globe, and the company aspired to rival Facebook. Its chief executive was Jack Dorsey, a curious hippy-billionaire given to gnomic statements, who tried to navigate a path for the platform between the jagged rocks of libertarian principle and liberal concern. It wasn’t an entirely successful strategy, and a divided board eventually encouraged his exit.

His successor, Parag Agrawal, was a devoted technocrat who seemed to believe that all solutions to the toxic social conflicts associated with the platform could be found in better coding. But he never really got a chance to make his mark because he was immediately shown the door when Musk bought the company for US$44 billion just over two years ago. Or rather he was legally compelled to buy it after making an inflated offer from which, despite his best efforts, he was unable to back out. The court case that clarified Musk’s obligation also revealed a cache of text messages the billionaire sent relating to the acquisition. They show a rash, impatient character given to bouts of intimidation, grandstanding, depression and megalomania.

He practically forced Twitter to sell to him without any due process, and then complained long and hard that he hadn’t had the opportunity to assess the company’s true worth. Nor did he have any kind of coherent plan about where to take the business. He loathed its advertising model, and set about alienating the companies that provided most of Twitter’s income, yet his alternative — raising money through a verification system — was ill-conceived and counterproductive.

The more revenue declined, the more he stripped the workforce, thus losing expertise that in turn stymied efforts to reform the business. As he tweeted six months after the purchase: “How do you make a small fortune in social media? Start out with a large one.”

The justifying cause to which he lays claim is free speech, a noble concept that tends to splinter on impact with complex reality.

While the authors may be a touch too inclined to see any questioning of liberal shibboleths as tantamount to hate speech, there’s little doubt that if Twitter always had its nasty elements it has become a larger cesspool, if smaller business, under Musk.

Throughout it all, with only minor exceptions, he carries on tweeting — or what are we supposed to call it now, X-ing? According to the authors, he became obsessed with becoming the most followed contributor on his own platform, launching a frenzied investigation when the numbers began tailing off, convinced that disgruntled members of the old regime had thrown a digital spanner in the works.

At one point, when a tweet he makes supporting one Super Bowl team gets less attention than President Biden’s backing of the same team, he walks out of the event and flies to San Francisco to oversee efforts to find out how this presidential scene-stealing had been allowed to happen.

There is growing evidence to suggest that social media is deleterious to mental health, and nothing in this book leads the reader to believe otherwise. The kind of polarized and insular thinking that algorithms on platforms such as Twitter/X are primed to spread is in a way personified by Musk, who has persuaded himself that he is on a crusade to save America and the world from what he calls the “woke mind virus.”

It’s not as if there aren’t troubling aspects to some of the more self-righteous social justice movements, but Musk has climbed into bed with Donald Trump, both men citing popular support while being chiefly focused on self-enrichment and the gratification of their overweening vanity.

By the end of this book, you can’t help but feel that Mars may well be the right place for this strange and obscenely wealthy character.

Last week saw the appearance of another odious screed full of lies from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) Ambassador to Australia, Xiao Qian (肖千), in the Financial Review, a major Australian paper. Xiao’s piece was presented without challenge or caveat. His “Seven truths on why Taiwan always will be China’s” presented a “greatest hits” of the litany of PRC falsehoods. This includes: Taiwan’s indigenous peoples were descended from the people of China 30,000 years ago; a “Chinese” imperial government administrated Taiwan in the 14th century; Koxinga, also known as Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功), “recovered” Taiwan for China; the Qing owned

When 17-year-old Lin Shih (林石) crossed the Taiwan Strait in 1746 with a group of settlers, he could hardly have known the magnitude of wealth and influence his family would later amass on the island, or that one day tourists would be walking through the home of his descendants in central Taiwan. He might also have been surprised to see the family home located in Wufeng District (霧峰) of Taichung, as Lin initially settled further north in what is now Dali District (大里). However, after the Qing executed him for his alleged participation in the Lin Shuang-Wen Rebellion (林爽文事件), his grandsons were

I am kneeling quite awkwardly on a cushion in a yoga studio in London’s Shoreditch on an unseasonably chilly Wednesday and wondering when exactly will be the optimum time to rearrange my legs. I have an ice-cold mango and passion fruit kombucha beside me and an agonising case of pins and needles. The solution to pins and needles, I learned a few years ago, is to directly confront the agony: pull your legs out from underneath you, bend your toes up as high as they can reach, and yes, it will hurt far more initially, but then the pain subsides.

A jumbo operation is moving 20 elephants across the breadth of India to the mammoth private zoo set up by the son of Asia’s richest man, adjoining a sprawling oil refinery. The elephants have been “freed from the exploitative logging industry,” according to the Vantara Animal Rescue Centre, run by Anant Ambani, son of the billionaire head of Reliance Industries Mukesh Ambani, a close ally of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The sheer scale of the self-declared “world’s biggest wild animal rescue center” has raised eyebrows — including more than 50 bears, 160 tigers, 200 lions, 250 leopards and 900 crocodiles, according to