Sept. 23 to Sept. 29

The construction of the Babao Irrigation Canal (八堡圳) was not going well. Large-scale irrigation structures were almost unheard of in Taiwan in 1709, but Shih Shih-pang (施世榜) was determined to divert water from the Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) to the Changhua plain, where he owned land, to promote wet rice cultivation.

According to legend, a mysterious old man only known as Mr. Lin (林先生) appeared and taught Shih how to use woven conical baskets filled with rocks called shigou (石笱) to control water diversion, as well as other techniques such as surveying terrain by observing shadows during nighttime. It worked, and upon the canal’s completion in 1719, Shih prepared a substantial reward for Mr. Lin. However, the old man turned down the money and was never heard from again.

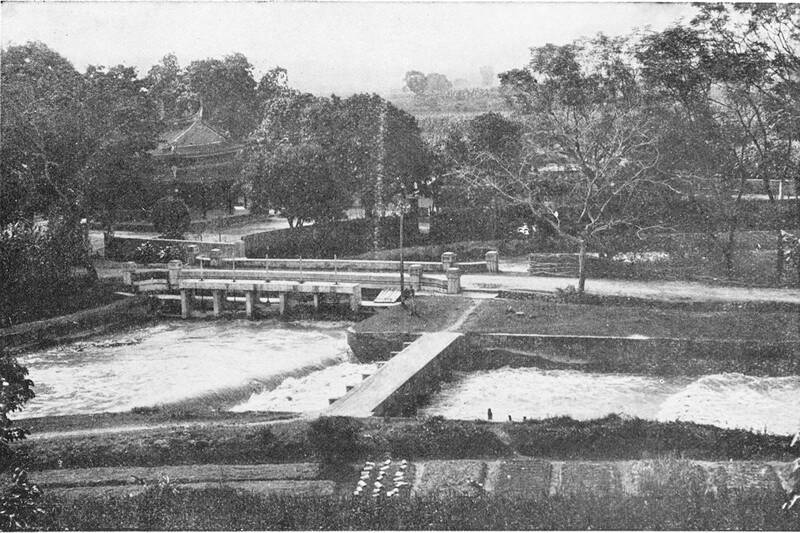

Photo courtesy of Ershuei Township Office

Located in today’s Ershuei Township (二水), the Babao Canal is among the oldest of its kind in Taiwan. It turned the Changhua plain into Taiwan’s top granary, much of the rice being exported to China, which was experiencing a population explosion. The canal contributed to the rise of Lukang (鹿港) as Taiwan’s second most prosperous city after Tainan. Shih spent his later years in Lukang, and his spirit tablet is worshiped in the town’s famous Tianhou Temple (天后宮).

The locals of Ershuei also never forgot about Mr. Lin. At some point, they built the Mr. Lin Temple (林先生廟) at the source of the canal. Shih is also honored there, as well as Huang Shih-ching (黃仕卿), who built the nearby Shiwujhuang Canal (十五庄圳), which the Japanese later renamed the Babao Second Canal and administered them under one system.

Both canals remained earthen structures until they were fortified with reinforced concrete in the 1960s. They are currently undergoing a second reinforcement process due to cracks and leaks in the concrete, with the latest phase completed last week.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

RISE OF THE SHIH CLAN

Although the Qing Dynasty could not stem the migration of Han people to Taiwan during the 1700s, prospectors still had to obtain an official permit to claim “uncultivated” land outside of the delineated indigenous territory, writes Liou Yue-chia (劉育嘉) in The Development of Changhua County in the Qing Dynasty, 1723-1887 (清代彰化縣的開發). These permits often went to influential families, who then invited tenant farmers to till the land.

In central Taiwan, most permit holders were government officials or gentry. This included Shih Shih-pang, who was a distant relative of Shih Lang (施琅), the Qing admiral who destroyed the Tainan-based Kingdom of Tungning (東寧) in 1683 and convinced the emperor to annex Taiwan. Shih Lang made a fortune in Taiwan afterwards through what many believe to be questionable means, and he made sure that his extended family benefited, Liou writes.

Photo courtesy of National Changhua Life Arts Center

Shih Shih-pang’s father Shih Ping (施秉) participated in Shih Lang’s invasion of Taiwan, and was bestowed with an official title due to the campaign’s success. Through the family’s connections he became a successful sugar exporter in his hometown of Quanzhou, Fujian Province, and further increased his wealth through real estate, writes Huang Fu-san (黃富三) in Pioneer of Taiwan’s Wet Farming Expansion: A Family History of Shih Shih-pang (臺灣水田化運動先驅:施世榜家族史).

It’s unclear why the thriving Shih Ping had to leave for Taiwan, but Huang suggests that the government forcefully relocated him due to a local dispute he was involved in. Taiwan was a major sugar producer and Shih Ping was familiar with the industry, and with the backing of the Shih Lang, it probably wasn’t too risky of a move.

He and his family made the journey in 1693, settling in Kaohsiung’s Fengshan District (鳳山). At that time, Shih Shih-pang was 22 years old. The younger Shih officially established residence in Fengshan and passed the local imperial examinations.

Photo courtesy of Academia Sinica

ARDUOUS ENDEAVOR

The family continued with the sugar trade and about a decade later, they began investing in rice production in central Taiwan. It was a smart business move, since by this time, rice was replacing sugar as Taiwan’s most lucrative export.

The previous indigenous Babuza and Hoanya inhabitants engaged in shifting subsistence agriculture, which the Han arrivals emulated at first, writes Shih Jui-pin (石瑞彬) for the Taiwan Historica E-paper. As the settler population grew and the demand from China increased, many began switching to higher-yield wet paddy cultivation, at first with the use of irrigation ponds. But due to the lack of stable water sources across the plain, this method was not suitable for large-scale production.

The creation of a substantial irrigation canal would be costly and time consuming, but Shih Shih-pang believed it was worth it. Construction began in 1709 and took 10 years to complete, drawing water from the Jhuoshuei River and serving more than 19,000 hectares of land. It was named the Shih Family Canal (施厝圳), but by the 1800s it was more commonly referred to as the Babao Canal, in reference to the eight bao (堡, a Qing-era settlement unit) it passed through.

Not much is known of this Mr. Lin, and there’s doubt that he ever existed. The stories say that he was a refined man dressed in modest clothing, roaming the area drinking alcohol and composing poetry. Some believe that he was a water engineer under the Kingdom of Tungning who refused to work for the Qing, choosing to become a hermit instead.

Nearby landowners followed suit, building the Shiwujhuang Canal and Erba Canal (2八圳) in 1721. Shih later invested in the smaller Fuma Canal (福馬圳), which connected the system with the Dadu River (大肚溪) to the north.

CANAL MANAGEMENT

The construction of the canal was just the beginning, however, as it was another costly and taxing task to manage and maintain it.

The Shih family had to make sure that the canal was working at all times, making repairs whenever necessary, and also dealt with natural disasters and conflicts between farmers regarding water usage, Liou writes.

At this point, the Shihs were possibly the richest in Taiwan, writes Huang. Shih Shih-pang and his younger brother participated in the suppression of “Duck King” Chu Yi-kuei’s (朱一貴) rebellion in 1721, and afterward helped with clearing out the remaining rebels and the rebuilding effort.

Shih was rewarded with an official position for his achievements, eventually rising to vice-commander of the local military ward. As gentry, he did his part in contributing to Fengshan, Tainan, Changhua and his hometown in Quanzhou, funding schools, temples, bridges and other facilities. Huang writes that his main cause was promoting education. He was also a poet and writer, penning a compilation of indigenous customs in Pingtung.

The Shih family continued running the Babao and Fuma canals for more than a century. But while Shih Shih-pang’s descendants were active as scholars and officials and inherited his philanthropic spirit, they were not good at business. The family was not able to hold on to its wealth, sharply declining after the 1840s and losing much of their property.

In 1897, canal ownership was transferred to Lukang’s Koo Hsien-jung (辜顯榮), who enjoyed close ties with the Japanese government. Koo continued to run the canal after it became government property in 1905.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the