Despite her well-paying tech job, Li Daijing didn’t hesitate when her cousin asked for help running a restaurant in Mexico City. She packed up and left China for the Mexican capital last year, with dreams of a new adventure.

The 30-year-old woman from Chengdu, the Sichuan provincial capital, hopes one day to start an online business importing furniture from her home country.

“I want more,” Li said. “I want to be a strong woman. I want independence.”

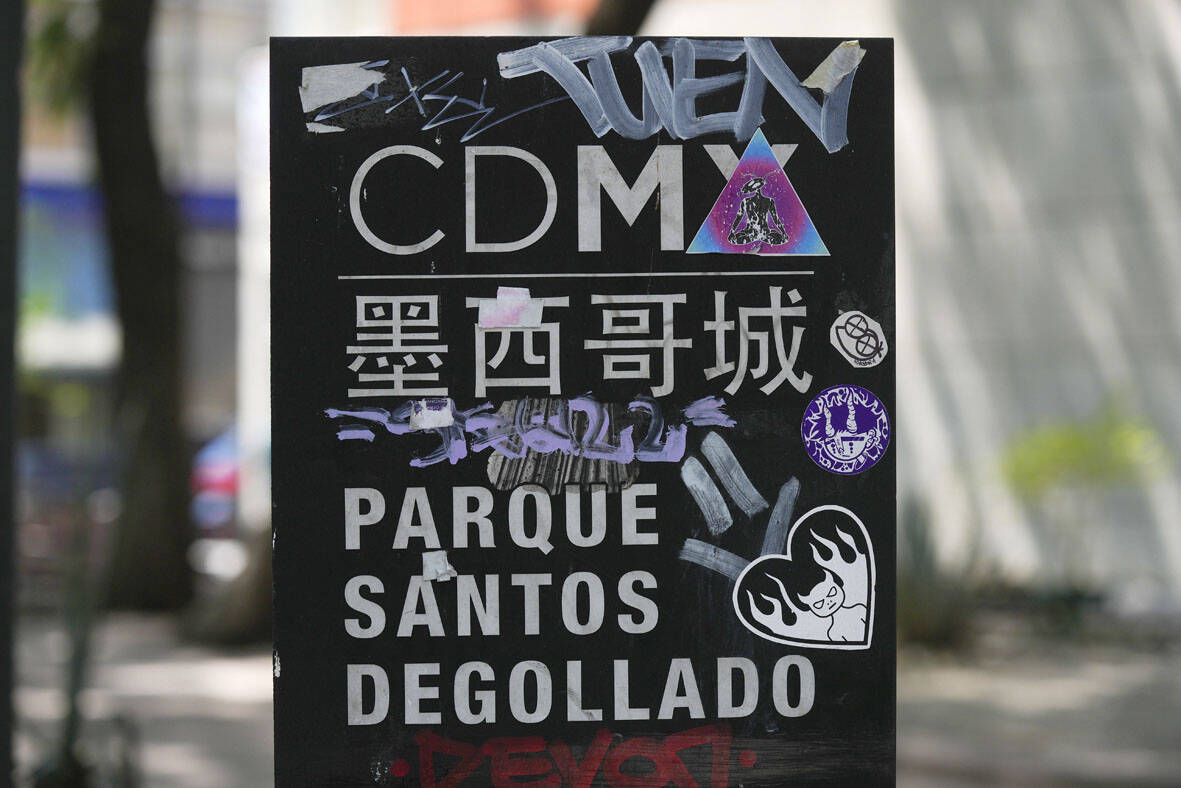

Photo: AP

Li is among a new wave of Chinese migrants who are leaving their country in search of opportunities, more freedom or better financial prospects at a time when China’s economy has slowed, youth unemployment rates remain high and its relations with the US and its allies have soured.

While the US border patrol arrested tens of thousands of Chinese at the US-Mexico border over the past year, thousands are making the Latin American country their final destination. Many have hopes to start businesses of their own, taking advantage of Mexico’s proximity to the US.

Last year, Mexico’s government issued 5,070 temporary residency visas to Chinese immigrants, twice as many as the previous year — making China third, behind the US and Colombia, as the source of migrants granted the permits.

Photo: AP

DEEP ROOTED DIASPORA

A deep-rooted diaspora that has fostered strong family and business networks over decades makes Mexico appealing for new Chinese arrivals; so does a growing presence of Chinese multinationals in Mexico, which have set up shop to be close to markets in the Americas.

“A lot of Chinese started coming here two years ago — and these people need to eat,” said Duan Fan, owner of Nueve y media, a restaurant in Mexico City’s stylish Roma Sur neighborhood that serves the spicy food of Sichuan, his home province.

Photo: AP

“I opened a Chinese restaurant so that people can come here and eat like they do at home,” he said.

Duan, 27, arrived in Mexico in 2017 to work with an uncle who owns a wholesale business in Tepito, near the capital’s historic center, and was later joined by his parents.

Unlike earlier generations of Chinese who came to northern Mexico from the southern Chinese province of Guangdong, the new arrivals are more likely to come from all over China.

Data from the latest 2020 census by Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography show that Chinese immigrants are mainly concentrated in Mexico City. A decade ago, the census recorded the largest concentration of Chinese in the northernmost state of Baja California, on the US-Mexico border across from California.

The arrival of Chinese multinationals is leading an influx of “people from eastern China, more educated and with a broader global background,” said Andrei Guerrero, academic coordinator of the Center for China-Baja California Studies.

In a middle-class Mexico City neighborhood, Viaducto-Piedad, near the city’s historic Chinatown, a new Chinese community has been growing since the late 1990s. Chinese immigrants have not only opened businesses, but have created community spaces for religious events and children’s recreation.

Viaducto-Piedad is recognized by the Chinese themselves as Mexico City’s true “Chinatown,” said Monica Cinco, a specialist in Chinese migration and general director of the EDUCA Mexico Foundation.

“When I asked them why, they would tell me because we live here. We have stores for Chinese consumption, beauty shops and restaurants just for Chinese,” she said. “They live there, there is a community and several public schools in the area have a significant Chinese population.”

SEARCHING FOR FREEDOM

In downtown Mexico City, Chinese entrepreneurs have not only opened new wholesale stores but have also taken over dozens of buildings. At times, they have become a source of tension with local businesses and residents, who say the expansion of Chinese-owned enterprises is displacing them.

At a mini-market in a bustling downtown neighborhood selling Chinese products such as dried wood ear mushrooms and vacuum-packed spicy duck wings, 33-year-old Dong Shengli said he moved to Mexico City from Beijing a few months ago to help manage the shop for some friends.

Dong — who has since found a job with a wholesaler importing knockoff designer sneakers and clothing — said he had worked at China’s National Energy Commission, but was persuaded by his friends to come here.

He plans to explore business possibilities in Mexico, but China still has a pull for him. “My wife and my parents are in China. My mother is elderly, she needs me,” he said.

Others are leaving China in search of greater freedoms. That’s the case for 50-year-old Tan, who gave only his surname out of concern for the safety of his family, who remain in China. He arrived in Mexico this year from the southern province of Guangdong and got a job for a few months at a Sam’s Club. Back home, he got by doing various jobs, including at a chemical plant and writing magazine articles during the pandemic.

But he chafed under what he described as a repressive atmosphere in China.

“It’s not just the oppression in the workplace, it’s the mentality,” he said. “I can feel the political regression, the retreat of freedom and democracy. The implications of that truly make people feel twisted and sick. So, life is very painful.”

What caught his attention in Mexico City were the protests that often pack the city’s main avenues — proof, he said, that the freedom of expression he longs for exists in this country.

LAND OF OPPORTUNITY

At the restaurant where she still helps out in the trendy Juarez neighborhood, Li said Mexico stands out as a land of opportunity for her and other Chinese who don’t have relatives in the US to help them settle there. She said she left China partly because of the competitive workplace culture and high home prices.

“In China, everyone saves money to buy a house, but it’s really expensive to get one,” she said.

Self-confident with a contagious smile, Li said she’s hopeful her skills working as a sales promoter for Chinese tech giant Tencent Games will help her get ahead in Mexico.

She says she has not met many Chinese women like herself in Mexico City: newcomers, young and single.

Most are married and are moving to Mexico to reunite with their husbands. “To come here is to face something unknown,” she said.

Li doesn’t know when she’ll be able to carry out her ambitious business plans, but she has ideas: For example, she imagines that in Henan province she could get chairs, tables and other furniture at a good price. Meanwhile, she is selling furniture imported to Mexico by a Chinese friend on the E-commerce platform Mercado Libre.

“I’m not married, I don’t have a boyfriend, it’s just myself,” she said, “so I’ll work hard and struggle.”

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has