What Hillary Clinton lost was her chance to be the first female US president; what she has gained in the eight years since that wrenching disappointment is less clear.

“My life is richer and my spirit is stronger,” she insists, but her new book, Something Lost, Something Gained: Reflections on Life, Love and Liberty, reveals her to be also the victim of lingering PTSD.

Brooding about her defeat, she muddles the five-step grieving process and alternates between denial and anger, bargaining and depression. As yet, despite walks in the woods and romps with her grandchildren, she seems not to have arrived at acceptance. Just as Donald Trump continues to grouse about the supposedly stolen election of 2020, so Clinton shadow-boxes her way through endless reruns of her wonky, uncharismatic 2016 campaign.

An FBI official, she relates, recently commiserated with her about Trump’s victory and blamed the bureau for tripping up her candidacy when it reopened an investigation into her e-mails. Clinton spurns his offer of sympathy, snapping

“I would have been a great president,” and stalks away.

Later, she elaborates a morbid fantasy about the US in Trump’s second term, with troops in the streets and concentration camps for refugees. In 2016, Trump anatomized American malaise and boasted: “I alone can fix it.”

Clinton’s doomy scenario has a corresponding unspoken subtext. “I alone,” she seems to imply, “could have stopped him.”

ENTITLED

Her sense of entitlement leads her to experiment with appropriate titles for herself, if only the outcome had been different. In the 19th century, the first lady was sometimes called the lady presidentress, which for Clinton has a certain antique allure. She also wonders whether she could have got away with calling herself President Rodham Clinton, in deference to her parents, and to differentiate herself from her husband.

Deprived of power, she has had to settle for fame, and she moves in a blinding glare of publicity. When she teaches at Columbia University, her students are allowed five minutes in which to photograph her before the class begins.

Her buddy Steven Spielberg advises her about pitching a movie idea in Hollywood; she goes to Broadway plays — where she once “got two standing ovations just for showing up!” — with her bosom chum Anna Wintour.

Canoeing in rural Georgia, she just happens to be accompanied “by a small film crew.” At her most grandiose, she is something of a mythomaniac. She rails at an “alt-right” Web site that depicts Trump as Perseus and Clinton as the beheaded Medusa, but reveals that as a girl she modeled herself on Greek prototypes such as “Athena, the goddess of wisdom and war, and Artemis, the goddess of the hunt,” even asking her mother “if I could get a bow and arrow.”

Would that have equipped her to puncture the puffed-up Trump?

Clinton’s publisher, she says, wanted a volume of table talk; instead, she delivered a series of op-eds on universal day care, abortion law and her other “passion projects.” Informality does not come naturally to a woman who feels “the weight of civic responsibility” and even patriotically color codes her clothes for her “symbolic moments.”

INSTITUTIONALIZED

Those pressures have institutionalized her: she is as uptight as the Statue of Liberty. A section on her marriage briefly mentions Bill Clinton’s impeachment while saying nothing about the sexual lapses that provoked it. Perhaps she gives more away when she lightheartedly remembers Bill making “plans for his someday funeral.”

But then she astonishingly remarks that she feels “a lot of guilt about what my run for president did to Bill:” is she deflecting her own pain or injecting it into him?

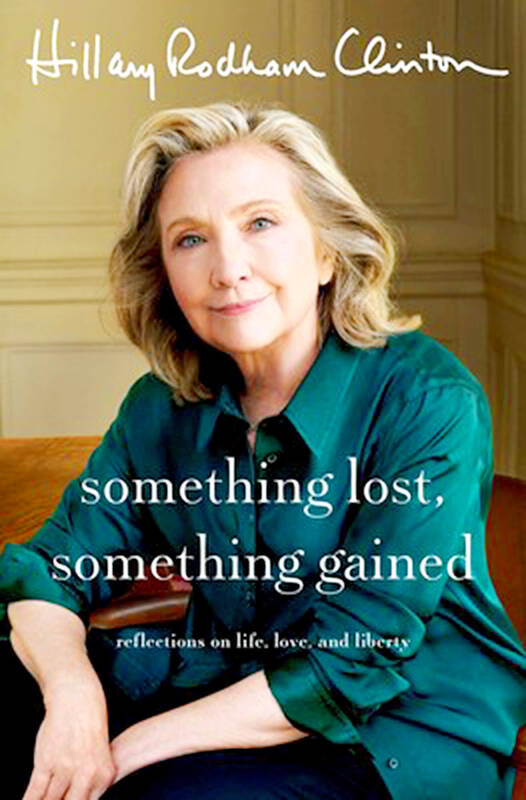

Dreaming about a coronation rather than an inauguration, she watches the 80-year-old Joni Mitchell at an awards ceremony regally “holding court from an armchair that looked like a golden throne,” with her cane as a scepter. This may be Clinton’s preferred persona: on the book’s cover, an unrecognizable photograph by Annie Leibovitz, another BFF, portrays her as an extravagantly maned lion queen.

Here, as always, Clinton retreats into official inscrutability, showing the world a sober and strictly public face.

“I take no pleasure in being right,” she says when Trump is convicted of 34 felonies.

Couldn’t she have allowed herself just a small illicit thrill of schadenfreude?

Clinton, now 76, concludes by anticipating another decade of strenuous activism. She feels “a responsibility for building the future;” meanwhile, however, she is receding into the past.

When she says: “I flew on Air Force One, dined with kings and queens and was constantly surrounded by armed guards,” she sounds like a soliloquist in a nursing home, ruefully revisiting her glory days while her fellow residents nod off. Whether in politics or not, as we age we are all monarchs nudged into abdication, or presidents arriving at the end of their allotted term. It’s a melancholy fate, but better, I suppose, than being binned like a limp lettuce after its sell-by date.

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and the country’s other political groups dare not offend religious groups, says Chen Lih-ming (陳立民), founder of the Taiwan Anti-Religion Alliance (台灣反宗教者聯盟). “It’s the same in other democracies, of course, but because political struggles in Taiwan are extraordinarily fierce, you’ll see candidates visiting several temples each day ahead of elections. That adds impetus to religion here,” says the retired college lecturer. In Japan’s most recent election, the Liberal Democratic Party lost many votes because of its ties to the Unification Church (“the Moonies”). Chen contrasts the progress made by anti-religion movements in

Taiwan doesn’t have a lot of railways, but its network has plenty of history. The government-owned entity that last year became the Taiwan Railway Corp (TRC) has been operating trains since 1891. During the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, the colonial government made huge investments in rail infrastructure. The northern port city of Keelung was connected to Kaohsiung in the south. New lines appeared in Pingtung, Yilan and the Hualien-Taitung region. Railway enthusiasts exploring Taiwan will find plenty to amuse themselves. Taipei will soon gain its second rail-themed museum. Elsewhere there’s a number of endearing branch lines and rolling-stock collections, some

Last week the State Department made several small changes to its Web information on Taiwan. First, it removed a statement saying that the US “does not support Taiwan independence.” The current statement now reads: “We oppose any unilateral changes to the status quo from either side. We expect cross-strait differences to be resolved by peaceful means, free from coercion, in a manner acceptable to the people on both sides of the Strait.” In 2022 the administration of Joe Biden also removed that verbiage, but after a month of pressure from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), reinstated it. The American

This was not supposed to be an election year. The local media is billing it as the “2025 great recall era” (2025大罷免時代) or the “2025 great recall wave” (2025大罷免潮), with many now just shortening it to “great recall.” As of this writing the number of campaigns that have submitted the requisite one percent of eligible voters signatures in legislative districts is 51 — 35 targeting Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus lawmakers and 16 targeting Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers. The pan-green side has more as they started earlier. Many recall campaigns are billing themselves as “Winter Bluebirds” after the “Bluebird Action”