Sept. 30 to Oct. 6

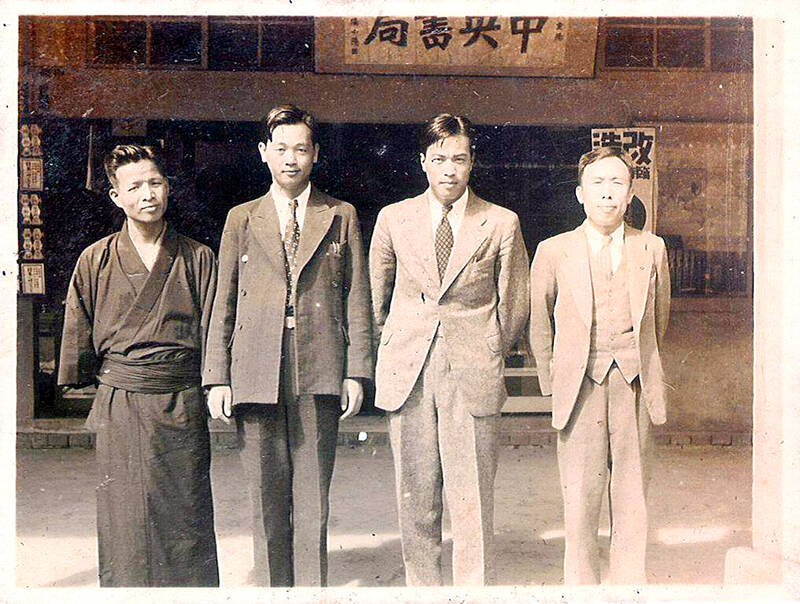

Chang Hsing-hsien (張星賢) had reached a breaking point after a lifetime of discrimination under Japanese rule. The talented track athlete had just been turned down for Team Japan to compete at the 1930 Far Eastern Championship Games despite a stellar performance at the tryouts. Instead, he found himself working long hours at Taiwan’s Railway Department for less pay than the Japanese employees, leaving him with little time and money to train.

“My fighting spirit finally exploded,” Chang writes in his memoir, My Life in Sports (我的體育生活). “I vowed then to defeat all the Japanese in Taiwan and represent Japan at the Olympics!”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Two years later, Chang did just that, becoming the first Taiwanese athlete to compete in the 1932 games in Los Angeles, officially listed in the Olympic records as Cho Seiken Although he didn’t make it past the preliminaries, it was vindication for him as the only Taiwanese on the 36-member team. He also competed in the 1936 games.

However, few in Taiwan were aware of Chang’s accomplishments before the 2000s, writes National Taiwan Normal University professor Lin Mei-chun (林玫君) in the foreword to Chang’s memoir.

Chang was glad to finally be free of colonial rule and become a true “Chinese” after World War II. But the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was not exactly kind to Taiwan’s former Japanese subjects — Chang’s cousin Chang Hsing-chien (張星健) was even one of the many victims of the White Terror.

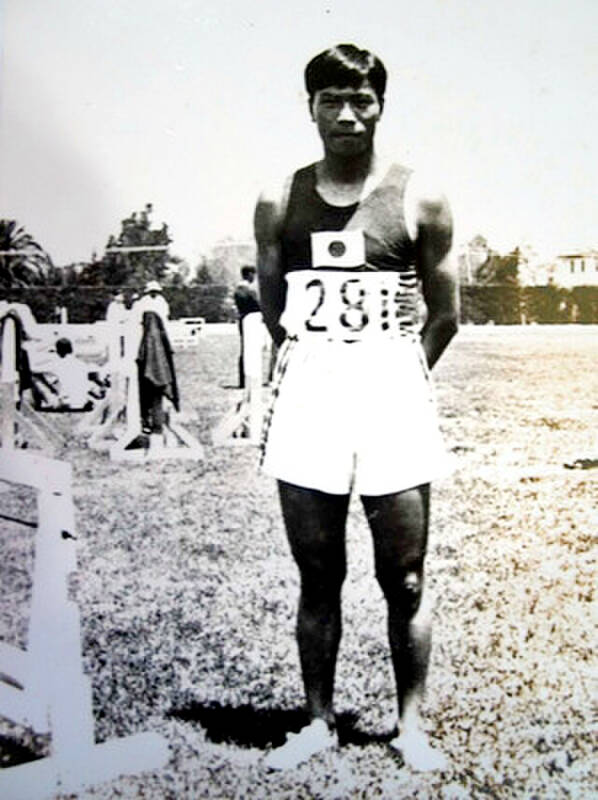

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chang was pretty much erased from history since he represented Japan; instead both China and Taiwan celebrated Chinese sprinter Liu Changchun (劉長春), who also participated in the 1932 and 1936 games, as the first national Olympian.

Despite Chang’s dedication to the nation’s post-war sports scene and abundant international experience, he never attended another Olympics as a trainer or coach — although he admits that he was “bad at public relations and politics.”

His frustration was clear in the following passage: “Late president Chiang [Kai-shek (蔣中正)] stressed that no matter our past and present, no matter our nationality, as long as we’re ethnic Chinese, we’ll always belong to the Chinese nation … But 30 years later, I’m still forced to endure this feeling of being a foster son.”

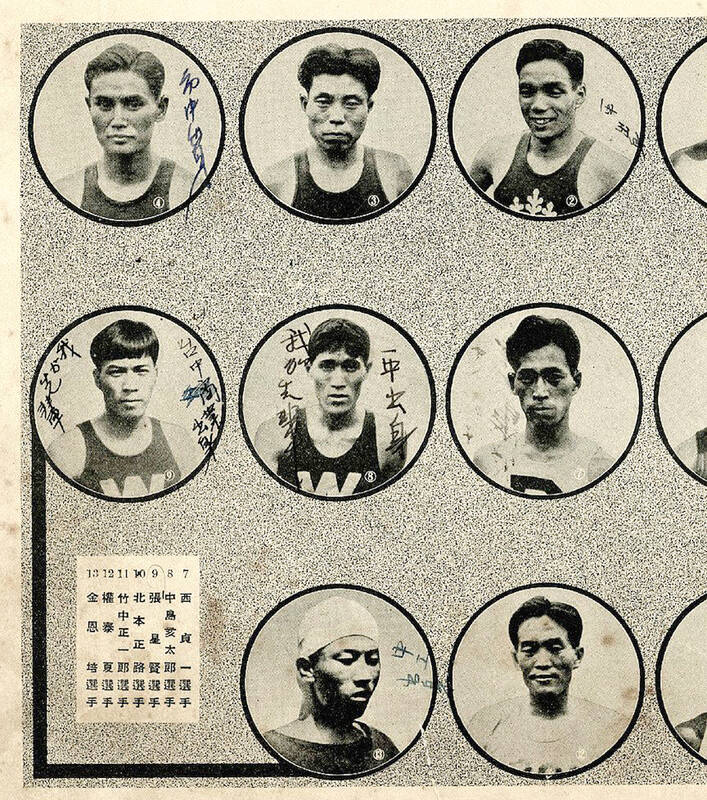

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

PROMISING ATHLETE

Born in Taichung’s Longjing District (龍井) on Oct. 2, 1910, Chang loved sports from a young age.

“It was about a 20-minute walk from my home to school, and everyday I jogged or even ran the entire way before and after class. Whenever there was a sports meet or tournament, I would find a way to attend,” he writes.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

After enrolling in the Taichung School of Commerce in 1925, he played a number of sports but settled on track and field after finishing second in the school marathon.

His first official competition was a long distance run from Taichung to Changhua, finishing eighth out of 150 and qualifying him for the next round between Fengyuan and Taichung. He finished second, and was chosen as one of 10 athletes to represent Taichung in the national race. Chang did not do well because he was too nervous, he recalls.

Later that year, he registered for a national meet in Taipei with no intent on winning; he just wanted the experience. He first competed in the 1,500m run, but because he hadn’t slept the night before he put in a poor performance and ended up vomiting out of exhaustion. After a few hours of rest, he headed to the triple jump.

That day, the favored candidate was unexpectedly disqualified, and Chang performed beyond his usual distance, winning his first ever gold medal.

“This was the match that decided my fate,” he writes.

In 1929, Chang set the Japanese record for farthest triple jump by a secondary school student during an island-wide meet. This qualified him to represent Taiwan at the Meiji Shrine Games in Tokyo, which featured athletes from all over Japan, including its colonies. Although Chang didn’t fare too well, it proved that he could compete on a national level and not just in Taiwan.

TAIWANESE PRIDE

Chang’s life was not ideal after graduation. With the recommendation of track star Hiroshi Kasahara and the financial support of political activist Yang Chao-chia (楊肇嘉), Chang headed to Japan in 1931 to undergo formal training at Waseda University. He started with the triple jump, but later switched to sprinting and hurdles, which he excelled at.

In May 1932, he participated in the Summer Olympics tryouts for the 400m dash, finishing fourth at 50.4 seconds. He learned the news of his selection from a newspaper the next day, and he was overjoyed — he had finally achieved his goal.

“I knocked the socks off of those discriminatory Japanese living in Taiwan: A Taiwanese is representing Japan!” he writes.

It was a 17-day journey to Los Angeles by boat. They were greeted by scores of Japanese-Americans, and when he gave autographs to his supporters, Chang always added “Taiwan” at the end so they knew where he came from. Many were curious about the colony and asked him to tell them about it. No Taiwanese supporters turned up.

Chang was disappointed in his performance, vowing to try again four years later. He continued to see domestic success, however, setting national records for the 400-meter sprint and 800-meter relay at the Meiji Shrine Games. He also qualified for the Far Eastern Championship Games, but was forced to sit out due to injury.

DEDICATED TO SPORTS

Chang graduated in 1935 and headed to Japanese-occupied Manchukuo (today’s northeast China) to work for the railroad there.

He continued to train and compete. One notable event was a tournament held in Taiwan between Japan’s three overseas territories of Manchukuo, Korea and Taiwan. Chang had mixed feelings competing against his own countrymen as a member of the Manchukuo team, but they dominated the field.

In 1936, Chang headed to Berlin for the Summer Olympics. However he failed to place again. That would be his final Olympics appearance, as the 1940 and 1944 games were canceled due to World War II. During the war, he worked in Japanese-occupied Beijing.

Chang returned home in 1946. He served on the board of the Taiwan Provincial Sports Association and participated in the first Provincial Games. Despite being 36, he still claimed gold in the triple jump, decathlon and 400m relay.

In 1948, Chang headed to Shanghai for the National Games as the captain of Team Taiwan, which won the track and field championship. He fell seriously ill afterward, and decided to retire.

Chang continued to promote sports in Taiwan and served as a coach and referee, leading local teams to matches in the Philippines and Japan. His disciples include Chen Ying-lang (陳英郎), the first Taiwanese to represent the Republic of China at the Olympics, and Yang Chuan-kwang (楊傳廣, Amis name Maysang Kalimud), the first Taiwanese to win an Olympic medal.

His biggest disappointment was not being sent to the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo — many believed that he would be the ideal candidate as he was familiar with Japan’s track scene and knew all the bigwigs, but the authorities said they wanted to give a chance to younger coaches.

“Due to changing times and his extraordinary career as an athlete, he had to face complicated identity issues for his entire life,” Lin writes.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,